Jon Klassen is the creator of the New York Times bestselling I Want My Hat Back and its companions This Is Not My Hat, which won a Caldecott Medal and a Kate Greenaway Medal, and We Found a Hat. He is also the illustrator of Extra Yarn, Sam and Dave Dig a Hole, Triangle, Square and Circle, all by Mac Barnett, and House Held Up by Trees by Ted Kooser. Originally from Niagara Falls, Ontario, Jon Klassen now lives in Los Angeles. Find him on Instagram as @jonklassen and Twitter as @burstofbeaden.

Today, to celebrate the release of his new picture book The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen is on the blog to take on our Ten Terrifying Questions – read on!

- To begin with why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself – where were you born? Raised? Schooled?

I was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, and the mostly raised in Southern Ontario, Canada. I went to college outside of Toronto for Animation and then got work in California working at the studios and even though I don’t work at the studios anymore, I still live in Los Angeles and make the books here.

- What did you want to be when you were twelve, eighteen and thirty? And why?

Probably twelve and eighteen looked pretty similar, aspiration-wise. I was very into the idea of working in animation. I loved that it was a legit job in the world that you’d go to every day and feel like a person with a job but it also involved making things and drawing. By the time I was 30, though, I’d done a fair amount of time at the studios and I’d found book work to be a lot more up my alley, and my hope then, as it is now, is just to keep getting to make things like this. It’s a very good job to have.

- What strongly held belief did you have at eighteen that you don’t have now?

I think at eighteen I thought that if you couldn’t write it down, you didn’t really have an idea yet, that you hadn’t done enough work yet, and now I feel like the best stuff is the stuff you write around, that language hasn’t really gotten to (at least not my grasp on language). I really had to make some things of my own and watch them go out into the world and see people pick up on subtle things that I didn’t even consciously include to believe in this, and also admit to myself that that was what really got me about other peoples’ work that I admired.

- What are three works of art – this could be a book, painting, piece of music, film, etc – that influenced your development as a writer?

The Road by Cormac McCarthy – this was the first book of his I read, and I read it just as I was starting to make books and work of my own. I’d been worried that my sensibilities were so graphic and simple that it was going to doom me to doing only kind of flat, stylised stories that shied away from any kind of story or character substance, for a lack of information, but when I read The Road it was this huge example of how you can get at the deepest stuff not even in spite of, but because of your economy. Everything he leaves out, both expositionally and stylistically, works to bring you in, not keep you out. It was huge.

Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel – these early reader stories still hold huge influence over me, and I think for the same reasons they grabbed me so hard when I was very young. Everything about the format and the illustrations is welcoming and warm and meant to make you feel cosy, and yet Frog and Toad’s relationship has all sorts of uncosy complexities and uneven parts that fuel their talks and problems. Lobel seems uninterested in solving these problems, and the assumption there is he thinks relationships sort of are what they are and we are who we are inside of them. Children are aware of complex relationships, and seeing a book lay that out, so gently and funnily, and still manage to make a whole breathing world around it somehow is hugely inspiring.

Blue Velvet by David Lynch – this was the first David Lynch film I ever saw, and I saw it fairly late, in my mid-twenties. We weren’t exposed to a lot of darker stuff growing up, so I’ve always been a little sensitive to it, and don’t mind turning things off if they are making me feel Bad. And when I finished Blue Velvet I realised that the film had been full of things that would ordinarily have made me feel Bad, but the attitude of the film had somehow made me feel hopeful instead. There was a curiosity and a trust that it fostered. It wasn’t trying to expose you things in a condescending way. Even though it was willing them into existence itself, it was showing you people and events in a way that managed to preserve how it feels to see certain things happen for the first time, and realise what the world is capable of. It didn’t try to explain why, it literally asks the same questions you would ask, and that’s all. It changed how I thought about what I thought ought to be made, and showed me that it was ok to make things that felt dark and sad and unexplained because you could do it in a way that signaled that other people felt that way about those things too, and there was a huge hope in that.

