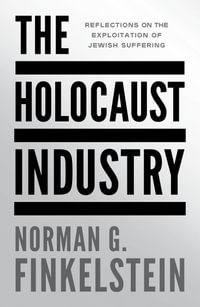

At a Glance

Hardcover

$176.00

or

Ships in 7 to 10 business days

ISBN: 9781839987311

ISBN-10: 1839987316

Published: 8th April 2025

Format: Hardcover

Language: English

Number of Pages: 256

Audience: Professional and Scholarly

Publisher: Anthem Press

Country of Publication: GB

Dimensions (cm): 22.9 x 15.3 x 2.5

Weight (kg): 0.51

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

Orders over $79.00 qualify for free shipping.

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.

You Can Find This Book In

This product is categorised by

- Non-FictionHistorySpecific Events & Topics in HistoryGeonocide & Ethnic CleansingThe Holocaust

- Non-FictionHistoryMilitary History

- Non-FictionWarfare & DefenceOther Warfare & Defence IssuesWar Crimes

- Non-FictionSociety & CultureSocial Issues & ProcessesSocial Discrimination & Inequality

- Non-FictionSociety & CultureSocial GroupsEthnic StudiesEthnic Minorities & Multicultural Studies