Nathan Makaryk is the author of Notthingham and Lionhearts, and is the general manager and creative director of Improv Shimprov, based in Southern California.

Today, Nathan Makaryk is on the blog to tell us all about how improv shaped his approach to writing good, compelling dialogue. Read on …

Improv comedy and novel writing, on the surface, may seem like polar opposites as artistic mediums. Flying by the seat of your pants with no safety net in front of a live audience tends to be for extroverted performers, whereas an introverted writer’s cave lets them spend hours deliberating over every last word in each sentence. But somehow, I—and a few unfortunate others, I’m sure—have ended up in both worlds.

Some quick background on myself: I’ve been running a highly successful improv group in California for fifteen years, which performs every week (when not in quarantine) and has also performed all over the world through college and cruise gigs. I’ve literally been in thousands of improv shows—and as of September 2020, I’ve also published my second historical fiction novel with a major publishing house. While there’s plenty of comedic banter in my books, they are primarily serious, dramatic works.

However, there’s a surprising amount of overlap in these two worlds. I’d encourage any writer to seek out some local improv classes to help expand their skillset.

SAYING YES

If you’re unfamiliar, the ruling tenet of improv is about saying yes. Occasionally this means literally saying “Yes” out loud, but more often it means saying yes to ideas and embracing them. For instance, one actor might present an idea (something as simple as “Look at this chicken”) and the other actor has to accept, react, and build on that idea (“Wow, that chicken has sunglasses on”) rather than negate the idea (“That’s not a chicken, it’s a fly-swatter, you idiot.”) Not only does this lead to some creative brain-storming, it also builds your own confidence, since anything you say must be supported by your teammate.

You’re less likely to have a teammate when writing, but it’s just as important to say yes to your own ideas. Writers often stare at the blank page, waiting for the “right” inspiration, rather than letting their thoughts flow out.

This is particularly important when writing dialogue: because realistic characters shouldn’t be great at expressing themselves perfectly on the first shot! In real life—especially in emotional moments—we often say the first thing that comes to our mind, which is rarely an indelible Shakespearean monologue. By letting your characters speak off the cuff, they’ll start to bounce ideas off each other, clarify, misspeak and misinterpret each other, and—most importantly—react in real time. This makes dialogue feel more natural and fluid, and separate it from your more carefully crafted non-dialogue sections.

TRY IT

Here’s a simple improv warmup to try with some friends (yes, it can be on a video call):

I call this game Green Gobs, but it goes by many names and is just an exercise in free association. Person A says any word (or phrase) to Person B, and Person B reacts with the first thing that comes to their mind. Person C then reacts to Person B, etc. and you repeat ad nauseam.

Simple enough, but here are the tricks:

1. You can’t prepare something ahead of time. It has to be a genuine instinctive reaction to the word or phrase you receive. Also, it shouldn’t be a reaction to anything earlier in the game. For instance, a bad example might go: “Transformer” > “Electricity” > “Optimus Prime.” It’s pretty unlikely the third person actually thought of “Optimus Prime” from the word “Electricity.” They’re clearly still thinking about “Transformer,” rather than actively listening to what’s coming to them.

2. No hesitating. Don’t stall to think of the “right” reaction. Accept whatever you think of. Immediately.

3. Here’s the hardest part: No apologising. Don’t say you’re sorry for your idea, don’t laugh it off, and don’t shake your head. You have to be proud of your response, and stand by it. No one is allowed to judge you for it, especially yourself.

No, this isn’t a magic wand, and it’s only one small example of what you’ll get out of an improv class—but like any exercise, you’ll notice an improvement over time. You’ll lower your own inhibitions, embrace your instincts, and start “going with the flow”. If you write with that same mentality, your characters’ dialogue will feel more like a living, shifting relationship rather than two people waiting for their turn to talk. Each new line should be a visceral reaction to something that character just heard, which sparks an idea and compels them to speak.

Admittedly, most of what you write this way will be thrown out. Saying yes to your own ideas probably means overwriting, but the advantage as a writer (that you don’t get on stage) is your ability to edit it down later! But it’s better to have all those options than to stare at the blank page and have nothing to edit at all.

—Lionhearts by Nathan Makaryk (Penguin Books Australia) is out now.

Lionhearts

All will be well when King Richard returns . . . but King Richard has been captured. To raise the money for his ransom, every lord in England is raising taxes, the French are eyeing the empty throne, and the man they called “Robin Hood”, the man the Sheriff claims is dead, is everywhere and nowhere at once.

He’s with a band of outlaws in Sherwood Forest, raiding guard outposts. He’s with Nottingham’s largest gang, committing crimes to protest the taxes. A hero to some, a monster to others, and an idea that can't simply be killed. But who's really under the hood?

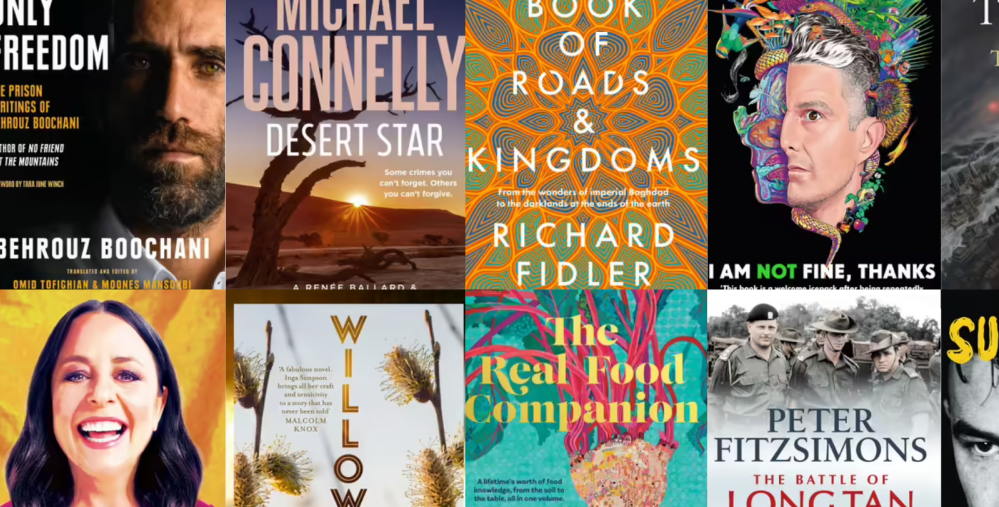

Booktopia’s top picks for Mother’s Day 2023

Booktopia’s top picks for Mother’s Day 2023  Top 10 book deals for Black Friday!

Top 10 book deals for Black Friday!  Top 10 Books for Dad this Christmas!

Top 10 Books for Dad this Christmas!

Comments

No comments