At a Glance

Paperback

624 Pages

624 Pages

Dimensions(cm)

4.9 x 12.8 x 19.8

4.9 x 12.8 x 19.8

Paperback

RRP $24.99

$23.75

or 4 interest-free payments of $5.94 with

In Stock and Aims to ship in 1-2 business days

In the 1930s, two opportunities existed for boys of Balmain, a working-class Sydney suburb: to be selected into Fort Street Boys School or to excel as a sportsman. At just sixteen years Danny Dunn has everything going for him: brains, looks, sporting aptitude - and luck with the ladies.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression few opportunities existed for working-class boys, but at just eighteen Danny Dunn has everything going for him: brain, looks, sporting ability - and an easy charm. His parents run The Hero, a neighbourhood pub, and Danny is a local hero.

Luck changes for Danny when he signs up to go to war. He returns home a physically broken man, to a life that will be changed for ever. Together with Helen, the woman who becomes his wife, he sets about rebuilding his life.

Set against a backdrop of Australian pubs and politics, The Story of Danny Dunn is an Australian family saga spanning three generations. It is a compelling tale of love, ambition and the destructive power of obsession.

About the Author

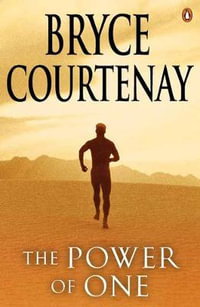

Bryce Courtenay is the bestselling author of The Power of One, Tandia, April Fool's Day, The Potato Factory, Tommo & Hawk, Solomon's Song, Jessica, A Recipe for Dreaming, The Family Frying Pan, The Night Country, Smoky Joe's Cafe, Four Fires, Matthew Flinders' Cat, Brother Fish, Whitethorn, Sylvia, The Persimmon Tree, Fishing for Stars, The Story of Danny Dunn, Fortune Cookie and Jack of Diamonds. Bryce Courtenay AM passed away in November 2012, aged seventy-nine, at his home in Canberra.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression few opportunities existed for working-class boys, but at just eighteen Danny Dunn has everything going for him: brain, looks, sporting ability - and an easy charm. His parents run The Hero, a neighbourhood pub, and Danny is a local hero.

Luck changes for Danny when he signs up to go to war. He returns home a physically broken man, to a life that will be changed for ever. Together with Helen, the woman who becomes his wife, he sets about rebuilding his life.

Set against a backdrop of Australian pubs and politics, The Story of Danny Dunn is an Australian family saga spanning three generations. It is a compelling tale of love, ambition and the destructive power of obsession.

About the Author

Bryce Courtenay is the bestselling author of The Power of One, Tandia, April Fool's Day, The Potato Factory, Tommo & Hawk, Solomon's Song, Jessica, A Recipe for Dreaming, The Family Frying Pan, The Night Country, Smoky Joe's Cafe, Four Fires, Matthew Flinders' Cat, Brother Fish, Whitethorn, Sylvia, The Persimmon Tree, Fishing for Stars, The Story of Danny Dunn, Fortune Cookie and Jack of Diamonds. Bryce Courtenay AM passed away in November 2012, aged seventy-nine, at his home in Canberra.

Industry Reviews

An epic from a superlative storyteller Harper's Bazaar This book is as much about Australia as it is about the characters Courtenay has created to illustrate the themes of love, family and fate Daily Telegraph

Chapter One

Danny Dunn returned to Balmain from the war understanding that he was no longer indestructible. When he'd joined up to fight at twenty, he'd been bulletproof. But coming home five years later, his childhood nickname – Dunny – seemed wholly appropriate. His life, almost since leaving the peninsula, had been shithouse, and it frightened him to think how he would cope as a civilian.

Back then, it hadn't taken long for some smart-arse kid in primary school to realise that by adding a 'y' to Danny's surname, in time-honoured Australian fashion, he could change it to the name for the toilet at the end of every backyard path. But a scattering of broken teeth, a few bloody noses and black eyes soon persuaded them that it was a cheap crack made at great personal risk to the joker.

