This is What I Suspect:

This is What I Suspect:

Stephen Orr on the Appeal of Crime Writing

Ten year old James Ellroy’s mother was murdered in 1958, her body dumped beside a freeway. No one was ever charged, and James lived with this psychological scar as he grew up. No Pride and Prejudice could’ve helped. But he has attempted to fix things by writing about them.

That’s what crime writers do. They’re the ones, I believe, that are tackling the range of complexities that exist around us. They’re the ones willing to talk about why people murder, abduct and abuse kids, why some boys grow up learning to hate women, abuse them, kill them. None of this is ever easy to write about, or sometimes read about, but it’s necessary.

For me, In Cold Blood served as an introduction, but then came Ellroy and books like Masha Gessen’s The Brothers. True crime, always of variable quality, because it’s a relatively new genre, trying to do quite ancient things. And is it any wonder these new authors, reinventing what Dickens tried to do with Fagin and his pre-teen crims, are often journalists or psychologists? Or writers brought up in complexity?

This is what I suspect. That the ‘literary’ novel was an eighteenth-century invention that worked best solving nineteenth and twentieth century problems. By problems I mean all of the stuff our 1.4 kilogram lump of minced meat can’t deal with: why we bother with politics; why, despite our best attempts, violence is ever-present; why some parents screw up their kids.

In fact, it’s a really long list. But we’ve struggled with the novel, and still give its practitioners awards and encouragement. Like these stories are somehow good for us, made of marble, hung on walls. But I suspect their dwindling readership has to do with how well they’re representing, finding solutions to our world today. As Jonathan Franzen said: ‘The actuality is continually outdoing our talents.’

This is also what I suspect. That we’re motivated by love and fear. In Ellroy’s case, My Dark Places was both. Something I feel, too, when I sit down to write these non-fiction stories. Like twelve-year-old Frank Hawson, minding his parents’ outback hut in October 1840 when a group of Aboriginal men came looking for food. He gave them some, but then they asked for his gun, and he refused, and they speared him.

This fear, always present. Of violence, on display most Saturday nights in Adelaide’s Hindley Street. Of losing people close to you. Of fate, of the random nature of existence. Tomorrow morning you’ll be driving to work and you’ll glance at the radio for a moment and someone will step out and you’ll hit them and kill them and you’ll be the criminal, and you’ll pay for it for the rest of your life. Maybe this is why we now hide in our homes, obsess about the perfect meal and renovation.

Maybe it’s modern self-preservation, and maybe this loss of primeval fear, this adrenaline-induced, heart-pumping state that’s kept us alive for hundreds of thousands of years, has been lost, and to replace it we read about it, watch CSI. Maybe we need fear, and maybe this is why this new, complex, surreal, often deranged and difficult genre fills the void. Brings darkness in measured doses, allows us to poke the lion behind the bars with a stick, all the time knowing we’ll be safe.

This is what I suspect. That we want the truth, not nostalgia. We want to understand.

The final word goes to Ellroy, the young boy, waiting for his mother to walk through the door. Learning, quicker than most, that ‘only a reckless verisimilitude can set that line straight.’

