Omar Sakr is an Arab-Australian poet, born of Lebanese and Turkish Muslim migrants. The Lost Arabs (University of Queensland Press, 2019) won the 2020 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for Poetry and was shortlisted for the 2020 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, the 2020 John Bray Poetry Award and the 2020 Colin Roderick Award. His poetry has been published in English, Arabic and Spanish, in numerous journals and anthologies. Son of Sin is his first novel.

Today, Omar Sakr is on the blog to answer a few of our questions about his new novel. Read on …

Please tell us about your book, Son of Sin.

OS: Son of Sin is a coming-of-age novel based on my life, in which I try to bring to the page a literary vision of my broke brown boyhood, and show how the people I knew, queer and straight, were doing their best to survive in a hostile place, within families that didn’t know how to love them.

Why was it important to you to write this story?

OS: It’s taken me a long time to get to a position—financially and emotionally—where I was able to look honestly at my life and account for the damages there, the forces that have shaped me into who I am. I have struggled with anxiety and depression for over a decade, and recently was diagnosed with ADHD. I know all too well how many barriers there are to accessing this kind of care, and as with all my work, I write in the hope that I can make the road easier for all the other people in my communities who are struggling; in the hope I can give to them a language, a way of knowing and being, that was previously denied to them. I write in the hope that I can save myself, too.

Your protagonist is a young queer Muslim boy named Jamal Smith. What was your favourite thing about bringing him to life and what was the most challenging?

OS: Ooh. I think my favourite thing has to be letting him be a dumb Leb. This is how I think of myself, mostly with real affection. There’s a certain irreverent and sacred ridiculousness about how we act and talk with each other, and I loved showcasing that. The most challenging part was putting him through some of what I experienced. Despite what I’m sure will be said about this book, I didn’t give to this character all of my pain or all of my trauma, only some. I’m not even sure I’d use that word … one of the impacts of having lived it is a certain desensitization. This was challenging not only in the sense that it hurt to revisit the pain but also because it made me realise on some level I wanted the character to suffer exactly as much as I did. This resentment, this urge to inflict harm, has nothing to do with my purpose as an artist. I had to confront that.

Why do you think that generational sagas of love and trauma still resonate with contemporary writers and readers?

OS: You’ve just described life. That’s all it is—generations of love and trauma.

‘I write in the hope that I can make the road easier for all the other people in my communities who are struggling; in the hope I can give to them a language, a way of knowing and being, that was previously denied to them.’

What was the experience of writing a novel like in comparison to a poetry collection? Do you think that the boundaries of form are more fluid than one might think?

OS: Not really. How you interpret what you read is fluid, the forms are fairly fixed. Though, as with any fixation, fence or boundary, there are those who will subvert, break, or leap over them— blessed be their names.

My experience writing this novel was stressful and difficult for a number of reasons, not least of which is that it occurred during the pandemic. I don’t know that it’s wise to take this as a uniform lesson in prose. What I can say is that I come to poetry with a surety, an innate calm: I swim in it with ease, in part because the end is always in sight. In prose I feel like a flailing fool, the end is everywhere and nowhere. What I liked most about it is also what I hated most—the length! But once you sink far enough into it to forget the present, to create a new kind of dailiness, there comes a certain bliss, which I already miss.

Can you tell us a little bit about your journey towards becoming a writer?

OS: I think I was driven to writing because of all the silences in my life, and in Son of Sin, that’s what I pit Jamal against—all the ways what goes unsaid can damage you.

Your previous poetry collection, The Lost Arabs, won the 2020 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Poetry and was shortlisted for many others. What kind of an impact did that have on your writing career?

OS: It was monumental. It’s the largest prize for poetry in the country, and the money has had a transformational impact. When I talk about being in a position now to reflect honestly, to access medical care and therapy, this is what I mean. It provided a security I’ve never had before. I’m still very much engaged in the healing process, but a large part of these first steps, in life and subsequently in literature through this novel, were enabled because of this award.

What is the last book you read and loved?

OS: Take Care by Eunice Andrada is an extraordinary, staggeringly beautiful collection of poetry. For literary fiction, I would say The Wrong End of the Telescope by Rabih Alammedine. For fun, I would say The Blacktongue Thief by Christopher Buehlman.

