Therese Spruhan is a Sydney-based photographer, journalist, freelance writer and swimmer who blogs about pools and swimming. Her own experience of swimming at Northbridge Baths in Sydney led her to wonder about the way childhood swimming shapes our views of the world as adults. Her book, The Memory Pool, is a delightful anthology that brings together reflections and recollections about the swimming pools of childhood from a range of Australians, including Trent Dalton, Leah Purcell, Shane Gould, Bryan Brown and Merrick Watts.

Today, you can read an extract from Therese’s chapter of The Memory Pool. Read on!

Embracing the glorious king tide

by Therese Spruhan

My earliest memory of Northbridge Baths is a flash of movement and the colour pink. It is late 1964, and I am four. Mum has just applied pink zinc to my nose and shoulders on the grassed area at the baths where my family always sat when we were little. Then I am running towards the water in my stretchy pale pink one-piece, past my little brother Mark playing with his bucket and spade on the sand, and towards Dad in the olive-green water.

I climb on his back and he takes me out to the deeper part where the water turns a darker emerald. He pretends to be a crocodile about to eat me up and I giggle when he turns his head and opens his mouth as if he is about to take a bite. When we head back to the shallows my older sister Annette has a go on Dad’s back and then Mum joins us in the water, holding my hands and leading me along, encouraging me to blow bubbles and kick. Later, when Mum calls out that it’s time to leave, I duck under again so I will take home the feel of the water and the smell of salt on my skin. Soon after that memory, when I was still four, I went to my first official swimming lessons, but they were at the Lane Cove pool, not Northbridge Baths, and I wasn’t happy. I didn’t like the way the chlorine went down the back of my nose when I floated or attempted to do back-stroke. I was happy the following year when my lessons were back in the salt water at the baths. Each year we did ‘Learn to Swim’ classes and extra ones with Col, the tall, tanned-like-leather manager of the baths, and on 26 January 1968, when I was seven, I was awarded a certificate signed by H Wyndham, the Director-General of the NSW Department of Education, for swimming 30 yards.

Eighteen months later, on the first Saturday in October 1969, Mum drove my sister and brother and me down to the baths to join the Northbridge Amateur Swimming Club. After that, my relationship with the baths became very tied up with the swimming club. For the next 10 years my Saturday morning routine in summer started before 7 a.m. when my sister and I got up, put on our Speedos, T-shirts and a pair of terry-towelling shorts. We’d wrap our towels around our necks and step into thongs and try not to wake our parents as we shut the front door. Then we’d walk around to our neighbours, the Halls, and when our friends Therese and Kathleen emerged we’d head down their side steps and onto Minnamurra Road. From there it was all downhill, and if we were late, we’d run. Halfway along Widgiewa Road, the very steep street that led down to the baths, we’d take a short cut through the bush and emerge in the car park, where a kookaburra would be letting out a loud who, who, ha, ha in one of the twisting pink-orange angophoras as a blue-tongue lizard slithered across our path. Then we’d bound down the steps, hand Col our 20 cents, push through the turnstiles and we were in.

On the concrete area in front of the men’s change rooms, bodies with that just-out-of-bed smell in differ- ent stages of undress would be milling around card tables signing on for the morning’s races. Most Saturdays I entered the 50-metre events in all strokes and on alternate weeks I’d do a 200-metre freestyle or 200-metre medley, and once a year the club held a mile swim which involved 32 laps. After we’d signed on for our races we’d walk around to the deep end to stake out a spot on the bench above the boardwalk. The orange and white lane ropes would be unrolled and attached to eight chrome hooks at the bottom of the blocks at each end of the 50-metre area.

‘Last call for entries,’ would come over the PA as the club organisers made their way around to the deep end with their clipboards.

When my first race was called I’d pull my cap over my head and jump down onto the blocks, which could be quite a leap if the tide was low, and one time I remember I hurt my foot when I landed hard. There was a ladder not far away, but only little kids and older people took that route. When everyone was standing in front of their lane, the starter would call out, ‘On your mark, get set,’ and after the gun went off, he’d count out from one in a loud voice, to sometimes into the 20s, as the races were all handicap events.

It was hard to swim straight in the lanes and often I’d veer too much to the right and my arm would crash into the rope or a jelly blubber. I’d straighten up again and when my hand touched the blocks at the other end, the timekeeper, who would be one of the parents in a floppy hat, old T-shirt and Speedos, would lean down and call out my time. I’d swim under the lane ropes and climb up the chrome ladder shining silver in the sun and re-join my sister and my friends on the bench.

After the races were over and the lane ropes were pulled in, I’d go to the shop and buy my lollies. Col would be standing behind the counter in his navy Speedos that he wore low on his bum and when I’d walk up to the counter he’d say, ‘Yes, Therese.’ Col could never pro- nounce my name the same as everyone else. He always made it rhyme with cerise in a way that made it sound more exotic. ‘Two Redskins, one Spearmint, one Milko, a Raspberry Pop, and a Curl,’ I would say and he’d drop them into a small white paper bag and take my 20 cents.

Then I’d start my journey home, unwrapping one of my Redskins and sucking on it as I trudged back up the very steep Widgiewa Road and wound my way up Minimbah and Minnamurra Roads till I reached our house in Byora Crescent. When I got home, I’d go to my room and lie on my bed. The smell of grass being mowed would waft through my open window and another kookaburra that lived in the huge gum tree next door would laugh. I’d lie back on my bed with my lollies and day-dream, enjoying the blissful feeling in my body after a morning of hard exercise.

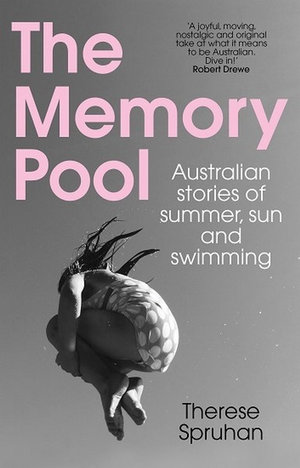

The Memory Pool is out now

The Memory Pool

Australian stories of summer, sun and swimming

Smell the chlorine, taste the hot chips and feel the burning concrete underfoot as you read these stories of Australian childhoods at the pool.

Swimming is a central part of most Australian childhoods. We idealise beaches and surf, but for many kids the local pool – whether it’s an ocean, tidal or a chlorinated pool – is where they pass summer days. Pools are places of imagination, daring, belonging, freedom, friendship and romance. For some they are places of hard-core swimming training...

Read an extract from Abracadabra by Robert Dessaix!

Read an extract from Abracadabra by Robert Dessaix!  What’s it like to be chased by a cassowary? Let Felicity Lewis tell you …

What’s it like to be chased by a cassowary? Let Felicity Lewis tell you …

Comments

November 21, 2019 at 3:31 pm

What a great read! Each story is different and … SO summer growing up at a pool, ANY pool!