At a Glance

800 Pages

5.2 x 12.9 x 19.9

Paperback

$26.99

or 4 interest-free payments of $6.75 with

Ships in 3 to 5 business days

Jack McKenzie is a harmonica player, soldier, dreamer and small-time professional fisherman from a tiny island in Bass Strait. Nicole Lenoir-Jourdan is a strong-willed woman hiding from an ambiguous past in Shanghai. Larger than life, Private Jimmy Oldcorn was once a street kid and leader of a New York gang. Together, they reap a vast and not always legitimate fortune from the sea.

Spanning eighty years and four continents, Brother Fish is an inspiring human drama of three lives brought together and changed forever by the extraordinary events of recent history. But most of all it is about the power of friendship and love.

'It is a big, racy read that covers not just Australia, but China, Korea and America … underpinned with impressive historical research.' The Age

'Triads, the yakuza, Bass Strait storms – Courtenay packs it all in as he layers tragedy and triumph in almost equal measure.' Sydney Morning Herald

About the Author

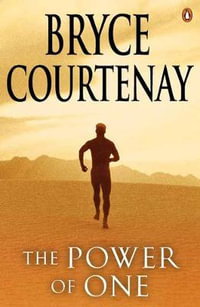

Bryce Courtenay was born in South Africa and has lived in Sydney for the major part of his life. He is the bestselling author of The Power of One, April Fool's Day, The Potato Factory, Tommo & Hawk, Jessica, Smoky Joe's Cafe, Four Fires, Whitethorn and Brother Fish.

The Anzac Hotel – Launceston, 1986

I'm standing at the Gallipoli Bar waiting to meet Jimmy Oldcorn in the Anzac Hotel in Launceston. Jimmy and I meet in this particular pub on the 9th of August every year regardless of where we happen to be in the world. It is a tradition that goes back a long, long way to a cold and bitter war most Australians have forgotten. Thirty-four years ago I invited Jimmy home with me from Korea – for he was a Yank with no place in his native country he could remember with sufficient affection to wish to return.

Jimmy and I had been taken prisoners of war and had spent almost two years in various establishments initially under the North Koreans, and subsequently the Chinese. We'd both been wounded, though not in the same battle, and each had a leg badly broken when we'd been captured. Even the best part of two years into captivity, with the bones knitted, our bad legs still gave us a fair amount of pain. Close to the time of the cease-fire and armistice, we'd been released in a prisoner-of-war exchange with the Chinese and were subsequently taken to US 121 Medical Evacuation Hospital in Seoul for assessment of our injuries. Here they gave us the good news and the bad news. The bad was that, in both our cases, they would need to break the crookedly knitted leg and reset it. The good news, for me anyway, was that the comfort bag the Red Cross gave me included a large bar of chocolate.

Compared to the bad, the good news must sound pretty trivial. But it just goes to show, even in extremely emotional moments, life often comes down to trivial things. This simple gift of chocolate was a symbol of great importance to me. Asians don't eat chocolate – it is not a taste they've acquired. On the other hand, for a poor Australian kid growing up in the Great Depression and the lean years that immediately followed, chocolate was the ultimate luxury. As a prisoner of war it had come to represent all that was good about our way of life. When the pain and the beatings became really bad I'd dream of tasting chocolate just one more time before I died, although I knew the likelihood of this happening was extremely remote. A prisoner of war with a broken leg and multiple wounds had virtually no chance of surviving the primitive conditions of a North Korean field hospital. When we did survive the various field hospitals, the POW camp that followed promised to finish us off. Now, almost miraculously, we'd made it! Here I was, the personal possessor of a bar of milk chocolate and safely ensconced in a military hospital bed, a fair-dinkum bed with springs that squeaked, all sixty-five pounds of skin and bone concealed beneath crispy white sheets.