By the age of fifteen, Danny was already a big bloke, a pound or two off fourteen stone. With feet as big as flippers, he swam like a fish and played in the Balmain first-grade water-polo team. On Saturday mornings he laced up his size-twelve football boots and played rugby union as a second-row forward for Fort Street Boys High, then in the afternoon he fronted in junior league for the mighty Balmain Tigers at Birchgrove Oval.

The old-timers at Balmain Leagues Club had been keeping an eye on him ever since he'd been in the nippers, and forecast big things for his football career. That he also played water polo as his summer sport was a matter of great concern to them. Everyone knew that water-polo players were a bunch of yobbos who played dirty and that severe or permanent injury in the pool was not unusual. In fact there was some truth in this. A game of water polo generally consisted of punches, kicks and scratches, resulting in bloody noses, bruises and torn ligaments that sometimes led to permanent injury. In an average game a player swam more than two miles and had three times as much hard body contact as a rugby-league player.

Furthermore, the Balmain polo boys and their followers richly deserved their dubious reputation for dirty tricks beneath the surface. As a venue, the Balmain Baths possessed an unenviable reputation. There was decking on only one side of the pool, which limited the referees' range, and the green murky water washing in from the harbour limited their vision, therefore a great deal of illegitimate underwater activity went undetected. Balmain polo players seldom lost a home game. They were renowned for their dirty tactics and considered to be the roughest players in the grade, a reputation in which their fans took considerable pride.

On several occasions Danny had been approached by a Tiger football coach who suggested that he take up a less dangerous summer sport than water polo; competition swimming was the one most often suggested. They pointed out that a truly special athlete comes along once in a generation and a Danny Dunn playing for a future Tiger's first-grade team was the kind of talent that could win premierships.

In football-mad Balmain it was advice a young bloke would be expected to follow, but Danny proved surprisingly stubborn and it was clear he had a mind of his own. He'd pointed out that he greatly enjoyed playing water polo, which kept him fit all summer for the winter football season, and that, unlike swimming, for which he had to be up early four mornings a week for two hours of intensive training, polo practice was in the evening and so met with his mother's approval. He could do his homework in the afternoon, practise in the evening, then get a good night's sleep and be ready for school in the morning. While he agreed he'd copped the odd bruise and bloody nose playing polo, even on one occasion a pair of black eyes, this was no different from playing football. Finally, he pointed out, if he were to maintain race fitness for swimming it would need to be his preferred sport summer and winter, and rugby league would of necessity become his second choice. This ended the discussion.

However, it had all come to a head when the Daily Telegraph did a feature in its sports pages on water polo and noted that it was one of the oldest team sports, along with rowing, in the Olympics and that water-polo was first played in Australia at Balmain. The article went on to say that, despite Australia's long history in the game and the genuine and enthusiastic support for it, we had never played at Olympic standard. The upcoming Berlin Games were an ideal opportunity for Australia to test its mettle in the water.

As further proof that we were ready for international competition, the newspaper cited as its authority György Nagy, the Hungarian Olympic coach at present visiting the country. Nagy had announced that he was greatly impressed with the standard of the local game and that, in his opinion, an Australian team could hold its own against any European team. He strongly recommended that Australia attempt to qualify for the Berlin Olympics.

The Daily Telegraph then picked a tentative Australian team from the various polo clubs, justifying their choice. For Danny Dunn, the singular selection from Balmain, they'd added a note of caution:

While his brilliance as a centre back is unquestioned, it is to be hoped that such a young player will not be injured or permanently incapacitated in the rough and tumble of international competition. Young Dunn will be sixteen when the games are being held, and therefore eligible, but his progress at any future Olympic trial should be carefully monitored.

All this was pure speculation on the part of the newspaper, and what followed was at best a storm in a teacup, but, in Balmain, a small, close-knit and mainly working-class community, any contention involving sport and one of their own had the potential to roar out of the teacup and develop into a gale-force storm. Like a quarrel between a father and son that starts as a conniption and erupts to involve the entire family, the future of Danny Dunn, included in the speculative water-polo team going nowhere, soon involved the entire peninsula.

