Wendy Orr was born in Canada, and grew up in France, Canada and the USA. After high school, she studied occupational therapy in England, married an Australian farmer and moved to Australia. They had a son and daughter, and now live on five acres of bush near the sea. Her books have won awards in Australia and around the world, and have been translated into twenty-six languages.

Today, Wendy Orr is on the blog to tell us about how Greek mythology has inspired her three latest books, in particular Cuckoo’s Flight. Read on …

I’m not sure why I was so fascinated by the myth of Theseus as a child. Perhaps it was because he was still a teenager when he fought the Minotaur:

Long ago, before Greece was a country or Athens a great city, King Minos ruled the island of Crete. Crete was a rich land and Minos was a powerful king – but he had a problem: his son the Minotaur was born with the head of a bull. His father hid him in a maze in the middle of the palace – and the Minotaur ate everyone who came into it. So when another of Minos’s sons was murdered by a man from Athens, Minos demanded revenge that also solved the problem of feeding this monster. From now on, every year (or every nine years, depending on who’s telling the story) the small city-state of Athens would have to send seven youths and seven maidens for the Minotaur to eat.

However, Theseus, who’d just discovered that his father was the king of Athens, bravely volunteered to be one of the tribute group. With the help of King Minos’s daughter Ariadne he killed the Minotaur, led his friends safely out of the maze – and no one was ever sent there to be eaten again.

Even leaving out the many complications of this story – Theseus is also the son of Poseidon, the god of the sea – it’s obvious that it’s entirely fiction. Bull-headed monsters don’t exist, and if they did, wouldn’t they eat grass as bulls do, rather than people?

Then, in 1899, the British archaeologist Arthur Evans excavated the palace of Knossos in Crete. One of the many extraordinary finds was a fresco of two girls and a boy doing back flips over a bull. What if the folk memory of this was the basis for the story of youths being sacrificed to a man-eating bull?

That’s obviously what Mary Renault wondered when she wrote The King Must Die in 1958, and what I wondered when I wrote Dragonfly Song in 2016. I’d read Mary Renault as a twelve year-old and the stories stayed with me, although when I reread I was slightly repelled by Theseus’s toxic masculinity, realistic as it probably was.

It was a long road between falling in love with legends and their reinterpretations and writing my own Bronze Age trilogy, as Swallow’s Dance and now Cuckoo’s Flight followed Dragonfly Song. Research wove back and forth between mythology and archaeology and culminated with a trip to visit the sites of my stories in Crete and Santorini. Studying an era so far in the past means that even archaeologists argue bitterly over key dates and theories that are just as fascinating as the myths. In writing fiction I have to choose what makes sense for me and my story – even the most interesting facts have to be condensed, simplified or omitted to let the story flow.

It was a long road between falling in love with legends and their reinterpretations and writing my own Bronze Age trilogy, as Swallow’s Dance and now Cuckoo’s Flight followed Dragonfly Song. Research wove back and forth between mythology and archaeology and culminated with a trip to visit the sites of my stories in Crete and Santorini. Studying an era so far in the past means that even archaeologists argue bitterly over key dates and theories that are just as fascinating as the myths. In writing fiction I have to choose what makes sense for me and my story – even the most interesting facts have to be condensed, simplified or omitted to let the story flow.

What fascinates me most, not just as a writer but as a human, is the people who lived in these times. How did it feel to grab the horns of a racing bull and somersault down its back, watched by a crowd of elegant palace folk? Were you a slave or a rock star – or both? No matter what our beliefs, fear hasn’t changed over the millennia, and I doubt that desire for fame and recognition has either. But then, as now, individuals vary in how they deal with those emotions.

‘Times change, beliefs and morals alter, but human emotions don’t. That’s why myths were born, and why stories continue.’

Minoan Crete led me quickly to Santorini, where in 1967 a sophisticated city was discovered under ninety metres of ash. Akrotiri had lain buried since one of the biggest volcanic eruptions in history, four thousand years ago. Some theories say that no one died in it, because no unburied bodies have been found so far – so I started wondering, where and how did those people escape? How would their lives have changed as they fled a life of elegantly decorated homes, complete with flushing toilets, and found themselves refugees? Were they welcomed by their sister civilisation of Crete, or did a mass evacuation of the island make them an unwanted burden? I played with these questions for months as I planned Swallow’s Dance – until I visited the archaeological site and heard the latest theories. It now seems that no on the island could have survived. Maybe I get overinvolved with my characters, but I was devastated. Even if my protagonist escaped, how could you deal with the loss of everyone you knew, and your land itself?