With trembling hands I tore away the top quarter of the outer wrapper, peeled the silver foil from a corner of the chocolate bar then carefully broke off an individual square. Then, postponing the grand moment when it would contact my tongue so as to better anticipate the experience, I examined the brand name pressed into the tiny portion. Its calligraphy, so precise and assured, belonged to a world where sanity and order always prevailed. At last the warmth from my finger and thumb began to transfer into the tiny square and it started to soften, so I placed the chocolate in my mouth, closing my eyes to savour its exquisite creaminess. The initial flavour was everything I'd dreamed about. Then, after a few seconds the richness hit my stomach. It was as if I had been punched in the solar plexus, causing me to double over in the bed so that my head slammed against my knees. This was followed by an irrepressible surge which rose from my lower regions and threw me backwards. I started to retch when, just as suddenly, my torso was hurled forward, sending a spray of watery vomit over the snowy sheets. The unfamiliar chocolate had been too much for a stomach accustomed to a diet of boiled millet and thin rice gruel. I had come full circle, back to an experience that began on the night I was taken prisoner by the North Koreans.

On the night of my capture I had been dragged unconscious from the snow into a partially demolished hut. I awoke in great pain, and pleaded with my captors to fashion some sort of splint to support my shattered leg. While they nodded their heads acknowledging that they could see my leg was broken, they seemed unconcerned. They spoke no English and seemed more interested in going through my pack than attending to my condition. Soon enough one of them came across a small bar of army-issue chocolate, and after removing the wrapper seemed not to know what to do next. Thinking it might be a good way to ingratiate myself I attempted a smile and indicated, by bringing my fingers to my mouth and making a chewing then swallowing motion, that he should eat it. The soldier broke off a square and placed it into his mouth. Instead of allowing the chocolate to melt on his tongue, he did as I had indicated and chewed, then immediately swallowed. I waited for the look of delight to cross his face. To the enormous amusement of the others, his face screwed into a grimace of disgust and he began to spit furiously. Bent double and clutching his stomach he started to heave, and then vomited over his canvas boots. His comrades, delighted at the practical joke I'd played on him, were convulsed with laughter, congratulating me with their looks and smiles. When the soldier finally recovered, I could see he was furious. I had caused him to lose face in front of his mates. He advanced on me and, without warning, snatched up his rifle and smashed the butt into the side of my jaw, breaking several teeth. I had just discovered the hard way that chocolate wasn't an Asian thing.

From the Evacuation Hospital in Seoul, after the briefest of goodbyes, Jimmy was evacuated to the Tokyo Army Hospital while I was to go to the British Commonwealth Hospital in Kure, the port we'd departed from when we'd first embarked for Korea.

At Iwakuni Airport the Red Cross had put on a posh meal for the Commonwealth prisoners before we were to board an ambulance train to the military hospital. As demonstrated by the chocolate episode, my stomach wasn't yet ready for such a generous gesture. All I could eat was a couple of forkfuls of vegies, using my paper napkin to wipe the glaze of butter off the baby carrots, although, as a special treat, I took a chance with two dessertspoons of mixed-fruit jelly . . .

After three and a half months in hospital the authorities took the opportunity to bum a ride for a dozen or so of the Australian walking wounded, myself included, on a chartered Qantas flight taking some of the military top brass back to Melbourne.

It was decided that I would do a further three months' convalescence in Australia before being discharged from the army. With my left leg in plaster up to the hip I was still very much dependent on my crutches, and it had taken a fair bit of persuasion on my part to convince the army doctors to let me go home. Crutches notwithstanding, I was going back to the island – the war was over for me. Before leaving Japan I'd been given two years' back pay and a couple of medals to wear on Anzac Day. It was more money than I'd ever possessed in my life, and I got scared just thinking about it.

The arrangement was that I was to remain in Melbourne to await Jimmy's plane from Tokyo due in two days' time. How he'd persuaded the US military to let him do his convalescence in Australia I'll never know, except that Jimmy could persuade most people to do most things.

Jimmy Oldcorn's reason for being with me in Melbourne began in a North Korean field hospital situated in a cave somewhere deep in the mountains that form the inhospitable spine of the Korean peninsula. We'd been chatting together, me talking of home and the island in an attempt to forget our miserable surroundings, when suddenly the idea struck me. 'Hey, Jimmy, when this is all over why don't you come home with me, mate?' I'd repeated the offer on several occasions and did so again when our release looked like being a real possibility, though on that occasion I was quick to add, 'Mind you, you'll probably go a bit stir-crazy, there's bugger-all to do except lie in the sun, fish, surf, dive for crayfish or go duck or roo shooting. But my mum cooks real good cray stew.' Sounds funny today, but at the time the qualification wasn't intended to paint a picture of halcyon days spent on an idyllic island. I honestly felt the need to warn him in advance that things were pretty slow-moving back home.

