At a Glance

Paperback

384 Pages

384 Pages

Dimensions(cm)

2.9 x 12.9 x 19.8

2.9 x 12.9 x 19.8

Paperback

RRP $24.95

$23.75

or 4 interest-free payments of $5.94 with

In Stock and Aims to ship in 1-2 business days

When will this arrive by?

Mrs Moses is a small woman with a big heart and enormous courage.

The only survivor of a Cossack raid on her village, she takes with her a big cast-iron frying pan, so heavy that she can only sling it over her back. Yet this is no ordinary frying pan – it's the Family Frying Pan, blessed with a Russian soul.

From this frying pan Mrs Moses manages to feed the various refugees who are travelling with her across Russia to freedom. In return, each of the group must tell a story around the campfire at night – stories of compassion and bravery, of human frailty and, above all, of hope.

The Family Frying Pan is Bryce Courtenay at his storytelling best.

'It comes from inside Courtenay's soul, which is the soul of a storyteller and a pilgrim … Get out the tissues.' Sydney Morning Herald

About the Author

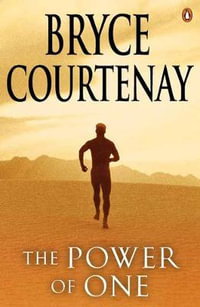

Bryce Courtenay was born in South Africa and has lived in Sydney for the major part of his life. He is the bestselling author of The Power of One, April Fool's Day, The Potato Factory, Tommo & Hawk, Jessica, Smoky Joe's Cafe, Four Fires, Whitethorn and Brother Fish.

The only survivor of a Cossack raid on her village, she takes with her a big cast-iron frying pan, so heavy that she can only sling it over her back. Yet this is no ordinary frying pan – it's the Family Frying Pan, blessed with a Russian soul.

From this frying pan Mrs Moses manages to feed the various refugees who are travelling with her across Russia to freedom. In return, each of the group must tell a story around the campfire at night – stories of compassion and bravery, of human frailty and, above all, of hope.

The Family Frying Pan is Bryce Courtenay at his storytelling best.

'It comes from inside Courtenay's soul, which is the soul of a storyteller and a pilgrim … Get out the tissues.' Sydney Morning Herald

About the Author

Bryce Courtenay was born in South Africa and has lived in Sydney for the major part of his life. He is the bestselling author of The Power of One, April Fool's Day, The Potato Factory, Tommo & Hawk, Jessica, Smoky Joe's Cafe, Four Fires, Whitethorn and Brother Fish.

INTRODUCTION

When I married into my wife's family I inherited her grandmother, Mrs Moses. That's what she was called by everyone in the family, not mama, or mum or nana or buba or even grandmother, simply Mrs Moses. My in-laws referred to her in this way and even addressed her as Mrs Moses. Her first name was Sarah, though she'd been Mrs Moses for so long I doubt whether her own daughter remembered her name. There was nothing cold or formal about this appellation, nor was it intended as a sign of respect. Mrs Moses simply couldn't be called by any other name and still remain herself. From the age of sixteen and unmarried, she had been known as Mrs Moses and it had been ever thus. How this all came about is a part of her story.

Mrs Moses was a famous identity around Bondi Beach. Every sunrise of the year, except for those which occurred on a Friday, would find her ploughing across the sand in her droopy black old-lady bathing suit heading for the surf. Pelting rain, gale-force winds fierce enough to bowl her over, as they often did, waves crashing down, throwing spume and angry spray at the shoreline, it made no difference. At dawn Mrs Moses was ready to bathe.

When, on occasion, the beach was too dangerous for swimming, the king tides smashing against the sea wall, she'd use the handle of her walking stick to knock on the door of the Bondi Lifesavers Club until someone forced it open against the wind and the rain.

'You call this weather!' she'd sniff, shaking a tiny bony finger at whoever appeared. 'From weather you know nothing, young man, in Russia is weather, here is only a bit of raining and winds, now you must open the beach at once so I can bathe!'

