Sorry, we are not able to source the book you are looking for right now.

We did a search for other books with a similar title, however there were no matches. You can try selecting from a similar category, click on the author's name, or use the search box above to find your book.

There was hardly any comfort in playing her private game, because like so many things in Carrie's life, it was sinful. Or so her mother said. Carrie could make things move--by concentrating on them, by willing them to move. Small things, like marbles, would start dancing. Or a candle would fall. A door would lock. This was her game, her power, her sin, firmly repressed like everything else about Carrie.

One act of kindness, as spontaneous as the vicious jokes of her classmates, offered Carrie a new look at herself the fateful night of her senior prom. But another act--of furious cruelty--forever changed things and turned her clandestine game in to a weapon of horror and destruction.

She made a lighted candle fall, and she locked the doors...

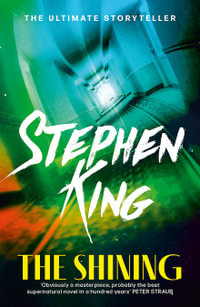

About the Author

Few authors have tapped into our secret fears as adeptly as Stephen King, Master of the Macabre and one of the most widely read novelists writing today. With his trademark blend of fantasy, horror, and psychological suspense, this prolific and immensely popular contemporary writer continues to remind us that evil is still a potent force in the world.

Industry Reviews

News item from the Westover (Me.) weekly Enterprise, August 19, 1966:

RAIN OF STONES REPORTED

It was reliably reported by several persons that a rain of stones fell from a clear blue sky on Carlin Street in the town of Chamberlain on August 17th. The stones fell principally on the home of Mrs. Margaret White, damaging the roof extensively and ruining two gutters and a downspout valued at approximately $25. Mrs. White, a widow, lives with her three-year-old daughter, Carietta.

Mrs. White could not be reached for comment.

Nobody was really surprised when it happened, not really, not at the subconscious level where savage things grow. On the surface, all the girls in the shower room were shocked, thrilled, ashamed, or simply glad that the White bitch had taken it in the mouth again. Some of them might also have claimed surprise, but of course their claim was untrue. Carrie had been going to school with some of them since the first grade, and this had been building since that time, building slowly and immutably, in accordance with all the laws that govern human nature, building with all the steadiness of a chain reaction approaching critical mass.

What none of them knew, of course, was that Carrie White was telekinetic.

Graffiti scratched on a desk of the Barker Street Grammar School in Chamberlain:

Carrie White eats shit.

The locker room was filled with shouts, echoes, and the subterranean sound of showers splashing on tile. The girls had been playing volleyball in Period One, and their morning sweat was light and eager.

Girls stretched and writhed under thehot water, squalling, flicking water, squirting white bars of soap from hand to hand. Carrie stood among them stolidly, a frog among swans. She was a chunky girl with pimples on her neck and back and buttocks, her wet hair completely without color. It rested against her face with dispirited sogginess and she simply stood, head slightly bent, letting the water splat against her flesh and roll off. She looked the part of the sacrificial goat, the constant butt, believer in left-handed monkey wrenches, perpetual foul-up, and she was. She wished forlornly and constantly that Ewen High had individual — and thus private — showers, like the high schools at Westover or Lewiston. They stared. They always stared.

Showers turning off one by one, girls stepping out, removing pastel bathing caps, toweling, spraying deodorant, checking the clock over the door. Bras were hooked, underpants stepped into. Steam hung in the air; the place might have been an Egyptian bathhouse except for the constant rumble of the Jacuzzi whirlpool in the corner. Calls and catcalls rebounded with all the snap and flicker of billiard balls after a hard break.

" — so Tommy said he hated it on me and I — "

" — I'm going with my sister and her husband. He picks his nose but so does she, so they're very — "

" — shower after school and — "

" — too cheap to spend a goddam penny so Cindi and I — "

Miss Desjardin, their slim, nonbreasted gym teacher, stepped in, craned her neck around briefly, and slapped her hands together once, smartly. "What are you waiting for, Carrie? Doom? Bell in five minutes." Her shorts were blinding white, her legs not too curved but striking in their unobtrusive muscularity. A silver whistle, won in college archery competition, hung around her neck.

