Chelsea Watego is a Munanjahli and South Sea Islander woman born and raised on Yuggera country. First trained as an Aboriginal health worker, she is an Indigenous health humanities scholar, prolific writer and public intellectual. When not referred to as ‘Vern and Elaine’s baby’, she is also Kihi, Maya, Eliakim, Vernon and George’s mum.

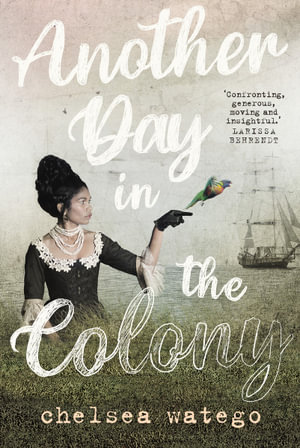

Today, we’re featuring an extract from Chelsea’s first book, Another Day in the Colony — an essay collection that freshly examines the ongoing racism faced by First Nations peoples in so-called Australia. Read on …

nothing but blue skies

I must admit, there was a time when I much preferred the idea of not thinking or talking about racism. It is after all, as Toni Morrison notes, a ‘distraction’ from doing the things we are meant to be doing in this world.

I remember my first job after graduating from university was as an Aboriginal health worker in a town called Dalby in south-west country Queensland. It was on the eve of the millennium and I was just nineteen years of age. I was constantly being distracted by racism. On my first day I was advised of how grateful I should be in having been appointed to the role of ‘Operational Officer Level 3’ as it was previously classified as level two, which was trainee level. The increase was in recognition of my university degree, yet I’m certain that the person who cleaned my office got paid more than me. I don’t know what degree qualification the cleaner had to justify their position on the pay scale but I do know that health professionals who have degrees are typically situated in the Health Professional (HP) stream of the workforce. Yet here we were at the turn of the century and the only racially based health professional workforce in the Australian health system was situated among the cleaners; not even the administrative staff.

At that time, in that town itself, racism was of a real, overt kind. The ‘don’t go to the RSL; they don’t like Blackfullas’ kind, the using racial slurs freely in work-sponsored cultural awareness training kind, the police randomly yet routinely pulling you over and ripping your registration sticker off your windscreen kind, the refusing to rent you a house kind.

I learnt a lot about race and racism in Dalby, through its overtness in the town, and the performed politeness from the white nurses in my workplace. I remember how I stopped booking the work car for home visits and community meetings because it was just too tiring navigating the surveillance and patronising concerns about how and why I was booking a vehicle, which came from people who were not even my supervisors. Some weeks the cars would be all booked out for the week by Monday morning, and I couldn’t help but feel it was to prohibit my access, as though they had a more rightful use to the work vehicle even though I was to cover a whole district on my own.

I’ll never forget the time when the husband (my boyfriend at the time) had to kick the winning goal in a rugby league game against Goondiwindi. I remember this because it was one of those memorable race moments we have in our lives. It was a Sunday afternoon home game and, in a town that had but a few traffic lights, Sunday home games were an event. The club wasn’t segregated, but in the stands there was a mob of Blackfullas who sat together. Certainly in the pig pen there was a little more mingling.

‘Here we were at the turn of the century and the only racially based health professional workforce in the Australian health system was situated among the cleaners.’

It had been a close game and it was getting near to full time when Dalby went over for a try to equalise. The goal kick would put Dalby ahead by two; however, the try scorer had scored in the far corner. It was left to my husband to convert from the sideline, the same side as the stands and the pig pen.

Everyone was quiet, hanging on edge. I’ve watched him kick from the sideline countless times and I knew he could do it, but I was nervous. If there was ever a time to kick that goal it was that day. As he was lining up the kick for what seemed like an eternity, a lone voice came from the pig pen, ‘White men can’t jump; Black men can’t kick!’

