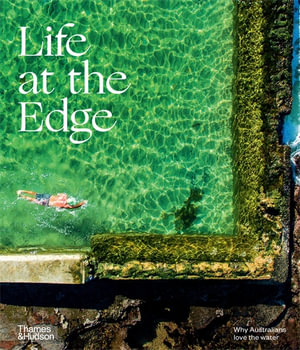

Water features prominently in the collective memory and national identity of Australia. From long summers spent building sandcastles and learning to swim, to the sheer immensity and wild beauty of cliffs and dark oceans, our status as an island nation is inescapable. Collaborating with photographers from around the country, Life at the Edge is a collection of expansive panoramas and detailed closeups showcasing all the textures and tenors of water in Australia: rugged coastlines to ocean pools, mirror-like lakes to micro details of seaweed and shells.

Today, we’re featuring an extract from the book written by Dr Deborah Cracknell, in which she explores the vital question: just why do Australians love the water so much? Read on …

So, why do we love water?

by Dr Deborah Cracknell

Whether we realise it or not, we are all influenced by our surroundings, and different environments can have a profound effect on how we feel. For many of us, spending time in unthreatening natural environments has a much more positive effect on our physiological and psychological health than built settings: we often intuitively respond to the stress in our lives by seeking out natural environments, especially those that contain water, such as rivers, lakes and the coast. This is because we perceive aquatic environments to be particularly restorative: they create strong positive reactions that improve our mood and promote recovery from stress and mental fatigue.

Of the many theories and approaches proposed to explain why we are drawn to and gain physiological and psychological benefits from natural environments, two of the most dominant are the Stress Recovery Theory and the Attention Restoration Theory.

The Stress Recovery Theory proposes that, during our evolution, humans developed immediate and involuntary emotional and physiological responses to aspects of natural environments. When faced with an acutely stressful situation, the body’s sympathetic nervous system triggers a fight-or-flight response, which mobilises the body for action: our breathing rate in-creases, the heart beats faster, digestion decreases, and glucose is released from the liver for energy. Activating these bodily systems requires energy and is therefore physically exhausting. Although the fight-or-flight response evolved to enable humans to swiftly respond to danger, elements of city living (e.g. over-crowding, loud noises) and everyday life (e.g. the daily commute, work pressure) can also induce this acute stress response. Repeated activation of this response can negatively impact physical and mental health, and such chronic stress may result in high blood pressure, poor sleep, depression and anxiety. However, just as the human body instinctively reacts to negative stimuli, it equally responds to positive stimuli in the natural environment, such as water. In this instance, the parasympathetic nervous system stimulates the body to ‘rest and digest’: breathing slows, heart rate decreases, digestion increases, and the body’s energy supplies are maintained – the body is restored to a state of calm. Therefore, natural settings, such as forests, mountains, lakes and the coast, can promote these more positive emotions and revitalise energy levels by providing a valuable ‘breather’ from our stresses.

The Attention Restoration Theory focuses on the restoration of ‘directed attention’, which is when a certain task requires effort and does not automatically attract one’s attention. Prolonged or intense periods of concentration can be mentally exhausting and, as we struggle to focus, we become easily distracted, irritable and impatient; before long, we need to take a break. This theory proposes that our mental fatigue could be reduced by spending time in, or even simply viewing, a restorative environment. As we find nature intrinsically fascinating, viewing natural environments takes no effort and this undemanding attention allows our brains to rest and mentally recover.

Natural environments containing water are especially captivating, engaging all of our senses. Watching a raging river, hearing a thundering waterfall, running our hands through a cool stream, licking salt from our skin and smelling the ocean are all sensory experiences that can transform our moods and stir our emotions.

As vision is our most dominant sense, colour is an important part of our sensory experience and, while water is naturally clear, we associate water most positively with shades of blue: the turquoise of tropical seas to the sapphire blue of the ocean depths. Potentially, we are intuitively drawn to the colour blue as we associate it with fresh water and food. However, we also associate blue with feelings of calm, tranquillity and healing, so we may be drawn to water as we instinctively find it soothing and restorative.

The interplay between water and light can also capture one’s attention, creating patterns that we find fascinating. One type of pattern is a fractal – a term first used in 1975 by mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot – which occurs when a pattern repeats itself as it gets larger or smaller. Although some fractals are ‘exact’, meaning the pattern repeats itself exactly, the fractals found in nature are more random: a tree trunk dividing into smaller branches, a river delta, snowflakes, ocean waves, lightning. Studies have found that viewing the type of fractal pattern experienced in nature can induce ‘alpha responses’ in the brain, indicative of a relaxed, yet awake, state. This is why watching waves break on the shore, for instance, can be relaxing, calming and, for some, can ‘wash away’ upsetting emotions.

Comparatively, less research has focused on nature experiences with our other senses, despite their undoubted evolutionary importance for our survival. Sound, however, appears to have received more attention than touch, taste and smell, with several studies highlighting our preference for sounds of nature, such as water, wind and birdsong, over anthropogenic sounds, such as traffic noise. Water arguably has as many sounds as it has colours: a gurgling brook, a tropical rainstorm, the sea washing across and through pebbles, or waves crashing on the shore. These sounds can create a range of feelings and emotions: they can exhilarate and excite, rejuvenate and energise, or relax and calm. The sound of water can be therapeutic and stress-relieving.

While our various sensory experiences in nature are not equally represented in research, there does appear to be an increasing awareness of and drive to explore our other senses like smell, taste and touch. This further work may be especially important considering that we can, quite literally, immerse ourselves in water: swimming and bathing, for instance, create an altogether different way to experience the natural world that is not possible on land.

Water can mean different things to different people: it is a medium in which to relax, reflect, socialise and achieve. Water captivates, calms, invigorates and excites us. This is why we love it.

—Life at the Edge edited by Jo Turner, published by Thames & Hudson Australia, AU$59.99. Available 26 October.

Life at the Edge

Why Australians Love the Water

Capturing that often inexplicable feeling of being in, near and around water, this book is a photographic celebration of Australian coastlines, rivers and waterways.

Water features prominently in the collective memory and national identity of Australia. From long summers spent building sandcastles and learning to swim, to the...

Read an extract from Country: Future Fire, Future Farming

Read an extract from Country: Future Fire, Future Farming  Read a Q&A with the co-editors of The Nordic Edge

Read a Q&A with the co-editors of The Nordic Edge  RECIPE: Neenish Tarts from Australia: The Cookbook

RECIPE: Neenish Tarts from Australia: The Cookbook

Comments

No comments