Mrs Moses also gathered people like a farm girl might gather eggs, stepping out every morning with an empty basket and returning with it full of new-made friends.

'You got a name?' she'd say, walking directly up to an early morning bather or stroller. 'So tell me, already? Maybe I remember so next time you're not such a stranger. Me, I'm Mrs Moses.' She'd stretch out her tiny claw, 'Pleased to meetcha, Mr Big Nose. Name please?' she'd demand again.

It was her special trick. Well into her eighties (how well she wouldn't say), she never forgot a name, first name or surname. Forever afterwards she'd pass someone to whom she'd introduced herself and say, 'Such a nice morning, Mr Big Nose, Peter Pollock, or Miss Nice Legs, Julie McIntosh, or Mrs Big Boobies, Tania Walker, or Mr Noddy Ears, Eddie Perrini, or Mrs Fat Bum, Sarah Jacobs.' She would greet each with such a disarming smile that it became impossible to take exception.

On her return from her early morning dip in the surf, she'd stop at the skateboard ramp and demand that the action cease immediately, 'Stop, already!' she'd shout, rapping her walking stick against the side of the wooden ramp. Whereupon she would distribute a five-cent piece to every kid on the ramp, 'Go buy a nice ice-cream,' she'd say, 'enjoy, compliments Mrs Moses.'

The skateboarders happily accepted the tiny silver coins and thanked her politely, no one daring to tell her that a single vanilla cone now cost a dollar. In fact, if she ran short, as she often did at times during the school holidays, there' d be a real look of disappointment on the faces of the non-recipients of her largesse. The five-cent coin from Mrs Moses became a status symbol for the skateboarders, to be collected and kept in the pocket of their board shorts to jingle during a tricky turn or backward somersault. Larry Hinds, the Bondi boy who became world skateboard champion, jingled his way to the title with a pocketful of her ice-cream coins. When he returned to Australia he presented Mrs Moses with his world championship T-shirt, which she wore ever after as her nightgown.

Mrs Moses claimed to be five feet and two inches tall though towards the end of her life she was probably under five feet. Nevertheless she stood straight as a pencil and, except for a bit of a pot on her oldlady stomach, she was in pretty good shape.

'From sixteen years and now eighty years and something — don't-ask-it's-none-of-your-business — and still only thirty-five kilos,' she'd say, patting her tummy lovingly. 'Eat once every day only a little.' She'd cup her hand, indicating the amount.'The greedy die young, it's God's revenge for not sharing the food with others.'

When her granddaughter brought me home to introduce me to her family, my future mother- and father-in-law were concerned that the boy their only daughter announced she was going to marry was not Jewish nor seemed to have any real qualifications and even fewer prospects. 'A writer already. How can a writer make money in Australia?' my mum-in-law-to-be protested. Like all Jewish mothers, she was hoping at the very least for a doctor or a lawyer.

However, Mrs Moses had no such concerns, she accepted me immediately, mostly because I was a storyteller and in her mind there existed no higher status. I was soon to learn that in the storytelling department I was a rank amateur compared to her.

Friday evenings it was compulsory to attend family dinner to celebrate the onset of Shabbat, the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath. Despite the prayers, candles and truly awful wine, nothing could have kept me away. Mrs Moses made the best Friday fried fish in the whole of the universe.

I recall on one occasion sitting with the old lady on the back verandah under the bougainvillea enjoying a glass of her homemade ginger beer. Two rosellas were yapping away in the mass of deep scarlet blossom above our heads, the southerly had just blown in across the beach, bringing with it a cooling down after a long hot day. Mrs Moses had cooked the fish earlier in the day but its delicious smell still pervaded the back porch. Even then I fancied myself as a bit of a cook and so I asked her, 'Mrs Moses, how come your fried fish is the best I've ever tasted? What's the big secret? Is it that you always use snapper? Or is it the batter?'

She'd fry it in a light beer batter, snapper caught that morning and bought straight from the Doyles' fishing boat. The fish was the reason she never got to the beach of a Friday. Instead she'd be up at dawn in time to catch the first bus into Bondi Junction to connect with the one to Watsons Bay, arriving to greet the Doyles' fishing boat coming into the pier soon after sunrise.