There wasn't much joy during those dark post-depression years, so pride in the sporting achievements of Balmain's sons and daughters often sustained the entire community. Danny, barely sixteen when he would supposedly represent his country, was big news regardless of the sport involved. So the argument was infinitely more complex than simply football versus water polo. For a poor Balmain kid, top-level sporting prowess of any kind was a way out. It meant a future, ensured a job and, providing you didn't hit the grog or go off the rails in some other way, earned you respect for life. It also brought high regard and honour to your family. So while most folk were Tiger fans, regardless of their loyalty to the rugby-league team, they found themselves ambivalent, thus effectively removing themselves from the front line of battle.

This left only the diehard football fanatics opposing the water-polo fans, the latter seeing Danny's selection as the ultimate vindication of their sport. The numbers were roughly equal, which always makes for a good stoush, and that afternoon in the pubs it was on for one and all. Moreover, everyone involved had long since forgotten that the selected team was no more than the informed musings of a bored sports writer searching for a different topic to write about.

The football mob finally had all the ammunition they needed: the danger to Danny wasn't only their considered and long-held opinion but also that of the Daily Telegraph – the authority on racing at Randwick, the dogs at Harold Park and the trots at Wentworth Park, and therefore expert in all things. Danny Dunn's carefully nurtured rugby-league career was about to be placed in jeopardy by a bunch of thugs in swimming trunks.

The new thrust of the footballers' argument was that, if local games were clearly dangerous, any mug could see what it would be like when your country's honour was at stake. If Danny was to play against those dirty, filthy, no-holds-barred wog and dago teams it would almost certainly greatly endanger his career as a footballer. In their minds they had him returning from the games a permanent cripple in a wheelchair.

The vernacular, liberally punctuated with invective, flowed like wine at an Italian wedding.

'Mark my words, that kid belongs on the football field. He's a Tiger to his bootstraps. And one day he'll be a Kangaroo – nothing more certain – he'll play for Australia!'

The reply from the polo mob was just as insistent. 'Mate, he's a fucking porpoise! Six foot two and built like a brick shithouse. He's the best centre forward in the country and he's not even sixteen!'

'Yeah, and that's the flamin' problem, ain't it? Why do you think we're keeping him in mothballs, in the juniors away from the big blokes? The lad's still growin', that's why!'

'Growin'? Ferchrissake, he's fourteen stone! He is a big bloke! Mate, yiz don't play centre forward if you're not as strong as a bloody Mallee bull!'

'You water-polo bastards don't give a fuck, do yiz? Use him up, spit him out . . . plenty more where he come from! Well, there ain't, see! Danny Dunn's a fucking one-off, a sporting fucking genius! Youse could bugger him forever!'

'How's that?'

'Mate, in rugby league it's all out in the open. You biff someone. He biffs you back. A bit of claret, fair enough. The ref blows his pea and blame is duly apportioned, a warnin' or even an occasional penalty gets handed out. Open, fair, decent – handbags at five paces – all out in the open. Nobody gets hurt. Not like your mob. The ref can't see underwater, and soon as blink you'll knee a bloke in the balls or worse, tear his bloody arm off!'

'Bullshit! Danny can take good care of himself. Just you watch, mate, the kid takes no prisoners. Them wog players will jump into the pool baritones and come out fucking sopranos!'

By six o'clock closing on the night of the announcement of the hypothetical Olympic water-polo squad, several fights had broken out on the pavement outside various Balmain pubs, and a fair amount of claret was spilt. However, all blood was spilt in vain. The following morning, just after ten o'clock opening time, the argument was settled by Brenda, Danny's mother, in the front bar. 'I'm not taking sides. Danny's still at school and won't be playing in any Olympic team. That's all I've got to say!'