But, of course, he took it to mean an invitation to paradise. He'd tut-tut and shake his head. 'I don't know, Brother Fish, that I can endure such hardship. It ain't easy when you're accustomed as I is to da cos-mo-pol-itan life of Noo York city, man!'

We were both badly wounded and slowly rotting in the freezing, stinking, dark, wet, dirty, overcrowded cave that passed for a North Korean field hospital. While he always agreed to come, adding some amusing protest such as the one above, we knew it was just talk, a way of bolstering our despairing spirits. We both had badly broken left legs that hadn't set well and our wounds in several other places were infected and suppurating under the now filthy bandages we'd applied ourselves, mine being a couple of field dressings every Australian soldier carries and Jimmy's from the first-aid pouch the Yanks carried. We fully expected to be shot, as the Korean soldiers, used by the Japanese as POW guards during World War II, had a well-documented reputation for senseless brutality. In the chaotic early stage of the war, they were known to shoot their captured wounded. I guess we were lucky – they certainly weren't the friendliest mob, and why they hadn't put a bullet through our heads and put us out of our misery was a complete mystery. Nevertheless, they seemed determined to let the consequences of neglect do the job for them. We were clearly not intended to come out of the cave alive.

By the time we were transferred to the POW camp, the bond formed between Jimmy Oldcorn and myself had grown very strong. I had come to trust him like a brother. More than this he was my mate and, in the arcane and inarticulate way Australian males have of expressing their emotions, your mate is for life, come hell or high water.

This is how we might have been described when we first joined our respective armies. In the red corner, Jack McKenzie, K Force, 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), five-feet five-inches in his size-six army boots. In appearance all sinew and bone, wearing a blaze of copper-coloured hair, deeply freckled and, at twenty-five, already irreparably sun-damaged. Fighting weight, 125 pounds when fully fit.

In the blue corner, Jimmy Pentecost Oldcorn, 24th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, American Negro, six-feet six-inches in his khaki army-issue socks, weighing in at 260 pounds of solid muscle with fists the size of soup plates.

This was not how we looked when we departed from the hell of the North Korean hospital cave and were handed over to the Chinese. Despite losing a mountain of weight Jimmy remained a big man, around 180 pounds. While I, reduced to sixty-five pounds in total, could have been knocked off my feet by a healthy sneeze.

Jimmy was the colour of bloodwood honey, which at the time was disparagingly known in America as 'high yella', while I came from a long line of redheads who seem to have been born minus a layer of skin. His hair, grown long in prison camp, would at a later time become fashionable and be referred to as the 'Afro', while his dark beard sat naturally and evenly attached to his jowl and chin as if carefully worked up by a clever make-up artist. By contrast, I carried several months of uncut, filthy, matted red hair and a ragged beard, both crawling with vermin. I must have looked like one of those long-limbed Indonesian ginger-coloured apes. What are they called – orang-utans!

Even when we'd been liberated and cleaned up, the disparities between us remained. We were both emaciated, heads shaved, eyes over-bright and set into deep dark sockets, the difference being that he still looked like a Nubian prince while my hollow, bruised-eyed appearance and pale, almost translucent skin speckled with a firmament of ginger freckles suggested that I'd been subjected to several bouts of chemotherapy long after I should have been mercifully left to die.

I'm not sure what it takes for two blokes to become the sort of mates who will willingly die for each other. It can't simply have been gratitude. Jimmy had little reason to feel grateful to me and while he had undoubtedly saved me on more than one occasion from throwing in the towel, he'd done the same for the American prisoners. Yet, apparently they didn't feel the same way about him. I asked him on one occasion whether they'd come to see him in the Tokyo hospital to which they'd all been taken. Jimmy just laughed. 'Ain't like dat, Brother Fish, in Uncle Sam's mil-it-tary. Coloured soldier do a white soldier a goodly deed, pick him up when he fall down, dat white guy he gonna hope his friends ain't lookin' on, man.' It seemed that not one of the Americans he'd helped pull through had come to thank him.