‘I like strict rules to play with and react to, and children’s books have many many rules that come with them. There’s a forced brevity to everything that suits me, I think.’

- Considering the many artistic forms out there, what appeals to you about writing a children’s book?

I really need some kind of narrative to get started on anything, I think. Not only that but I like strict rules to play with and react to, and children’s books have many many rules that come with them. There’s a forced brevity to everything that suits me, I think. Without it I turn into an open faucet with no design or point to anything I’m saying. Visually the whole point is clarity, and that suits me, too. You can start with a very simple visual premise and then open up all kinds of murky things behind it that make the book interesting for me as an adult to make, but very young kids still get (hopefully) satisfied by the visual resolution, and keeping my eye on that resolution for them keeps me in check generally. It’s a very useful format. It’s worth saying too that I think of the books as being FOR children. I don’t want it to sound like I’m using the format as a trojan horse for Real Ideas, I really like making things for kids. They are a very open-minded and intelligent audience, usually, and I feel lucky to get things in front of them.

- Please tell us about your latest book!

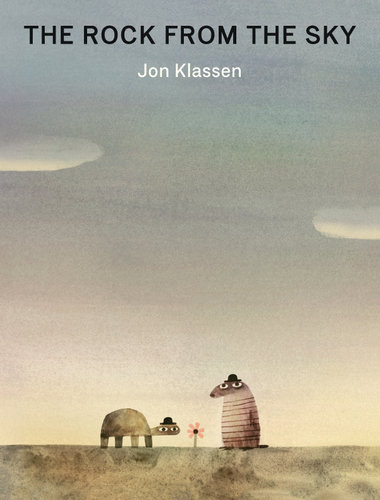

The Rock From The Sky is a picture book that contains five short connected stories. It involves very little action – it’s mostly a small cast of characters (a turtle, an armadillo/mole/thing, a snake, and, later, a giant alien) moving horizontally across a low landscape, but it also involves time travel, aliens, betrayal, near death experiences, and actual death experiences.

- What do you hope people take away with them after reading your work?

I hope they have fun, I guess, first and foremost. I don’t have a clear message to deliver, but I hope there’s that same feeling of inclusiveness and hope in the general storytelling that I talked about earlier in the work I admire.

- Who do you most admire in the writing world and why?

I mentioned Cormac McCarthy earlier and he’d be pretty high on the list. He’s managed to set up a life where he doesn’t concern himself much with the literary scene, his daily life seems surrounded by inspiration from elsewhere, and he takes all the time he needs to get something done, to say nothing of the work itself. It’s a really good setup, from here, anyway.

- Many artists set themselves very ambitious goals. What are yours?

I don’t know how ambitious it is, but I’d like to carve out and maintain stability in my life and keep working in whatever direction the work leads and not go back over old territory too often. I guess that actually could seem hugely ambitious.

- Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

For writers of children’s things in particular, I haven’t found too many problems with the philosophy of doing a lot less than you think you need to. It’s not that you need to be lazy about it, it’s just that there’s so much more in a small idea than we think at first, and books or stories shouldn’t try to hold the whole world in their hands, they only ever hold small parts of it, and it’s good to admit that and try to make those small parts as good as they can be.

Thanks!

—The Rock from the Sky by Jon Klassen (Walker Books Australia) is out now.

The Rock from the Sky

Turtle really likes standing in his favourite spot. He likes it so much that he asks his friend Armadillo to come over and stand in it, too. But now that Armadillo is standing in that spot, he has a bad feeling about it...

A hilarious meditation on the workings of friendship, fate, shared futuristic visions, and that funny feeling you get that there’s something off somewhere, but you just can’t put your finger on it...

Ten Terrifying Questions with Deborah Abela

Ten Terrifying Questions with Deborah Abela  Ten Terrifying Questions with Terri Libenson!

Ten Terrifying Questions with Terri Libenson!  Ten Terrifying Questions with Charlie Archbold!

Ten Terrifying Questions with Charlie Archbold!

Comments

No comments