The water-polo supporters on the peninsula had gone from ecstasy to agony in twenty-four hours. At the soap and chemical factories, the ferry workshops, the foundry, coal loader, power station and wharves, there was little else discussed all day. In fact, the water-polo supporters grabbed anyone who was prepared to listen. 'The first water-polo game played in Australia was right bloody here! Here in the Balmain Baths! We was the first swimming club in Australia. Started in eighteen fucking eighty-three! Jesus! Yer don't go abusin' stuff like that! Lissen, mate, we was playing water polo before fucking rugby league was invented. We're the bastards with the tradition. Compared to us, them in league are still wet behind the bloody ears!'

By three-thirty knock-off time, it had been decided by the polo mob that a delegation would be led by Tommy O'Hearn, the union shop steward at the Olive, as the Palmolive soap factory was known to the locals. An ex-player and now assistant coach for first grade, he was ideally equipped to persuade Brenda Dunn to change her mind. The O'Hearn family had been polo boys for three generations; the game was in their blood.

Changing Brenda's mind was a task nobody took lightly; every attempt to persuade her to let an SP bookmaker to take bets in the pub had failed – her pub was the only one in Balmain that wouldn't allow gambling on the premises. 'Silly bitch . . . who does she think brings in the drinkers? They come in to have a beer and a bet; ya don't have one without t'other.' They didn't add that the SP bookmaker bought a lot of grog for his clients and also paid rent for the privilege of operating illegally on the premises. Nor did they reflect that the Hero never had any trouble with the police. And it wasn't because of bribery. Like every other publican, Brenda'd buy a cop a beer or two or serve him a free counter lunch, but that was it. The truth is there were no SP bookmakers, no stolen goods sold on pub premises and no other scams.

But Tommy O'Hearn was a smooth talker, a clever, persistent and patient bloke who had a fair idea what he was up against when it came to Danny's mum. He knew she was stubborn, and that approaching her directly would be pointless. The key was her husband, Half Dunn. 'Useless prick – all piss and wind. But maybe he has some influence, yer know, behind the scenes?' O'Hearn suggested.

Mick Dunn, six foot one inch and twenty stone, could drink twelve schooners of Reschs Draught and still appear reasonably sober as he sat propped on a reinforced bar stool at the main bar in the Hero from ten o'clock opening to six o'clock closing. He always wore exactly the same clobber, a white shirt and a humungous pair of grey tailor-made pants, the waistband of which reached almost to his armpits. From each knife-edged trouser leg protruded a pair of pointy-toed black and white, pattern-punched, patent-leather shoes, the instep and ankle of which were covered by carefully blancoed spats. Above them were grey silk socks held taut by suspenders. His open-neck shirt was collarless to accommodate the several chins that scalloped downwards to his chest, and he wore a solid-gold collar stud in the top left-hand buttonhole, to show that the omission of a starched detachable collar was deliberate, a matter of style. Finally, Half Dunn added a pair of crimson American barbershop braces with four square chrome clips. He was, he believed, a natty dresser, in the Runyonesque style he imagined Nicely-Nicely Johnson sported in Guys and Dolls, a book he tucked under his pillow each night before falling asleep.

It was often said of Half Dunn that he possessed an opinion on everything. There was no subject too obscure or trivial that he couldn't mature into a conversation. To give an example, on one occasion a punter came into the pub carrying a bag of corn on the cob he'd no doubt nicked from a produce boat he'd been unloading on the wharves. He ordered a seven, which indicated he was skint, and walked over for a chat with Half Dunn.

'What you got there, mate?' Half Dunn asked, pointing to the hessian bag.

'Yeah, mate, corn; fresh, straight off the boat. Let you have half a dozen for sixpence.'

'Nah, don't eat corn. No good fer ya,' Half Dunn replied.

'How's that, mate? Corn's good tucker,' the bloke said, taking the knockback in his stride.

'It don't digest,' Half Dunn volunteered.

'Digest? What d'yer mean by that?'

'You know, it gets into yer stomach, all them acids and stuff, fermentation, taking out the nourishment . . . it don't happen with corn.'

'Fermentation? Yer mean like grog . . . beer?'

'Yeah, gettin' the good out've the corn.'