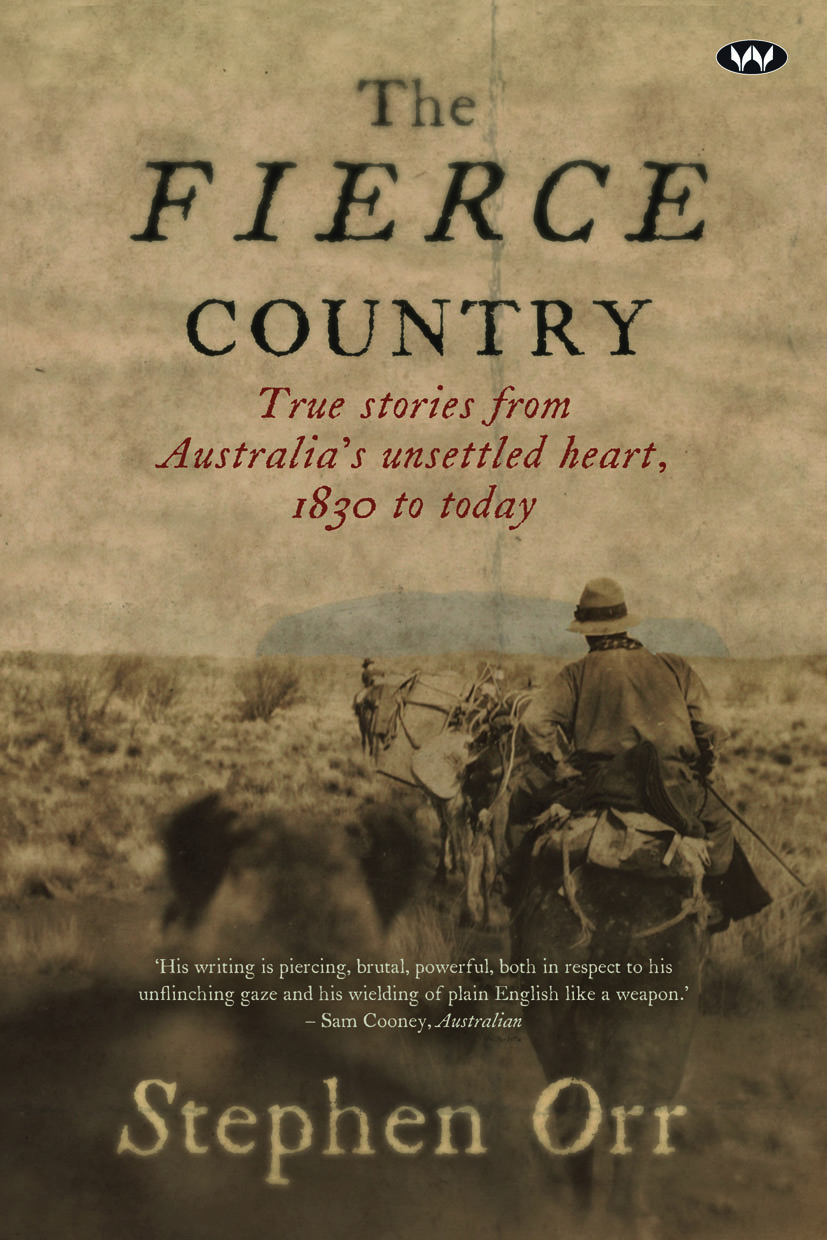

Stephen Orr’s new book The Fierce Country: True stories from Australia’s unsettled heart, 1830 to today (Wakefield Press) is literary true crime that explores Australia’s anxiety about its outer-urban places through true stories of mysteries, murders and disappearances, drawn from 1830 to now.

The Fierce Country

True stories from Australia’s unsettled heart, 1830 to today

The Fierce Country holds no malice, but neither pity. It just sits, and bakes, and waits. We do the rest. We provoke it when we mine above its aquifers. Weaken it, and ourselves, when we leave mountains of asbestos to blow away in the wind. Misunderstand it when we see it as nothing more than a resource. Resent it when it takes our children. The Fierce Country, perhaps, is in our minds as much as anything.

The open spaces and isolated places outside Australia's cities have unsettled us from first European settlement to today - often with very good reason.

In this nail-biting book combining the notorious and little-known, acclaimed author Stephen Orr has collected true stories that have shaped and continue to haunt the Australian psyche: mysteries, disappearances, mistreatment and murder.

Fatal conflicts between an Aboriginal tracker and the police employers hunting his community. An itinerant conman picking up tips for the perfect murder from a famous novelist around a campfire on the Rabbit-Proof Fence. A schoolteacher and her students kidnapped en masse in 1970s rural Victoria. And that fateful day when Peter Falconio pulled over beside a desert highway.

Together these tales chart an undercurrent of shifting cultural tensions as Australians find, lose and question who we are.

REVIEW: Framed by John M. Green

REVIEW: Framed by John M. Green  R.W.R. McDonald answers our Ten Terrifying Questions!

R.W.R. McDonald answers our Ten Terrifying Questions!  REVIEW: Gone by Midnight by Candice Fox

REVIEW: Gone by Midnight by Candice Fox

Comments

No comments