What do you hope readers will discover in Son of Sin?

OS: Something new! Something that makes them feel, and think.

And finally, what’s up next for you?

OS: Personally, aside from just struggling to survive this pandemic, along with my wife I am expecting our first child in May, which is the source of a whole new universe of terror and excitement. Professionally, I’m revising my third poetry collection, Non-Essential Work, which is due out next year with University of Queensland Press.

Thanks Omar!

—Son of Sin by Omar Sakr (Affirm Press) is out now.

Son of Sin

An estranged father. An abused and abusive mother. An army of relatives. A tapestry of violence, woven across generations and geographies, from Turkey to Lebanon to Western Sydney.

This is the legacy left to Jamal Smith, a young queer Muslim trying to escape a past in which memory and rumour trace ugly shapes in the dark. When every thread in life constricts instead of connects, how do you find a way to breathe? Torn between faith and fear, gossip and gospel, family and friendship, Jamal must find and test the limits of love...

Bestsellers: Emma Carey continues to perform, Johnny Ruffo and Jane Harper turn heads of readers!

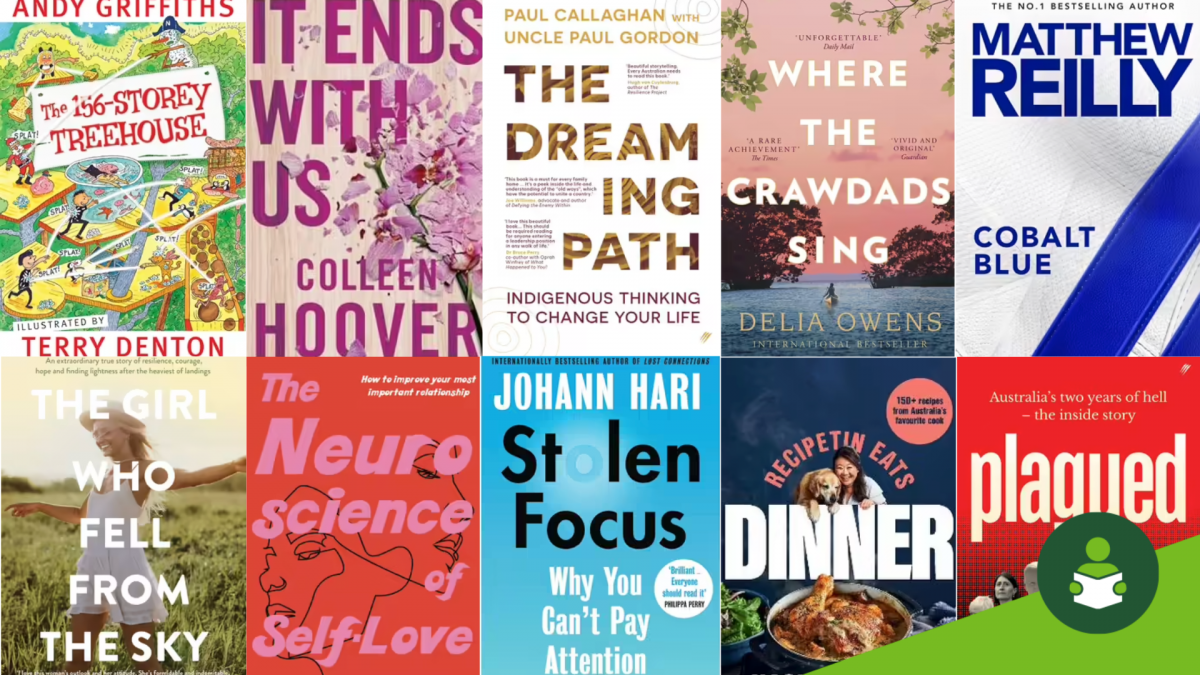

Bestsellers: Emma Carey continues to perform, Johnny Ruffo and Jane Harper turn heads of readers!  Bestsellers: RecipeTin Eats and The 156-Storey Treehouse score highly with readers!

Bestsellers: RecipeTin Eats and The 156-Storey Treehouse score highly with readers!  Ten Terrifying Questions with John Tesarsch

Ten Terrifying Questions with John Tesarsch

Comments

No comments