My family were fisherfolk and when I was a kid on the island, 'fisherman' was very close to being a dirty word. Fishermen were on the bottom rung, and the sea was one of the last frontiers where you could hunt for food you didn't need to pay for. Access to the sea is free to those willing to take the risks involved. The way things were, we seemed never to have fully recovered from the Great Depression. There wasn't a lot of work about other than on a fishing trawler or a cray boat – a hard, dirty and dangerous way to make a crust. The interior of the island's Anglican and Catholic churches boasted almost as many memorial plaques carrying the names of fishermen who had disappeared at sea as there were headstones in the churchyard.

Queen Island, set slap bang in the middle of Bass Strait, is subject to sea mists and furious gales, and over the past hundred years many a sailing ship has been wrecked on our notoriously dangerous coastline. The small fishing craft that met their end smashed against the reefs and cliffs or lost in a sudden storm were simply too numerous to count. Everyone knew fishing was a mug's game, nevertheless it was the only game in town a poor family could play.

In those post-Depression years most Australian working-class parents dreamed of their sons growing up to be something a little better. On the island this hope was simply defined in a mother's prayer: 'Dear God, please don't let him grow up to be a fisherman!' If you couldn't read or write you could always work on a fishing boat. As a fair number of men on the island fell into this category, including my old man, the cruel sea was how we scraped a precarious and always dangerous living.

Alf, my old man, was a rough sort of cove, what some might call an ignorant man. But if he couldn't read or write he wasn't a whinger or in the least resentful of those who may have been considered more fortunate than him. He'd give you the shirt off his back if you needed it and he'd always provided for his family. Even during the Great Depression when he couldn't get work on a trawler he'd go out in a skiff and set craypots or bring home a snapper or a couple of bream. Our clothes were made on the faithful table-top Singer from the same sugar bags we used as towels, but I can honestly say Alf saw to it that we never went hungry. He was as honest as the day is long, even though honesty wasn't a virtue much discussed on the island – it was simply taken for granted that people didn't steal from each other, and crime against property was thought to be something that happened on the mainland or the big island where people thought they were better than us but whom we knew were a bunch of crooks and shysters, or as my mum would say, 'People who'll steal the wax out of your ears to make communion candles'.

That was the curious thing: while, like us, most of the island's inhabitants came from convict stock who'd moved in from Tasmania in 1888, there was virtually no 'conventional' crime on the island. When we were kids the community did have a policeman who carried the grand title 'Bailiff of Crown Land and Inspector of Stock' but whom we all knew as 'The Trooper', who got just as pissed as everyone else of a Saturday night. But if you wanted some documentation done that concerned the law you went to see Nicole Lenoir-Jourdan, the bossy-boots librarian and local piano teacher, who also acted as justice of the peace and who somehow managed to scare every schoolkid on the island and not a few of the dimmer adults into believing that she had infinitely more power than any policeman when it came to matters of upholding the sanctity of the law.

The words 'justice' and 'peace' were a powerful combination that came together in our imagination to mean that if there was no peace, then the justice meted out by Miss Lenoir-Jourdan would see it soon restored, with dire consequences for the bloke who'd had the temerity to disturb it. While there appeared to be no immediate evidence that the offender had been punished, we kids sensed this was done in such a deep and covert manner that the offender would carry the inward scars for life and never again dare to repeat the offence. Little did I know at the time that this fearsome justice of the peace was going to have a large influence on my life.

ISBN: 9780143002703

ISBN-10: 0143002708

Published: 1st January 2006

Format: Paperback

Language: English

Number of Pages: 800

Audience: General Adult

Publisher: Penguin Australia Pty Ltd

Country of Publication: AU

Edition Number: 1

Dimensions (cm): 5.2 x 12.9 x 19.9

Weight (kg): 0.68

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

Orders over $79.00 qualify for free shipping.

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.