The girls giggled and Carrie looked up, her eyes slow and dazed from the heat and the steady, pounding roar of the water. "Ohuh?"

It was a strangely froggy sound, grotesquely apt, and the girls giggled again. Sue Snell had whipped a towel from her hair with the speed of a magician embarking on a wondrous feat and began to comb rapidly. Miss Desjardin made an irritated cranking gesture at Carrie and stepped out.

Carrie turned off the shower. It died in a drip and a gurgle.

It wasn't until she stepped out that they all saw the blood running down her leg.

From The Shadow Exploded: Documented Facts and Specific Conclusions Derived from the Case of Carietta White, by David R. Congress (Tulane University Press: 1981), p. 34:

It can hardly be disputed that failure to note specific instances of telekinesis during the White girl's earlier years must be attributed to the conclusion offered by White and Stearns in their paper Telekinesis: A Wild Talent Revisited — that the ability to move objects by effort of the will alone comes to the fore only in moments of extreme personal stress. The talent is well hidden indeed; how else could it have remained submerged for centuries with only the tip of the iceberg showing above a sea of quackery?

We have only skimpy hearsay evidence upon which to lay our foundation in this case, but even this is enough to indicate that a "TK" potential of immense magnitude existed within Carrie White. The great tragedy is that we are now all Monday-morning quarterbacks...

"Per-iod!"

The catcall came first from Chris Hargensen. It struck the tiled walls, rebounded, and struck again. Sue Snell gasped laughter from her nose and felt an odd, vexing mixture of hate, revulsion, exasperation, and pity. She just looked so dumb, standing there, not knowing what was going on. God, you'd think she never —

"PER-iod!"

It was becoming a chant, an incantation. Someone in the background (perhaps Hargensen again, Sue couldn't tell in the jungle of echoes) was yelling, "Plug it up!" with hoarse, uninhibited abandon.

"PER-iod, PER-iod, PER-iod!"

Carrie stood dumbly in the center of a forming circle, water rolling from her skin in beads. She stood like a patient ox, aware that the joke was on her (as always), dumbly embarrassed but unsurprised.

Sue felt welling disgust as the first dark drops of menstrual blood struck the tile in dime-sized drops. "For God's sake, Carrie, you got your period!" she cried. "Clean yourself up!"

"Ohuh?"

She looked around bovinely. Her hair stuck to her cheeks in a curving helmet shape. There was a cluster of acne on one shoulder. At sixteen, the elusive stamp of hurt was already marked clearly in her eyes.

"She thinks they're for lipstick!" Ruth Gogan suddenly shouted with cryptic glee, and then burst into a shriek of laughter. Sue remembered the comment later and fitted it into a general picture, but now it was only another senseless sound in the confusion. Sixteen? She was thinking. She must know what's happening, she —

More droplets of blood. Carrie still blinked around at her classmates in slow bewilderment.

Helen Shyres turned around and made mock throwing-up gestures.

"You're bleeding!" Sue yelled suddenly, furiously. "You're bleeding, you big dumb pudding!"

Carie looked down at herself.

She shrieked.

The sound was very loud in the humid locker room.

A tampon suddenly struck her in the chest and fell with a plop at her feet. A red flower stained the absorbent cotton and spread.

Then the laughter, disgusted, contemptuous, horrified, seemed to rise and bloom into something jagged and ugly, and the girls were bombarding her with tampons and sanitary napkins, some from purses, some from the broken dispenser on the wall. They flew like snow and the chant became: "Plug it up, plug it up, plug it up, plug it — "

Sue was throwing them too, throwing and chanting with the rest, not really sure what she was doing — a charm had occurred to her mind and it glowed there like neon: There's no harm in it really no harm in it really no harm — It was still flashing and glowing, reassuringly, when Carrie suddenly began to howl and back away, flailing her arms and grunting and gobbling.

