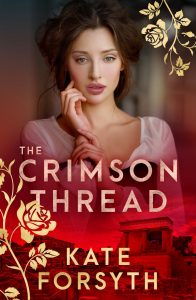

Dr Kate Forsyth is an award-winning author, poet, and storyteller. Her most recent novel is The Crimson Thread, a reimagining of ‘The Minotaur in the Labyrinth’ myth set in Crete during the Nazi invasion and occupation of World War II. Other historical novels include Beauty in Thorns, a reimagining of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ told in the voices of four women of the Pre-Raphaelite circle of artists and poets; The Wild Girl, the story of the forbidden romance behind the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales which was named Most Memorable Love Story of 2013; and Bitter Greens, a retelling of ‘Rapunzel’ which won the 2015 American Library Association award for Best Historical Fiction. Kate’s other books include Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author, co-written by her sister Belinda Murrell, with the assistance of the Nancy Keesing Fellowship. It was longlisted for the 2021 Readings Non-Fiction Prize and the Indie Book Awards. Kate has a BA in literature, a MA in creative writing and a Doctorate of Creative Arts in fairy tale studies, and is also an accredited master storyteller with the Australian Guild of Storytellers. She has taught writing retreats in Australia, Fiji, Greece, and the United Kingdom.

Please tell us a little bit about the myths and ideas that inspired your new novel, The Crimson Thread

The Crimson Thread is a story of love, war, espionage, betrayal & a secret code hidden in embroidery set in Crete during World War II.

I first became interested in Crete when I was a kid and spent a fortnight at my grandparents’ house over the Christmas holidays. It didn’t take me long to read all the books I had packed, and so my grandmother showed me where some old children’s books were kept on a high shelf in a cupboard. I took down two quite at random.

The first was The Chalet Girls in Exile, a story about a group of English schoolgirls in Austria that escaped from the Nazis through the Alps. It was an exciting, fast-paced adventure, and I told my grandparents all about it that night at dinner. My grandfather then told me that my great-uncle had similarly escaped from the invading Nazis through the White Mountains of Crete. He had fought at the Battle of Crete, one of the bloodiest clashes of the war, and then – exhausted, ragged, starving – retreated with thousands of other men over soaring, snow-clad mountains as the Luftwaffe bombed and machine-gunned them ruthlessly. He managed at last to reach a tiny, stony beach on the far side of the mountains, hiding out in a cave to escape the Germans who were hot on their heels. British warships were sent from Egypt to evacuate the ANZAC soldiers, but could only sail at night else they’d be blown up. They had to race to Crete under the cover of darkness, pick up as many men as they could fit, then speed back to safety in Alexandria. Many of the ships were blown up. My great-uncle managed to get away, but around 7,000 Australian and New Zealand soldiers were left behind and became prisoners-of-war in horrific circumstances.

The next day I picked up the second book I had chosen: Tales of the Greek Heroes by Roger Lancelyn Green. I just loved his surname – it sounded so magical! It begins: ‘If ever you are lucky enough to visit the beautiful land of Greece you will find a country haunted by more than three thousand years of history and legend.’ I dived in and for the first time discovered the tales of Prometheus who stole fire from the gods, Perseus the Gorgon-slayer, the labours of Heracles, and – the 14th story in the book – ‘The Adventures of Theseus’, set in the ancient city of Cnossos in Crete.

The myth tells the story of how Ariadne, the daughter of the king of Crete, helps Theseus kill the minotaur. The bull-headed monster is her half-brother but demands the blood sacrifice of seven young men and seven young women every seven years. Ariadne gives Theseus a spool of blood-red thread so that he can find his way through the winding maze, fight the minotaur, and then find his way out again safely. After the minotaur’s death, Ariadne is betrayed and abandoned by Theseus, but she finds new love in the arms of Dionysus, the god of wine and epiphany. He gives her a crown of seven stars, and she sets it in the heavens to guide all who are lost, in the form of the constellation of Corona Borealis. Read so close after hearing the story of the Battle of Crete, ‘The Adventures of Theseus’ fixed the Greek island in my imagination as a place of danger, mystery and wonder.

About forty years later, I was touring with my novel The Blue Rose and visited a small country town. Driving down the main street, I saw an old second-hand bookshop and at once pulled up and went in to explore. I was thrilled to discover a very rare first edition copy of Tanglewood Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne, illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. I had to buy it, even though the price was much more than I could afford.

Tanglewood Tales is a collection of ancient Greek myths, retold in Hawthorne’s beautiful, limpid prose. ‘The Minotaur’ was the seventh book in the tale. As I read: ‘the high, blue mountains of Crete began to show themselves among the far-off clouds’, I remembered my childhood fascination with the island, and the myth, and with Ariadne, ‘a beautiful and tender-hearted maiden (who) wept, indeed, at the idea of how much human happiness would be needlessly thrown away, by giving so many young people, in the first bloom and rose blossom of their lives, to be eaten up” by the minotaur. It seemed to me that this needless sacrifice of young lives was like what happened to so many sent to fight a war.

In a flash, the idea came to me: I wanted to write a novel that reimagined the Minotaur in the Labyrinth myth, set in Crete during World War II.

That was in July 2018. I have spent the past three years deeply immersed in the history and culture of Crete. I have cooked traditional Cretan meals, listened to the melancholy music of the Cretan lyre, read everything I could find about the Nazi invasion and occupation of the island, and explored the island with my family. I’ve studied the history and meaning of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth myth, and filled four notebooks with scribbled notes, maps, photographs, timelines, and examples of secret codes. I even taught myself how to embroider – my heroine Alenka embroiders secret messages on a quilt so she can smuggle messages to the resistance under the very noses of the German officers she is forced to work for. I loved embroidering so much, I am now making my own quilt with my life story encoded in brightly coloured thread.

The story of my great-uncle’s desperate fight and escape over the White Mountains was the first seed for The Crimson Thread. As I wrote my book, however, I discovered my fictional tale had uncanny parallels with the true-life story of Phyllia Akoumianakis, a young woman who grew up next to the ruined palace of Knossos – the mythical home of the minotaur – and who worked for the Wehrmacht and smuggled out classified information for the resistance. She knew all the British officers living in disguise in the lonely mountains of Crete, including the writers Patrick Leigh Fermor, Xan Fielding, and W. Stanley Moss who all wrote fascinating memoirs about their time playing hide-and-seek with the Germans and plotting their overthrow. She even appears as herself in ‘Ill-Met by Moonlight’, the 1954 black-and-white film starring Dirk Bogarde that was based on Billy Moss’s book of the same name. Her bravery, and that of the other Cretan resistance fighters, inspired Winston Churchill to say: “until now we believed that the Greeks fought like heroes. Hereon we shall believe that heroes fight like Greeks.”

Buy it here

The Crimson Thread

Set in Crete during World War II, Alenka, a young woman who fights with the resistance against the brutal Nazi occupation finds herself caught between her traitor of a brother and the man she loves, an undercover agent working for the Allies.

Polin-style book recommendations for fans of Bridgerton Season 3

Polin-style book recommendations for fans of Bridgerton Season 3  What students are reading right now – February 2024

What students are reading right now – February 2024  What do we know about the Boy Swallows Universe Netflix show?

What do we know about the Boy Swallows Universe Netflix show?

Comments

No comments