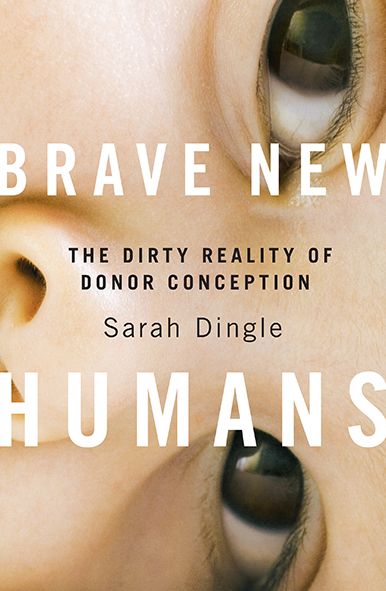

Journalist Sarah Dingle was 27 when she learnt that her identity was a lie. Over dinner one night, her mother casually mentioned Sarah had been conceived using a sperm donor. As the shock receded, Sarah put her professional skills to work and began to investigate her own existence. In a profoundly personal way, Sarah Dingle’s book Brave New Humans shines a light on the global fertility business today – a booming and largely unregulated industry that takes a startlingly lax approach to huge ethical concerns, not least our fundamental human need to know who we are, and where we come from.

Below, we have an extract from Chapter 2 of Brave New Humans to share with you. Read on …

Brave New Humans: Chapter 2

What happened in that hospital room would mark me indelibly for years. Everything there was alive and remarkable in some way – the sounds too loud, the colours off – except, in the end, my father. But there was something else there too, another layer I couldn’t see.

Despite the evidence of all my senses, what happened there that day was not the full story. That would take another twelve years to emerge, in that restaurant on a Saturday night.

After the Easter dinner revelation, I went home that night in a daze. I don’t know how I got there. In my flat, I curled up on the couch and bawled. There’s no other word for it.

Somewhere in the middle of it, I rang my then-boyfriend, who was overseas, and choked out what had happened.

‘She said he’s not my father,’ I mumbled.

‘She WHAT?’ ‘He’s not my, my father.’

‘What does she mean? Did she have an affair?’

‘They used [hiccup], used a donor.’

‘WHAT?’

On the line, my boyfriend was silent.

‘I don’t know what to say,’ he said eventually.

I wailed some more. He comforted me. Then I said what was really on my mind:

‘He’s not my father,’ I hiccupped. ‘Dad, he’s not … he’s not mine.’

I’m no shrink, but I now know that when you find out you’re donor-conceived, there are a number of different common emotional stages. As with all processes, it depends on the individual. You may skip some, or linger in others.

My first stage was grief. The man I thought was my father had died when I was fifteen. Now, twelve years later, I was back at the funeral, in baking hot Adelaide, with cicadas screaming. The scene was the same, but I was different. I was an interloper, because: he was never mine in the first place.

I’d always believed that when someone dies, if you love them, they are yours forever. Until now, it had been a comforting thought.

I had been tricked. I felt like a fool. I had lost even that.

Over the next few months, I carried on as normal. I went to work. I was then a reporter with the ABC’s 7.30, a national daily TV current affairs show. It was a job I’d wanted for years. It was also a demanding job at the best of times. This was not the best of times. I tried to keep my shit together. I told a select few people. Mostly, I didn’t tell people.

I was a mess.

In the mornings I looked at myself in the mirror and I didn’t know what I saw. I didn’t recognise myself. When you grow up Asian in Australia, it’s easy to forget how different you look to those around you. Most of my friends are white. My partner is white. Advertisements, magazines, newspapers, everything on Australian television from the news to the trashiest reality TV show is overwhelmingly white. Even my workplace, the public broadcaster, is still an extremely white institution. In photos or TV footage from work, surrounded by mostly white people, I’m sometimes surprised by how much I stand out. But there had always been a magnetic connection to my own face: I am different but I am who I am.

Now that connection was broken.

The mirror was different: it was worse. I now didn’t understand what I saw, as if my brain couldn’t decode it. My face had become just colours and mass. Its shape was completely meaningless. It was not a face: it was a thing. I knew nothing about myself.

Standing in front of the mirror and struggling, I thought: maybe being only half Chinese can help me work my way back to some sort of solid ground. Because it’s obvious that my biological father was not Chinese. Maybe he was Anglo-Saxon, like I’d always believed. Maybe he wasn’t.

I studied my face again. I tried to separate the Chinese (the known) from the other (the unknown). It was impossible.

A whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Unfortunately, the flipside of that is: a whole cannot be broken down into those parts and still retain its meaning. With only one known biological parent, trying to work out what came from whom is like trying to reduce a cake to its original ingredients after the whole mess has already been baked.

Some mornings, I thought about it in mathematical terms: if I have the answer, can I work out what the equation is? And of course I couldn’t. The equation could be anything. I could be almost all my mother’s child, or virtually none. I have dark hair. I have dark brown eyes. I have light skin which can tan quite dark. I am of medium height. I have a straight nose. All of those traits could have come from either my mother or my father.

How do you take something away from a face and expect to understand what’s left?

All of these thoughts would scream their way through my head every morning in front of the mirror, and then I’d go to work, where I was supposed to make stories about the big issues facing our nation. It wasn’t ideal. On top of all that, I was managing a chronic pain condition.