The girls stopped, realizing that fission and explosion had finally been reached. It was at this point, when looking back, that some of them would claim surprise. Yet there had been all these years, all these years of let's short-sheet Carrie's bed at Christian Youth Camp and I found this love letter from Carrie to Flash Bobby Pickett let's copy it and pass it around and hide her underpants somewhere and put this snake in her shoe and duck her again, duck her again; Carrie tagging along stubbornly on biking trips, known one year as pudd'n and the next year as truck-face, always smelling sweaty, not able to catch up; catching poison ivy from urinating in the bushes and everyone finding out (hey, scratch-ass, your bum itch?); Billy Preston putting peanut butter in her hair that time she fell asleep in study hall; the pinches, the legs outstretched in school aisles to trip her up, the books knocked from her desk, the obscene postcard tucked into her purse; Carrie on the church picnic and kneeling down clumsily to pray and the seam of her old madras skirt splitting along the zipper like the sound of a huge wind-breakage; Carrie always missing the ball, even in kickball, falling on her face in Modern Dance during their sophomore year and chipping a tooth, running into the net during volleyball; wearing stockings that were always run, running, or about to run, always showing sweat stains under the arms of her blouses; even the time Chris Hargensen called up after school from the Kelly Fruit Company downtown and asked her if she knew that pig poop was spelled C-A-R-R-I-E: Suddenly all this and the critical mass was reached. The ultimate shit-on, gross-out, put-down, long searched for, was found. Fission.

She backed away, howling in the new silence, fat forearms crossing her face, a tampon stuck in the middle of her pubic hair.

The girls watched her, their eyes shining solemnly.

Carrie backed into the side of one of the four large shower compartments and slowly collapsed into a sitting position. Slow, helpless groans jerked out of her. Her eyes rolled with wet whiteness, like the eyes of a hog in the slaughtering pen.

Sue said slowly, hesitantly: "I think this must be the first time she ever — "

That was when the door pumped open with a flat and hurried bang and Miss Desjardin burst in to see what the matter was.

From The Shadow Exploded (p. 41):

Both medical and psychological writers on the subject are in agreement that Carrie White's exceptionally late and traumatic commencement of the menstrual cycle might well have provided the trigger for her latent talent.

It seems incredible that, as late as 1979, Carrie knew nothing of the mature woman's monthly cycle. It is nearly as incredible to believe that the girl's mother would permit her daughter to reach the age of nearly seventeen without consulting a gynecologist concerning the daughter's failure to menstruate.

Yet the facts are incontrovertible. When Carrie White realized she was bleeding from the vaginal opening, she had no idea of what was taking place. She was innocent of the entire concept of menstruation.

One of her surviving classmates, Ruth Gogan, tells of entering the girls' locker room at Ewen High School the year before the events we are concerned with and seeing Carrie using a tampon to blot her lipstick with. At that time Miss Gogan said: "What the hell are you up to?" Miss White replied: "Isn't this right?" Miss Gogan then replied: "Sure. Sure it is." Ruth Gogan let a number of her girl friends in on this (she later told this interviewer she thought it was "sorta cute"), and if anyone tried in the future to inform Carrie of the true purpose of what she was using to make up with, she apparently dismissed the explanation as an attempt to pull her leg. This was a facet of her life that she had become exceedingly wary of...

When the girls were gone to their Period Two classes and the bell had been silenced (several of them had slipped quietly out the back door before Miss Desjardin could begin to take names), Miss Desjardin employed the standard tactic for hysterics: She slapped Carrie smartly across the face. She hardly would have admitted the pleasure the act gave her, and she certainly would have denied that she regarded Carrie as a fat, whiny bag of lard. A first-year teacher, she still believed that she thought all children were good.

Carrie looked up at her dumbly, face still contorted and working. "M-M-Miss D-D-Des-D — "

"Get up," Miss Desjardin said dispassionately. "Get up and tend to yourself."

"I'm bleeding to death!" Carrie screamed, and one blind, searching hand came up and clutched Miss Desjardin's white shorts. It left a bloody handprint.

"I...you..." The gym teacher's face contorted into a pucker of disgust, and she suddenly hurled Carrie, stumbling, to her feet. "Get over there!"

Carrie stood swaying between the showers and the wall with its dime sanitary-napkin dispenser, slumped over, breasts pointing at the floor, her arms dangling limply. She looked like an ape. Her eyes were shiny and blank.

