Faced with an escalating arms race, rising crime and terrorism, environmental deterioration, and long-term economic decline, people have retreated from commitments that presuppose a secure and orderly world. In his latest book, Christopher Lasch, the renowned historian and social critic, powerfully argues that self-concern, so characteristic of our time, has become a search for psychic survival.

Industry Reviews

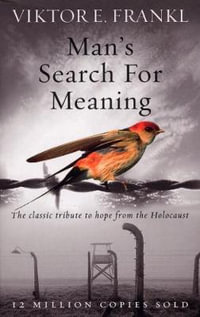

Lasch continues to enlarge upon ideas introduced in The Culture of Narcissism (1979), examining the more troubling manifestations of our "uneasy age" in the fluent style of his other writings. Primarily he laments the emergence of "survivalism," an orientation to life characterized by loss of faith in the future and, with it, a blurring of personal boundaries. (Survivalism is a less easily misunderstood term than narcissism.) A preoccupation with survival, its "grave and trivial" forms, persists because of the history of slaughter in our century and because of the continuing threat of nuclear war. In a notable chapter, "The Discourse on Mass Death: 'Lessons' of the Holocaust," he deplores the widespread vulgarization of that unique horror, and reminds us that Bettelheim and other survivors have stressed not the tactics of survival but the struggle to remain human under camp conditions. "The Minimalist Aesthetic" finds in modern art and literature evidence of an obscured, diminished sense of selfhood in a world without coherent patterns. When surveying the political landscape, Lasch uses psychoanalytic terminology (superego, ego) as he constructs and analyzes common debates about contemporary culture (stronger authority, moral enlightenment) and traces postwar reformulations of social theory. Writing from his own, strong philosophical foundation, he points out contradictions, even counterproductive ideas, in modern movements for feminism, environmentalism, and peace (whose goals he nevertheless shares). Throughout, Lasch answers some critics, clarifies ideas in his work that have frequently been misrepresented, and details his disagreements with assorted theorists (Clecak, Yankelovich, Bateson), strategically repeating themes familiar from earlier writings (the importance of play, therapeutic intrusions into everyday life). A vigorous, tightly unified work, characteristically aware of human needs and the strains in American society that subvert them. (Kirkus Reviews)