There was dead silence. I could feel the tension and I wanted so much more for him to make the kick. He walked back to reposition the ball on the tee. My heart was thumping. Everybody was waiting anxiously. He got up and slowly took those long straight strides backwards from the base of the football. And then he retraced those same steps, slow and then faster to kiss the ball with his foot.

From the sound of the boot hitting that ball, I knew he’d struck it good. The ball seemed to linger too long in the air. It was heading in the right direction, but we all knew at any time it could veer off or fall short. We all sat silent as that ball swirled in the air. It wasn’t until the touch judge raised the flags to confirm the conversion that we screamed, like proppa screamed, jumping up and down in the rickety wooden grandstands.

It wouldn’t have mattered had Dalby not won, because Blackfullas won that day. I love when Blackfullas win, for the simple fact that we are never meant to win. The odds are always stacked against us to make sure we don’t because the game is rigged by race. But I remember that win like it was yesterday and I have continued to chase it ever since.

It reminds me of the first try scored in the very first Indigenous All Stars rugby league game in 2010 when Wendell Sailor scored on the sideline. I was at that game on the very side he did it. It wasn’t the try so much but the post-try celebration, where he pulled the corner post out and proceeded to mimic playing it like a didgeridoo while his Indigenous teammates did shake-a-leg around him. All the Blackfullas in the stand screamed and cried that day.

I still get goosebumps when I watch it again. It was the cheekiness in winning against the whitefullas but, too, what that act represented. The corner post represents the parameters within which the game can be played, and removing it, in that particular context of an Indigenous versus non-Indigenous rugby league match, was an assertion of a clear redefining of the game on distinctly Indigenous terms.

‘I love when Blackfullas win, for the simple fact that we are never meant to win. The odds are always stacked against us to make sure we don’t because the game is rigged by race.’

The winning was less about power over, but the power to be, on our terms, free from those damn indignities. Du Bois speaks of these moments as ‘blue sky moments’ where you beat them in a running race, beat them in an exam or ‘beat their stringy heads’. Those winning moments make it that little bit easier to breathe in a world that is intent on suffocating you, but the labour required to achieve those wins takes its toll too.

Fanon describes the effects of colonial violence upon the colonised as a kind of breathlessness, a breathing that is overserved, occupied, in what he calls ‘combat breathing’. Some days those wins feel like that gasp of air having had to hold one’s breath for so long. It is a gasp of relief. Sometimes, if those wins are big enough or frequent enough, those breaths feel like pure exhilaration and joy, working to reclaim, redeem, or restore the world to how it should be, if only for a moment.

I remember when my husband returned to work the following day at his job with the local council, one of his workmates was surprisingly quiet. Turns out, it was his own workmate who had chosen that moment to tell the world that Black men couldn’t kick, a Dalby local who in that brief outburst declared to the world whose side he really barracks for. My husband didn’t say anything to him; he let him go, much like that moment after he converted.

You see, as we were screaming hysterically, he simply smiled in the direction of the pig pen raising his hand to point and wave to that lone voice. This was a stance not dissimilar to those made by other Black men to racist spectators when gracing sporting fields. I still remember seeing him jog calmly back to his position after the conversion, all the while his head held high. It was a stance I had seen at home too.

—Extract from Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego (UQP, 2021).

Another Day in the Colony

In this collection of deeply insightful and powerful essays, Chelsea Watego examines the ongoing and daily racism faced by First Nations peoples in so-called Australia. Rather than offer yet another account of 'the Aboriginal problem', she theorises a strategy for living in a social world that has only ever imagined Indigenous peoples as destined to die out.

Drawing on her own experiences and observations of the operations of the colony, she exposes the lies that settlers tell about Indigenous people. In refusing such stories, Chelsea tells her own - fierce, personal, sometimes funny...

Announcing the 2022 Stella Prize longlist!

Announcing the 2022 Stella Prize longlist!  Book recommendations from Chelsea Watego!

Book recommendations from Chelsea Watego!  The Best Books of 2021: Non-Fiction

The Best Books of 2021: Non-Fiction

Comments

No comments