Always first in the queue she'd inspect the catch with a wary eye and finally choose a big snapper, keeping a beady eye on the scale as it was weighed and then immediately protesting at the price, demanding that she pay the same per pound as she'd paid their father thirty years before. 'Shame on you! Your father should turn in his grave, he should know what you're charging me!'

With a suitable amount of objection and a collective show of consternation, all of this accompanied by much sighing and shaking of heads, the Doyle brothers finally gave in, the same fishbargaining ritual of every Friday morning of their lives played out. They had long learnt that the first snapper they hauled in every Friday was for Mrs Moses and that it was going to cost them money. Irish, and therefore superstitious, they'd come to think of her fish as a sort of tithe to the sea and, like the skateboarders, they saw Mrs Moses as an essential part of their good luck.

The old lady would carry her catch home on a repeat of the double bus trip, the great fish with its body loosely wrapped in newspaper, the exposed head and tail spilling over the edges of her wicker basket. The bus conductor would step down onto the pavement at the Watsons Bay terminus, take up the basket and place it on a vacant seat next to the window, then he'd open the window. 'Fresh fish don't smell from nothing!' Mrs Moses would snap, 'For your breath we should open a window, this fish I can kiss!'

'I should charge you double, Mrs Moses, that fish takes up more room than you do.'

'All day walking up and down, "Fares please, fares please", this is a job for a nice boy? Double? You want to charge double!' She held up one hand with fingers splayed and the thumb showing from the other. 'The fare has gone up six times since I come first here sixty-five years ago. What we got here, Mr Fares Please, Tommy Johnson, is daylight robbery, no less. Maybe I write to the Prime Minister!'

She'd be home before nine when she'd clean and fillet the large fish, saving the head and the tail for fish soup (also unequalled), and then, well before noon, she'd have completed frying the great white flaky fillets in a golden batter so that they were presented cold for the evening meal, and served with red-rimmed Spanish onion rings and pickled cucumber doused in a sharp brown vinegar sauce.

'The snapper? You think it's the snapper? Snapper, batter! A fish is a fish, Batter also. Flour and egg is flour and egg. A little beer added maybe, salt. I tell you somethink.' She leaned her head slightly towards me and crooked her finger, indicating I should come closer. 'It's The Family Frying Pan!' She said it reverently and like that was its proper name, The Family Frying Pan, in capital letters. Then she whispered, 'It has a Russian soul.' She turned and looked at me, 'One day after I die you will write the story, please. Maybe a whole book.'

'The story?' I asked, not knowing quite what she meant.

'The story of The Family Frying Pan.' She drew back, her eyes suddenly misty, 'My story, I have told no one, only now you.'

When I married into my wife's family I inherited her grandmother, Mrs Moses. That's what she was called by everyone in the family, not mama, or mum or nana or buba or even grandmother, simply Mrs Moses. My in-laws referred to her in this way and even addressed her as Mrs Moses. Her first name was Sarah, though she'd been Mrs Moses for so long I doubt whether her own daughter remembered her name. There was nothing cold or formal about this appellation, nor was it intended as a sign of respect. Mrs Moses simply couldn't be called by any other name and still remain herself. From the age of sixteen and unmarried, she had been known as Mrs Moses and it had been ever thus. How this all came about is a part of her story.

Mrs Moses was a famous identity around Bondi Beach. Every sunrise of the year, except for those which occurred on a Friday, would find her ploughing across the sand in her droopy black old-lady bathing suit heading for the surf. Pelting rain, gale-force winds fierce enough to bowl her over, as they often did, waves crashing down, throwing spume and angry spray at the shoreline, it made no difference. At dawn Mrs Moses was ready to bathe.

When, on occasion, the beach was too dangerous for swimming, the king tides smashing against the sea wall, she'd use the handle of her walking stick to knock on the door of the Bondi Lifesavers Club until someone forced it open against the wind and the rain.