"Now," Miss Desjardin said with hissing, deadly emphasis, "you take one of those napkins out...no, never mind the coin slot, it's broken anyway...take one and...damn it, will you do it! You act as if you never had a period before."

"Period?" Carrie said.

Her expression of complete unbelief was too genuine, too full of dumb and hopeless horror, to be ignored or denied. A terrible and black foreknowledge grew in Rita Desjardin's mind. It was incredible, could not be. She herself had begun menstruation shortly after her eleventh birthday and had gone to the head of the stairs to yell down excitedly: "Hey, Mum, I'm on the rag!"

"Carrie?" she said now. She advanced toward the girl. "Carrie?"

Carrie flinched away. At the same instant, a rack of softball bats in the corner fell over with a large, echoing bang. They rolled every which way, making Desjardin jump.

"Carrie, is this your first period?"

But now that the thought had been admitted, she hardly had to ask. The blood was dark and flowing with terrible heaviness. Both of Carrie's legs were smeared and splattered with it, as though she had waded through a river of blood.

"It hurts," Carrie groaned. "My stomach..."

"That passes," Miss Desjardin said. Pity and self-shame met in her and mixed uneasily. "You have to...uh, stop the flow of blood. You — "

There was a bright flash overhead, followed by a flashgun-like pop as a lightbulb sizzled and went out. Miss Desjardin cried out with surprise, and it occurred to her

(the whole damn place is falling in)

that this kind of thing always seemed to happen around Carrie when she was upset, as if bad luck dogged her every step. The thought was gone almost as quickly as it had come. She took one of the sanitary napkins from the broken dispenser and unwrapped it.

"Look," she said. "Like this — "

From The Shadow Exploded (p. 54):

Carrie White's mother, Margaret White, gave birth to her daughter on September 21, 1963, under circumstances which can only be termed bizarre. In fact, an overview of the Carrie White case leaves the careful student with one feeling ascendent over all others: that Carrie was the only issue of a family as odd as any that has ever been brought to popular attention.

As noted earlier, Ralph White died in February of 1963 when a steel girder fell out of a carrying sling on a housing-project job in Portland. Mrs. White continued to live alone in their suburban Chamberlain bungalow.

Due to the Whites' near-fanatical fundamentalist religious beliefs, Mrs. White had no friends to see her through her period of bereavement. And when her labor began seven months later, she was alone.

At approximately 1:30 p.m. on September 21, the neighbors on Carlin Street began to hear screams from the White bungalow. The police, however, were not summoned to the scene until after 6:00 p.m. We are left with two unappetizing alternatives to explain this time lag: Either Mrs. White's neighbors on the street did not wish to become involved in a police investigation, or dislike for her had become so strong that they deliberately adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Mrs. Georgia McLaughlin, the only one of three remaining residents who were on the street at that time and who would talk to me, said that she did not call the police because she thought the screams had something to do with "holy rollin'."

When the police did arrive at 6:22 p.m. the screams had become irregular. Mrs. White was found in her bed upstairs, and the investigating officer, Thomas G. Mearton, at first thought she had been the victim of an assault. The bed was drenched with blood, and a butcher knife lay on the floor. It was only then that he saw the baby, still partially wrapped in the placental membrane, at Mrs. White's breast. She had apparently cut the umbilical cord herself with the knife.

It staggers both imagination and belief to advance the hypothesis that Mrs. Margaret White did not know she was pregnant, or even understand what the word entails, and recent scholars such as J. W. Bankson and George Fielding have made a more reasonable case for the hypothesis that the concept, linked irrevocably in her mind with the "sin" of intercourse, had been blocked entirely from her mind. She may simply have refused to believe that such a thing could happen to her.

We have records of at least three letters to a friend in Kenosha, Wisconsin, that seem to prove conclusively that Mrs. White believed, from her fifth month on, that she had "a cancer of the womanly parts" and would soon join her husband in heaven...

When Miss Desjardin led Carrie up to the office fifteen minutes later, the halls were mercifully empty. Classes droned onward behind closed doors.

Carrie's shrieks had finally ended, but she had continued to weep with steady regularity. Desjardin had finally placed the napkin herself, cleaned the girl up with wet paper towels, and gotten her back into her plain cotton underpants.