The man looked quizzically at Half Dunn. 'How d'ya know all this shit?'

Half Dunn never missed a chance. He could pick up a double entendre in a flash.

'That's it precisely! Shit!'

'What's that suppose'ta mean?'

'You eat corn. Next mornin' you go for a shit. What do you see?'

'Eh?'

'Nothin's happened to the corn, mate. Them kernels are still in their little polished yellow jackets, same as when you swallowed them, digestion juices can't penetrate, see. No fermentation.'

The corn man took a sip from his seven and shook his head. 'Crikey! Ya learn somethin' every day, don't ya?'

'Stick around, son,' Half Dunn said, pleased with his erudition.

While Half Dunn could be described as a useless bastard, with no authority to do anything whatsoever except talk crap, like many seemingly unthinking people he possessed the capacity to talk to anyone on any subject, mining clues from their inanities and developing these to advance the conversation. Pubs by their very nature attract misfits and lonely men, and Half Dunn could talk to them all, adding to the pub's air of congeniality and increasing its appeal.

While Half Dunn drank more than his fair share of the profits and dispensed bonhomie and mindless opinions on everything from the perfidy of politicians to the training of ferrets, his wife, Brenda, put in a fifteen-hour day ending at 8 p.m. when she'd finally balanced the day's receipts, checked the cellars, cleaned the beer pipes and personally polished the bar surfaces. Tommy O'Hearn was right to treat her with respect. Nothing escaped her. Before the cleaners arrived, she always removed the Scott industrial toilet rolls, then replenished them after the cleaners had left, to prevent their being replaced by near empty ones brought from home in a cleaner's shopping bag. The Great Depression had left a residue of bad habits among basically honest people, and Brenda was onto every cleaning shortcut and sly trick in the trade.

Even the bartenders knew better than to pocket the cash from the odd middy. Brenda had been known to stand on a bar stool and punch the daylights out of a six-foot barman she'd caught short-changing a drunk patron. She ran a tight ship and a spotlessly clean pub. While she left the bragging to Half Dunn, she would occasionally claim, with justifiable pride, that her last beer at night tasted as fresh as her third one (the first two were always discarded), and no one ever disputed this.

But generally Brenda came as close as a woman may to being taciturn. She was different in almost every way to Half Dunn. Just five foot and half an inch, at seven stone she was as petite as Mick was grossly fat. Even though Michael Dunn's name appeared above the main entrance to the pub as the licensee, she was most definitely the boss. While she was as conscientious as any wife in the 'Yes, dear' department and never put her husband down in public, it was apparent to the regulars that his opinions counted for bugger-all. She opened the pub doors precisely at ten each morning and she'd show the last drunk the pavement at precisely five minutes past six each evening; in between opening and closing, the decisions she made ensured that the Hero was one of the most successful and best-run pubs on the peninsula.

Brenda Dunn fuelled all this effort with half-consumed cups of sweet black tea and Arnott's Sao biscuits, ten of which she'd place in her apron pocket of a morning. When the pub closed she would repair to the backyard where three magpies waited expectantly for the brittle Sao crumbs. She also smoked three packets of Turf Filters a day. More precisely, she'd light sixty fags, take an initial puff to get each one going, then carefully rest the cigarette on one of the heavy glass ashtrays advertising a brewer or whisky distiller, which she placed, she always imagined, at points she frequently passed. More often than not, as she reached for the cigarette to take a second drag, it would have collapsed into a fat grey ash worm. Some clever patron once worked out that if she got an average of one and a half drags from every fag and there were twenty potential puffs in each, she'd only smoked four and a half cigarettes a day.

What Tommy O'Hearn didn't know, was that Brenda's character had been forged out west in a poor farming family, where hard, thankless work began at dawn and ended after dark. There was never time for idle chatter, even about rain, that rare and precious, almost legendary occurrence. She'd lost her two elder brothers in the Great War, one at the Somme and the other, who'd come through the horrors of trench warfare relatively unscathed, in the Spanish Flu epidemic that raged through Europe in late 1918 and in the next two years spread around the world killing more than twenty million people. The eldest of the three remaining daughters, Brenda was sent at sixteen to work as an upstairs chambermaid in Mick's parents' pub, the Commercial Hotel in Wagga Wagga. Lonely and entirely ignorant about sex, within six months she was up the duff to eighteen-year-old Mick Dunn, their only son.