'You call this weather!' she'd sniff, shaking a tiny bony finger at whoever appeared. 'From weather you know nothing, young man, in Russia is weather, here is only a bit of raining and winds, now you must open the beach at once so I can bathe!'

Mrs Moses also gathered people like a farm girl might gather eggs, stepping out every morning with an empty basket and returning with it full of new-made friends.

'You got a name?' she'd say, walking directly up to an early morning bather or stroller. 'So tell me, already? Maybe I remember so next time you're not such a stranger. Me, I'm Mrs Moses.' She'd stretch out her tiny claw, 'Pleased to meetcha, Mr Big Nose. Name please?' she'd demand again.

It was her special trick. Well into her eighties (how well she wouldn't say), she never forgot a name, first name or surname. Forever afterwards she'd pass someone to whom she'd introduced herself and say, 'Such a nice morning, Mr Big Nose, Peter Pollock, or Miss Nice Legs, Julie McIntosh, or Mrs Big Boobies, Tania Walker, or Mr Noddy Ears, Eddie Perrini, or Mrs Fat Bum, Sarah Jacobs.' She would greet each with such a disarming smile that it became impossible to take exception.

On her return from her early morning dip in the surf, she'd stop at the skateboard ramp and demand that the action cease immediately, 'Stop, already!' she'd shout, rapping her walking stick against the side of the wooden ramp. Whereupon she would distribute a five-cent piece to every kid on the ramp, 'Go buy a nice ice-cream,' she'd say, 'enjoy, compliments Mrs Moses.'

The skateboarders happily accepted the tiny silver coins and thanked her politely, no one daring to tell her that a single vanilla cone now cost a dollar. In fact, if she ran short, as she often did at times during the school holidays, there' d be a real look of disappointment on the faces of the non-recipients of her largesse. The five-cent coin from Mrs Moses became a status symbol for the skateboarders, to be collected and kept in the pocket of their board shorts to jingle during a tricky turn or backward somersault. Larry Hinds, the Bondi boy who became world skateboard champion, jingled his way to the title with a pocketful of her ice-cream coins. When he returned to Australia he presented Mrs Moses with his world championship T-shirt, which she wore ever after as her nightgown.

Mrs Moses claimed to be five feet and two inches tall though towards the end of her life she was probably under five feet. Nevertheless she stood straight as a pencil and, except for a bit of a pot on her oldlady stomach, she was in pretty good shape.

'From sixteen years and now eighty years and something — don't-ask-it's-none-of-your-business — and still only thirty-five kilos,' she'd say, patting her tummy lovingly. 'Eat once every day only a little.' She'd cup her hand, indicating the amount.'The greedy die young, it's God's revenge for not sharing the food with others.'

When her granddaughter brought me home to introduce me to her family, my future mother- and father-in-law were concerned that the boy their only daughter announced she was going to marry was not Jewish nor seemed to have any real qualifications and even fewer prospects. 'A writer already. How can a writer make money in Australia?' my mum-in-law-to-be protested. Like all Jewish mothers, she was hoping at the very least for a doctor or a lawyer.

However, Mrs Moses had no such concerns, she accepted me immediately, mostly because I was a storyteller and in her mind there existed no higher status. I was soon to learn that in the storytelling department I was a rank amateur compared to her.

Friday evenings it was compulsory to attend family dinner to celebrate the onset of Shabbat, the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath. Despite the prayers, candles and truly awful wine, nothing could have kept me away. Mrs Moses made the best Friday fried fish in the whole of the universe.

I recall on one occasion sitting with the old lady on the back verandah under the bougainvillea enjoying a glass of her homemade ginger beer. Two rosellas were yapping away in the mass of deep scarlet blossom above our heads, the southerly had just blown in across the beach, bringing with it a cooling down after a long hot day. Mrs Moses had cooked the fish earlier in the day but its delicious smell still pervaded the back porch. Even then I fancied myself as a bit of a cook and so I asked her, 'Mrs Moses, how come your fried fish is the best I've ever tasted? What's the big secret? Is it that you always use snapper? Or is it the batter?'