She tried twice to explain the commonplace reality of menstruation, but Carrie clapped her hands over her ears and continued to cry.

Mr. Morton, the assistant principal, was out of his office in a flash when they entered. Billy deLois and Henry Trennant, two boys waiting for the lecture due them for cutting French I, goggled around from their chairs.

"Come in," Mr. Morton said briskly. "Come right in." He glared over Desjardin's shoulder at the boys, who were staring at the bloody handprint on her shorts. "What are you looking at?"

"Blood," Henry said, and smiled with a kind of vacuous surprise.

"Two detention periods," Morton snapped. He glanced down at the bloody handprint and blinked.

He closed the door behind them and began pawing through the top drawer of his filing cabinet for a school accident form.

"Are you all right, uh — ?"

"Carrie," Desjardin supplied. "Carrie White." Mr. Morton had finally located an accident form. There was a large coffee stain on it. "You won't need that, Mr. Morton."

"I suppose it was the trampoline. We just...I won't?"

"No. But I think Carrie should be allowed to go home for the rest of the day. She's had a rather frightening experience." Her eyes flashed a signal which he caught but could not interpret.

"Yes, okay, if you say so. Good. Fine." Morton crumpled the form back into the filing cabinet, slammed it shut with his thumb in the drawer, and grunted. He whirled gracefully to the door, yanked it open, glared at Billy and Henry, and called: "Miss Fish, could we have a dismissal slip here, please? Carrie Wright."

"White," said Miss Desjardin.

"White," Morton agreed.

Billy deLois sniggered.

"Week's detention!" Morton barked. A blood blister was forming under his thumbnail. Hurt like hell. Carrie's steady, monotonous weeping went on and on.

Miss Fish brought the yellow dismissal slip and Morton scrawled his initials on it with his silver pocket pencil, wincing at the pressure on his wounded thumb.

"Do you need a ride, Cassie?" he asked. "We can call a cab if you need one."

She shook her head. He noticed with distaste that a large bubble of green mucus had formed at one nostril. Morton looked over her head and at Miss Desjardin.

"I'm sure she'll be all right," she said. "Carrie only has to go over to Carlin Street. The fresh air will do her good."

Morton gave the girl the yellow slip. "You can go now, Cassie," he said magnanimously.

"That's not my name!" she screamed suddenly.

Morton recoiled, and Miss Desjardin jumped as if struck from behind. The heavy ceramic ashtray on Morton's desk (it was Rodin's Thinker with his head turned into a receptacle for cigarette butts) suddenly toppled to the rug, as if to take cover from the force of her scream. Butts and flakes of Morton's pipe tobacco scattered on the pale-green nylon rug.

"Now, listen," Morton said, trying to muster sternness. "I know you're upset, but that doesn't mean I'll stand for — "

"Please," Miss Desjardin said quietly.

Morton blinked at her and then nodded curtly. He tried to project the image of a lovable John Wayne figure while performing the disciplinary functions that were his main job as Assistant Principal, but did not succeed very well. The administration (usually represented at Jay Cee suppers, P.T.A. functions, and American Legion award ceremonies by Principal Henry Grayle) usually termed him "lovable Mort." The student body was more apt to term him "that crazy ass-jabber from the office." But, as few students such as Billy deLois and Henry Trennant spoke at P.T.A. functions or town meetings, the administration's view tended to carry the day.

Now lovable Mort, still secretly nursing his jammed thumb, smiled at Carrie and said, "Go along then if you like, Miss Wright. Or would you like to sit a spell and just collect yourself?"

"I'll go," she muttered, and swiped at her hair. She got up, then looked around at Miss Desjardin. Her eyes were wide open and dark with knowledge. "They laughed at me. Threw things. They've always laughed."

Desjardin could only look at her helplessly.

Carrie left.

For a moment there was silence; Morton and Desjardin watched her go. Then, with an awkward throat-clearing sound, Mr. Morton hunkered down carefully and began to sweep together the debris from the fallen ashtray.

"What was that all about?"

She sighed and looked at the drying maroon handprint on her shorts with distaste. "She got her period. Her first period. In the shower."