He would come into her tiny upstairs bedroom at the crack of dawn before anyone was up, gently shake her awake, then sit on the end of her narrow iron bed and invent outrageous and amusing stories about the town's notables, soon sending her into stifled giggles. An initial bold wake-up kiss on the forehead had developed over time into a cuddle on a freezing winter's morning when she'd let him creep under the bedcovers. Mick was already a huge lad, six foot one inch and starting to go to fat. The bed was very narrow, and the tiny housemaid failed to understand that the fumbling, kissing and rearranging of their bodies was bound to lead to penetration and, for Mick, almost instant ejaculation.

Soon after Brenda arrived, the regular barmaid fell ill and Brenda was called from her duties upstairs to clean the tables, wash glasses and keep the bar area clean while Dulcie, Mick's mother, took over the bar. By the end of the week Dulcie Dunn was so impressed with Brenda that she kept her downstairs and Fred raised her salary by two and sixpence a week. 'If Bob Barrett asks, you're to say you're eighteen,' she'd instructed Brenda. A rise in pay to pass on to her family was all the incentive their young housemaid needed to conceal her age from the local police sergeant. Besides, the downstairs main bar was far more interesting than making beds, sweeping and scrubbing floors, and cleaning out toilets and bathrooms. Never again would she have to scrub the upstairs passage on her hands and knees, enduring the leers and sly winks from commercial travellers bound for the bathroom with only towels that bulged with their early-morning erections wrapped around their waists.

Brenda proved to be a hard worker, quick to learn, good with the till, and demonstrating remarkable initiative for one so young. She was generally liked by the patrons, had a pleasant but firm way of persuading inebriated drinkers to go home, possessed very nice table manners, was modest, disarmingly shy and scrupulously honest, and was a Roman Catholic to boot. But soon the sharp-eyed gossips and stickybeaks in town started to whisper and point as the diminutive Brenda began to show. Dulcie and Fred were secretly delighted once they learned of the clandestine early-morning coupling. A generous donation to the church building fund allowed Father Crosby to waive the reading of the banns and the wedding proceeded as quickly as possible. Mick, their phlegmatic, indolent and generally useless son, had at least succeeded in sowing the seed for what they hoped would be their first grandson.

Fred and Dulcie Dunn had also married at eighteen and sixteen respectively, though, in their case, from choice rather than necessity. They'd been inseparable since their last year in primary school. Five years after their wedding, they'd taken over the Commercial Hotel from Fred's parents, and their son, Michael Donovon, was born in January 1900, the year before Federation, ten years after the marriage, when they'd just about given up hope of having a child.

Fred was a big man by most standards and as strong as an ox. Dulcie was long limbed and taller than most of her generation, so it was no surprise when she gave birth to a large child. Michael was the apple of his mother's eye and spoilt rotten from the very beginning. She would hear no ill spoken of him or his ballooning weight, until at eighteen, she had to face the truth. The army refused to recruit him to fight on account of his obesity. They'd never heard the term before and consulted Dr Light, the family physician, who told them the word basically meant grossly overweight. Dulcie was finally forced to agree with her husband that her precious son was a bone-idle slob and dangerously close to becoming an alcoholic. Fortunately, armistice was declared before the real reason for their son's rejection was revealed. Mick's only assets – dubious in a country boy and in particular a publican's son – were that he was mild mannered (in fact a coward) and could talk the hind leg off a donkey.

Mick and Brenda were married at the newly consecrated St Michael's Catholic Cathedral on a scorching January Saturday. Brenda's twin sisters, Bridgit and Erin, were the bridesmaids and Brenda's father, Patrick O'Shane, gave her away, despite the 104 degree heat, in the same heavy Irish tweed suit, good woollen shirt with starched detachable collar and side-buttoned boots he'd worn when he married her mother Rose in 1895 in the town of Galway on the shores of the River Corrib in County Galway.

