In his 1994 A Shorter History of Australia, Geoffrey Blainey confided that for “…many years I have been intermittently writing a very long and multi-sided book about Australia’s history, a book which I might never finish.” Coming from the doyen of Australian historians, this was exciting news. A single-author, inclusive and up-to-date account of our past is long over-due.

Fast-forward over twenty years, and Blainey is still keeping us in suspense. But he has offered us something of what may be to come in The Story of Australia’s People: The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia.

Fast-forward over twenty years, and Blainey is still keeping us in suspense. But he has offered us something of what may be to come in The Story of Australia’s People: The Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia.

This work consists of revised versions of two of Blainey’s earlier books, Triumph of the Nomads, an account of Aboriginal Australia first published in 1975, and A Land Half Won, a history of European Australia up to 1850 first published in 1980. Blainey has updated these earlier works to accommodate several decades of new discoveries and scholarship.

He begins with one of the greatest, but least appreciated achievements of our species: how the Aborigines adapted to dramatic environmental change.

When they first arrived some 60,000 years ago, much of Australia was temperate. At Lake Mungo, for example, the landscape was covered in woodland and the lakes were full, providing the local people with a varied diet. But when the most recent ice age peaked about 20,000 to 18,000 years ago, the woodland began to die off and the lakes dried up. Within about 10,000 to 8000 years, it was a desert.

Blainey catalogues the impact of these changes on Aboriginal society. He dwells, for example, at length on infanticide and abortion as means of population control. How the Aborigines managed to survive these episodes of radical climate change have profound implications for us. Blainey does not engage directly with theories concerning the wider impact of population growth. Yet the experiences of the Aborigines appear to support Ester Boserup’s model of population and economic growth. It holds that the pressure exerted by a growing population on available resources is the spark that ignites technological development and economic change.

That the Aborigines managed to continue supporting themselves through hunting, gathering, burning off and gardening over such a long period raises important social and economic questions. Did they consciously reject technological development? Put another way, did they believe the land provided them with enough and so they consciously spared it from further exploitation ? If so, what does this suggest about likely result of continuing on with the exploitative, destructive impacts of capitalism on the environment here ?

This question is raised by Blainey’s account of the early settlement of Sydney. After briefly rehearsing the well-worn arguments for why Britain established a colony here, Blainey poses perhaps a more fundamental question: why did Britain not abandon the colony when it was conspicuously failing ?

The Europeans who arrived on the First Fleet had no idea how to find or grow food in the new colony. By 1790, the stores they brought with them had begun to run out and they faced starvation. The arrival of the Second Fleet averted this. So the answer to Blainey’s question may be good luck rather than good management. But the key lesson was over-looked. Instead of learning from the Aborigines how to adapt to their new land, the Europeans sought to exploit it by imposing their own system of agriculture, clearing its forests and polluting its waterways – even the famous Tank Stream on which Sydney’s residents relied on for fresh water.

Over two hundred years later, these lessons remain unlearned. While many eagerly await Blainey’s long history, The Story of Australia’s People provides a thought-provoking introduction to how we must learn to live sustainably on the margins of a desert continent. And whether we will still be here in 60,000 years time.

Justin Cahill is a Sydney-based naturalist and historian. His publications include a biography of the ornithologist Alfred North and A New Life in our History, a history of the European settlement of Australia and New Zealand told from the perspective of ordinary people. He has also written on Chinese history, including the negotiations surrounding Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong and its decolonisation in 1997.

Justin Cahill is a Sydney-based naturalist and historian. His publications include a biography of the ornithologist Alfred North and A New Life in our History, a history of the European settlement of Australia and New Zealand told from the perspective of ordinary people. He has also written on Chinese history, including the negotiations surrounding Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong and its decolonisation in 1997.

Justin’s most recent publication is the first part of Epitome for Eleanor: A Short History of the Known Universe, written for children. His current projects include a natural history of Sydney’s Wolli Creek Valley.

He regularly contributes reviews to Booktopia.

REVIEW: Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

REVIEW: Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang  REVIEW: The Three Lives of Alix St. Pierre by Natasha Lester

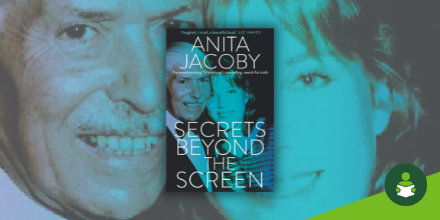

REVIEW: The Three Lives of Alix St. Pierre by Natasha Lester  REVIEW: Secrets Beyond the Screen by Anita Jacoby

REVIEW: Secrets Beyond the Screen by Anita Jacoby

Comments

February 8, 2016 at 11:49 am

I like your review style, Booktopia. Very authentic :). Would love to feature your reviews in our weekly curated email digest that goes out to thousands of people.