Morton cleared his throat again and his cheeks went pink. The sheet of paper he was sweeping with moved even faster. "Isn't she a bit, uh — "

"Old for her first? Yes. That's what made it so traumatic for her. Although I can't understand why her mother..." The thought trailed off, forgotten for the moment. "I don't think I handled it very well, Morty, but I didn't understand what was going on. She thought she was bleeding to death."

He stared up sharply.

"I don't believe she knew there was such a thing as menstruation until half an hour ago."

"Hand me that little brush there, Miss Desjardin. Yes, that's it." She handed him a little brush with the legend Chamberlain Hardware and Lumber Company NEVER Brushes You Off written up the handle. He began to brush his pile of ashes onto the paper. "There's still going to be some for the vacuum cleaner, I guess. This deep pile is miserable. I thought I set that ashtray back on the desk further. Funny how things fall over." He bumped his head on the desk and sat up abruptly. "It's hard for me to believe that a girl in this or any other high school could get through three years and still be alien to the fact of menstruation, Miss Desjardin."

"It's even more difficult for me," she said. "But it's all I can think of to explain her reaction. And she's always been a group scapegoat."

"Um." He funneled the ashes and butts into the wastebasket and dusted his hands. "I've placed her, I think. White. Margaret White's daughter. Must be. That makes it a little easier to believe." He sat down behind his desk and smiled apologetically. "There's so many of them. After five years or so, they all start to merge into one group face. You call boys by their brother's names, that type of thing. It's hard."

"Of course it is."

"Wait 'til you've been in the game twenty years, like me," he said morosely, looking down at his blood blister. "You get kids that look familiar and find out you had their daddy the year you started teaching. Margaret White was before my time, for which I am profoundly grateful. She told Mrs. Bicente, God rest her, that the Lord was reserving a special burning seat in hell for her because she gave the kids an outline of Mr. Darwin's beliefs on evolution. She was suspended twice while she was here — once for beating a classmate with her purse. Legend has it that Margaret saw the classmate smoking a cigarette. Peculiar religious views. Very peculiar." His John Wayne expression suddenly snapped down. "The other girls. Did they really laugh at her?"

"Worse. They were yelling and throwing sanitary napkins at her when I walked in. Throwing them like...like peanuts."

"Oh. Oh, dear." John Wayne disappeared. Mr. Morton went scarlet. "You have names?"

"Yes. Not all of them, although some of them may rat on the rest. Christine Hargensen appeared to be the ringleader...as usual."

"Chris and her Mortimer Snerds," Morton murmured.

"Yes. Tina Blake, Rachel Spies, Helen Shyres, Donna Thibodeau and her sister Mary Lila Grace, Jessica Upshaw. And Sue Snell." She frowned. "You wouldn't expect a trick like that from Sue. She's never seemed the type for this kind of a — a stunt."

"Did you talk to the girls involved?"

Miss Desjardin chuckled unhappily. "I got them the hell out of there. I was too flustered. And Carrie was having hysterics."

"Um." He steepled his fingers. "Do you plan to talk to them?"

"Yes." But she sounded reluctant.

"Do I detect a note of — "

"You probably do," she said glumly. "I'm living in a glass house, see. I understand how those girls felt. The whole thing just made me want to take the girl and shake her. Maybe there's some kind of instinct about menstruation that makes women want to snarl, I don't know. I keep seeing Sue Snell and the way she looked."

"Um," Mr. Morton repeated wisely. He did not understand women and had no urge at all to discuss menstruation.

"I'll talk to them tomorrow," she promised, rising. "Rip them down one side and up the other."

"Good. Make the punishment suit the crime. And if you feel you have to send any of them to, ah, to me, feel free — "

"I will," she said kindly. "By the way, a light blew out while I was trying to calm her down. It added the final touch."

"I'll send a janitor right down," he promised. "And thanks for doing your best, Miss Desjardin. Will you have Miss Fish send in Billy and Henry?"

"Certainly." She left.

He leaned back and let the whole business slide out of his mind. When Billy deLois and Henry Trennant, class-cutters extraordinaire, slunk in, he glowered at them happily and prepared to talk tough.

As he often told Hank Grayle, he ate class-cutters for lunch.