By contrast, exploring the site of Gournia in Crete was a joy. The ruins of this Minoan village have a calm energy that belie the bustling town it must have been. I was lucky enough to explore it with a wonderful archaeologist who’d worked on the excavations, the late Dr Sabine Beckmann. We’d become friends over several years of emailing – she was the kind of person who, when I asked questions about the production of purple dye, dived to get a murex shell, extracted the gland and dyed a silk shirt with the result. Her explanations as we walked around the remaining walls of the town brought it to life – and when we stood on a pottery workshop floor, where she pointed out that the ground was still soft powdered clay instead of the rocky ground of the rest of the site, I knew that my protagonist had to become a potter. Sabine also drilled me on the differences between the different eras of the potsherds we picked up on the site – is this 1800 BCE or 1600? Why? A few days later, trekking down a steep path from a Minoan sanctuary, now covered by a radio tower, I picked up a shard of a glazed pot. I was sure I could make out the Cretan hieroglyph of an olive tree. ‘No,’ said Sabine, ‘that’s just a scratch from being pushed down the hill for 4000 years. But there’s a thumbprint on the side.’ I put my thumb on it, and it fitted.

By contrast, exploring the site of Gournia in Crete was a joy. The ruins of this Minoan village have a calm energy that belie the bustling town it must have been. I was lucky enough to explore it with a wonderful archaeologist who’d worked on the excavations, the late Dr Sabine Beckmann. We’d become friends over several years of emailing – she was the kind of person who, when I asked questions about the production of purple dye, dived to get a murex shell, extracted the gland and dyed a silk shirt with the result. Her explanations as we walked around the remaining walls of the town brought it to life – and when we stood on a pottery workshop floor, where she pointed out that the ground was still soft powdered clay instead of the rocky ground of the rest of the site, I knew that my protagonist had to become a potter. Sabine also drilled me on the differences between the different eras of the potsherds we picked up on the site – is this 1800 BCE or 1600? Why? A few days later, trekking down a steep path from a Minoan sanctuary, now covered by a radio tower, I picked up a shard of a glazed pot. I was sure I could make out the Cretan hieroglyph of an olive tree. ‘No,’ said Sabine, ‘that’s just a scratch from being pushed down the hill for 4000 years. But there’s a thumbprint on the side.’ I put my thumb on it, and it fitted.

The goosebumps of that thumbprint are partly why I stayed with this family for Cuckoo’s Flight. The other reason is that it seems Gournia wasn’t completely destroyed or depopulated when the Mycenaeans – the Homeric heroes – gradually invaded and took over Crete. I wondered what the town’s experience had been. Could there have been some victories that ensured its survival for the next couple of centuries? And – because stories always start from an intermingling of a variety of thoughts, and my sister was riding horses in Mongolia at the time – I also started wondering about horses. Crete has indigenous ponies, and although chariot use, as well as a statuette of a priestess riding side-saddle, seem to date from after the Myceanean take-over … if horses were there, surely someone had thought about riding them before that.

So I gave my protagonist Clio a Trojan father, because by Homeric times at least, Troy was known for its horse raising – and I didn’t find it difficult to channel my inner horse-crazy girl who still grieves at not being strong enough to ride. Which is why my Clio was also disabled, because all our characters spring from some subconscious part of us, and that part of me didn’t let this character come to life until I accepted that she couldn’t ride either. Which started me off on a whole new line of research into chariots, bridles and Hittite horse-training manuals …

Unlike the Theseus story behind Dragonfly Song, or Atlantis behind Swallow’s Dance, there was no one myth behind Cuckoo’s Flight. Instead, there was the spirit of many: of the centaurs, of Pegasus, of Achilles’ immortal horses, Hector the horse tamer of Troy, the horses and chariots of many different gods … All these stories tell us of the human longing for the freedom, power and pure joy of being with a magnificent horse. Times change, beliefs and morals alter, but human emotions don’t. That’s why myths were born, and why stories continue.

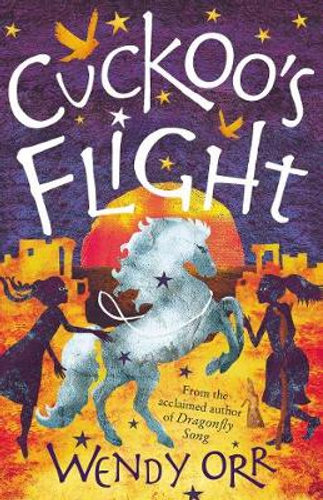

—Cuckoo’s Flight by Wendy Orr (Allen & Unwin) is out now.

Cuckoo's Flight

When Clio's town in Bronze Age Crete is threatened by seafaring raiders, she faces the greatest sacrifice of all. Can Clio, her herd of horses and a new young friend find a way to change their destinies?

When a raiders' ship appears off the coast, the goddess demands an unthinkable price to save the town - and Clio's grandmother creates a sacred statue to save Clio's life. But Clio is torn between the demands of guarding the statue and caring for her beloved horses...

Bestsellers: Scott Pape and Ash Barty continue to prove a hit with readers!

Bestsellers: Scott Pape and Ash Barty continue to prove a hit with readers!  Bestsellers: Jane Harper and Aunty Donna prove a hit with readers!

Bestsellers: Jane Harper and Aunty Donna prove a hit with readers!

Comments

March 31, 2021 at 8:21 pm

Fascinating, Wendy. I love hearing about your inspirations, research and the questions you pondered while writing your wonderful stories.