Six months before I’d learned about my conception, I’d been vacuuming at home in the flat with the music cranked up loud. Suddenly, there was a bolt of extreme pain across my hips like an iron bar. Black came down over my eyes. When it passed, I staggered to the bench where my phone was. I called my mother and told her something was wrong, that she had to come and find me. Then I passed out.

‘With only one known biological parent, trying to work out what came from whom is like trying to reduce a cake to its original ingredients after the whole mess has already been baked.’

I woke up on the floor. The music was still going. I tried to get up, but I couldn’t raise a single limb without a giant wave of pain and fear going off in my brain. It made me pass out again, and when I came to, I just lay there. I knew I wasn’t paralysed because I could move my fingers and my toes. After what I think was a couple of hours, my mother and some paramedics broke in. They got me up, and into bed.

Over the next weeks, months, years, from MRIs, CTs, physio, osteo, chiro, acupuncture, massage, neurosurgery and pain clinics I learned that I had a herniated disc. It’s a very common injury, although less common among people in their twenties. The disc which had ‘slipped’ (such an awful term) was also desiccated – it had lost its sponginess. The muscles around it had gone into spasm, and this was something that I’d have to manage ongoing.

Unfortunately, chronic pain is not purely physical: to a certain extent, it’s inextricably linked to your state of mind. Finding out that my father was not my father, and failing to recognise my own face in the mirror, meant that I was in a lot of physical pain. And I was extremely depressed. The pain was coalescing with all the grief I still felt for my dad. When Dad died, I thought maybe that was the worst thing that would ever happen to me in my life.

It seemed ridiculously unfair that someone could die twice.

I had to leave 7.30. Every few months, it seemed, some other bad thing would tip me over the edge and I would be back on the floor again, paralysed, immobile for a week or more. When I was mobile and able to work, I couldn’t do more than four hours a day without crippling pain. I moved to radio current affairs, trudged home early each day to the same flat where I’d collapsed, to spend my afternoons in agony feeling useless. I wasn’t even thirty and my life was over. Which just made the depression worse. And then the pain, and so on, in a terrible spiral.

But a few things saved me. For a start: I did new things. Working only half days, I was bored out of my mind, so I enrolled in a creative writing course at night, making things up (which, after years of journalism, felt like a holiday). I was still in massive pain. I dealt with this by lying on top of a row of desks at the back of the lecture room, while the rest of the group sat at the front. It was weird, but they bore it admirably: writers are very forgiving of idiosyncrasies.

I had heaps of leave, so I terrified myself by abandoning my support structures and went on a six-week trip to Italy to get away. If I couldn’t have my dream job ever again, I was definitely going to eat good food, and if my life was over I decided I’d rather spend the rest of my cash in Euros than on miserable things like MRIs. To get around the pain, I planned wacky short flights to get there with many stopovers. I did stretches on the ground at airports, train stations and car parks. I spent a lot of time in various Italian AirBnBs, flat on my back in the room, either resting or meditating. I think my hosts thought I was mad. Back in Sydney, I ended my relationship of around six or seven years. I moved out on my own, into share housing with strangers, which scared me because: what if I collapsed again? But being afraid and exhilarated was better than being stuck in the wheel of sameness and sadness.

And, behind it all, I was still thinking about what my mother had told me. My thirtieth birthday was approaching. I’d changed a lot of stuff, ended a lot of stuff, but what did I need to put in place?

In a classic Type A personality moment, I drew up a list. (It was titled ‘F*ck My Life: Things To Do.’) All items on the list were in caps, with boxes to be ticked. There were short-term goals (‘ROLL OVER SUPER’) and very, very long-term ones (‘BUY HOUSE’). At the bottom of the list was: ‘FIND BIOLOGICAL FATHER’. I stuck the list on the wall.

Journalism is the first draft of history, as the cliché goes, but maybe a better way of putting it would be: journalism is a running update on society. Anything that happens to a journalist is grist for the mill. I didn’t know who I was, I didn’t know anything about my life, or my future, anymore, or even what sort of a future I could manage. So, I decided, I would journalism my way out of this hole.

I would investigate.

This is a book about the maelstrom of donor conception – stranger than you thought, and more widespread than you probably realise. It is not a book about the desires of would-be parents. It is not a book about couples engaging in fertility treatment using their own biological material. This is a book about the human beings born of third-party material. This is a book about creating life from collected human tissue, not social relationships.

This is a book about breeding humans.

—Brave New Humans by Sarah Dingle (Hardie Grant) is out now. Limited signed copies are available only while stocks last!

Listen to our podcast with Sarah Dingle below.

Brave New Humans Brave New Humans Brave New Humans Brave New Humans Brave New Humans Brave New Humans Brave New Humans

Brave New Humans

Limited Signed Copies Available!

Journalist Sarah Dingle was 27 when she learnt that her identity was a lie. Over dinner one night, her mother casually mentioned Sarah had been conceived using a sperm donor. The man who’d raised Sarah wasn’t her father; in fact, she had no idea who her father was. Or who she really was.

As the shock receded, Sarah put her professional skills to work and began to investigate her own existence. Thus began a ten-year journey to understand who she was...

What do we know about the Boy Swallows Universe Netflix show?

What do we know about the Boy Swallows Universe Netflix show?  Booktopia’s top thrilling fiction picks for Crime Month

Booktopia’s top thrilling fiction picks for Crime Month  Booktopia’s Top First Nations Book Recommendations for 2023

Booktopia’s Top First Nations Book Recommendations for 2023

Comments