She'd fry it in a light beer batter, snapper caught that morning and bought straight from the Doyles' fishing boat. The fish was the reason she never got to the beach of a Friday. Instead she'd be up at dawn in time to catch the first bus into Bondi Junction to connect with the one to Watsons Bay, arriving to greet the Doyles' fishing boat coming into the pier soon after sunrise.

Always first in the queue she'd inspect the catch with a wary eye and finally choose a big snapper, keeping a beady eye on the scale as it was weighed and then immediately protesting at the price, demanding that she pay the same per pound as she'd paid their father thirty years before. 'Shame on you! Your father should turn in his grave, he should know what you're charging me!'

With a suitable amount of objection and a collective show of consternation, all of this accompanied by much sighing and shaking of heads, the Doyle brothers finally gave in, the same fishbargaining ritual of every Friday morning of their lives played out. They had long learnt that the first snapper they hauled in every Friday was for Mrs Moses and that it was going to cost them money. Irish, and therefore superstitious, they'd come to think of her fish as a sort of tithe to the sea and, like the skateboarders, they saw Mrs Moses as an essential part of their good luck.

The old lady would carry her catch home on a repeat of the double bus trip, the great fish with its body loosely wrapped in newspaper, the exposed head and tail spilling over the edges of her wicker basket. The bus conductor would step down onto the pavement at the Watsons Bay terminus, take up the basket and place it on a vacant seat next to the window, then he'd open the window. 'Fresh fish don't smell from nothing!' Mrs Moses would snap, 'For your breath we should open a window, this fish I can kiss!'

'I should charge you double, Mrs Moses, that fish takes up more room than you do.'

'All day walking up and down, "Fares please, fares please", this is a job for a nice boy? Double? You want to charge double!' She held up one hand with fingers splayed and the thumb showing from the other. 'The fare has gone up six times since I come first here sixty-five years ago. What we got here, Mr Fares Please, Tommy Johnson, is daylight robbery, no less. Maybe I write to the Prime Minister!'

She'd be home before nine when she'd clean and fillet the large fish, saving the head and the tail for fish soup (also unequalled), and then, well before noon, she'd have completed frying the great white flaky fillets in a golden batter so that they were presented cold for the evening meal, and served with red-rimmed Spanish onion rings and pickled cucumber doused in a sharp brown vinegar sauce.

'The snapper? You think it's the snapper? Snapper, batter! A fish is a fish, Batter also. Flour and egg is flour and egg. A little beer added maybe, salt. I tell you somethink.' She leaned her head slightly towards me and crooked her finger, indicating I should come closer. 'It's The Family Frying Pan!' She said it reverently and like that was its proper name, The Family Frying Pan, in capital letters. Then she whispered, 'It has a Russian soul.' She turned and looked at me, 'One day after I die you will write the story, please. Maybe a whole book.'

'The story?' I asked, not knowing quite what she meant.

'The story of The Family Frying Pan.' She drew back, her eyes suddenly misty, 'My story, I have told no one, only now you.'

ISBN: 9780143004592

ISBN-10: 014300459X

Published: 1st June 2006

Format: Paperback

Language: English

Number of Pages: 384

Audience: General Adult

Publisher: Penguin Australia Pty Ltd

Country of Publication: AU

Edition Number: 1

Dimensions (cm): 2.9 x 12.9 x 19.8

Weight (kg): 0.36

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.

You Can Find This Book In

This product is categorised by

- Non-FictionReligion & BeliefsJudaismJewish Life & Practice

- Non-FictionSociety & CultureSocial GroupsSocial & Cultural Aspects of Religious GroupsJewish Studies

- Non-FictionHistorySpecific Events & Topics in HistorySocial & Cultural History

- Non-FictionCooking, Food & DrinkRecipes & Cookbooks

- Non-FictionLiterature, Poetry & PlaysHistory & Criticism of Literature

- Non-FictionFamily & HealthRelationships & Families: Advice & Issues

- FictionModern & Contemporary Fiction