Grafitti scratched on a desk in Chamberlain Junior High School: Roses are red, violets are blue, sugar is sweet, but Carrie White eats shit.

She walked down Ewen Avenue and crossed over to Carlin at the stoplight on the corner. Her head was down and she was trying to think of nothing. Cramps came and went in great, gripping waves, making her slow down and speed up like a car with carburetor trouble. She stared at the sidewalk. Quartz glittering in the cement. Hopscotch grids scratched in ghostly, rain-faded chalk. Wads of gum stamped flat. Pieces of tinfoil and penny-candy wrappers. They all hate and they never stop. They never get tired of it. A penny lodged in a crack. She kicked it. Imagine Chris Hargensen all bloody and screaming for mercy. With rats crawling all over her face. Good. Good. That would be good. A dog turd with a foot-track in the middle of it. A roll of blackened caps that some kid had banged with a stone. Cigarette butts. Crash in her head with a rock, with a boulder. Crash in all their heads. Good. Good.

(savior jesus meek and mild)

That was good for Momma, all right for her. She didn't have to go among the wolves every day of every year, out into a carnival of laughers, joke-tellers, pointers, snickerers. And didn't Momma say there would be a Day of Judgment

(the name of that star shall be wormwood and they shall be scourged with scorpions)

and an angel with a sword?

If only it would be today and Jesus coming not with a lamb and a shepherd's crook, but with a boulder in each hand to crush the laughers and the snickerers, to root out the evil and destroy it screaming — a terrible Jesus of blood and righteousness.

And if only she could be His sword and His arm.

She had tried to fit. She had defied Momma in a hundred little ways had tried to erase the redplague circle that had been drawn around her from the first day she had left the controlled environment of the small house on Carlin Street and had walked up to the Barker Street Grammar School with her Bible under her arm. She could still remember that day, the stares, and the sudden, awful silence when she had gotten down on her knees before lunch in the school cafeteria — the laughter had begun on that day and had echoed up through the years.

The redplague circle was like blood itself — you could scrub and scrub and scrub and still it would be there, not erased, not clean. She had never gotten on her knees in a public place again, although she had not told Momma that. Still, the original memory remained, with her and with them. She had fought Momma tooth and nail over the Christian Youth Camp, and had earned the money to go herself by taking in sewing. Momma told her darkly that it was Sin, that it was Methodists and Baptists and Congregationalists and that it was Sin and Backsliding. She forbade Carrie to swim at the camp. Yet although she had swum and had laughed when they ducked her (until she couldn't get her breath any more and they kept doing it and she got panicky and began to scream) and had tried to take part in the camp's activities, a thousand practical jokes had been played on ol' prayin' Carrie and she had come home on the bus a week early, her eyes red and socketed from weeping, to be picked up by Momma at the station, and Momma had told her grimly that she should treasure the memory of her scourging as proof that Momma knew, that Momma was right, that the only hope of safety and salvation was inside the red circle. "For strait is the gate," Momma said grimly in the taxi, and at home she had sent Carrie to the closet for six hours.

Momma had, of course, forbade her to shower with the other girls; Carrie had hidden her shower things in her school locker and had showered anyway, taking part in a naked ritual that was shameful and embarrassing to her in hopes that the circle around her might fade a little, just a little —

(but today o today)

Tommy Erbter, age five, was biking up the other side of the street. He was a small, intense-looking boy on a twenty-inch Schwinn with bright-red training wheels. He was humming "Scoobie Doo, where are you?" under his breath. He saw Carrie, brightened, and stuck out his tongue.

"Hey, ol' fart-face! Ol' prayin' Carrie!"

Carrie glared at him with sudden smoking rage. The bike wobbled on its training wheels and suddenly fell

ISBN: 9780671039721

ISBN-10: 0671039725

Published: 1st November 2002

Format: Paperback

Language: English

Number of Pages: 253

Audience: General Adult

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Country of Publication: US

Dimensions (cm): 18.42 x 10.8 x 1.91

Weight (kg): 0.14

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.

You Can Find This Book In

The Complete Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe - Omnibus Edition

Barnes & Noble Leatherbound Classic Collection

Leather Bound Book

RRP $59.99

$40.90

OFF