However, all the hasty 'bun in the oven' wedding arrangements turned out to be unnecessary; at four months Brenda miscarried a baby girl. Young Dr Light, after performing a curettage, advised Brenda to try to delay a year before the next pregnancy. 'You're very small and all the Dunns are big men,' he warned. 'You'll need to be in excellent health.'

Danny Corrib Dunn, nine pounds four ounces at birth, was born on the 4th of July 1920. The long and painful labour was no surprise to Dr Light, nor was the damage to Brenda's plumbing; he warned her never to attempt to have another child.

Dulcie and Fred were delighted with Danny, apart from the initial shock when the nursing sister unwrapped the swaddling blanket and they observed their grandson's dark hair, tiny brown fists and olive complexion.

Although Mick's incompetence couldn't have had anything to do with the miscarriage, they had nevertheless been secretly worried and then vastly relieved when the second pregnancy turned out well. The marriage had proved fruitful in two ways: a grandson, but also a highly competent daughter-in-law.

By the time he was christened, the baby weighed eleven pounds two ounces and his abnormally large feet protruded from the end of his christening gown. It was impossible to ignore his jet-black hair and olive skin, surprising when both parents were so fair skinned and freckled. Brenda's hair was commonly referred to as titian and Mick's was the colour of a red house brick. At the christening party held at the pub afterwards, when the baby had been produced for inspection, Fred had heard one of the inebriated guests snigger, then ask in a loud whisper, 'Any Abos seen hanging around outside the pub this time last year?' The publican had grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and sent him out the back door nose first into the dirt.

Brenda, flat as a pancake in front, had no means of satisfying Danny's voracious appetite, so he was bottle-fed from an early age. Nor was she allowed much time to enjoy her baby. Fred and Dulcie realised that they now had a daughter-in-law who had the basic nous to run the pub, with a bit of training. Fred had always wanted to go on the land up north to breed racehorses, possibly the Hunter Valley, but somewhere close enough to Sydney, and Randwick Racecourse. Dr Light had diagnosed a dicky heart and advised him to remove himself from the daily stress of running a busy pub. Both parents had realised that Mick wasn't capable of taking over and it had seemed for a time that they would have to sell. But the arrival in their lives of the little Irish lass, now their daughter-in-law, changed everything, and they could begin to plan for a retirement in which Fred could fulfil his long-held ambitions.

Danny was handed over to a young nursemaid and Brenda's training as a publican began in earnest. Meanwhile Mick was earning the sobriquet Half Dunn, never quite able to complete a given task and spending more and more time on the customer side of the bar, where his elbow and his mouth were the only parts of his rapidly expanding person put to serious work.

Three years into the marriage, when Brenda had assumed almost the entire responsibility for running the pub, and Fred was on the eve of his early-retirement dream, Dulcie was diagnosed with breast cancer.

They had to move instead to Sydney so she could have a mastectomy and undergo the latest radiotherapy treatment. The pair bought a rather grand Federation house in Randwick with the twin advantages of being close to a major hospital and the famous racecourse, where Fred hoped over a few years to establish himself as both a racing identity and a breeder of quality bloodstock if all went well.

They returned to Wagga to say their goodbyes to family and friends and to finally leave the pub in Brenda's care, although not before the little vixen had handed them a lawyer's document requiring them to put the pub into their son's name. In Brenda's mind this was a necessary precaution. As a child she'd often enough heard the axiom from her mother, Rose, that gambling defeats the rewards of a woman's hard work, and that horses in particular send families to the poor house, especially the families of Irishmen. Fred's declared ambition to breed racehorses and his love of the turf concerned her greatly, and she didn't want a destitute father-in-law and his cancer-riddled wife descending on them and resuming ownership of the Commercial Hotel. One rotten Dunn was enough in Brenda's life. Mick's parents still demanded half the monthly income from the Commercial Hotel, even though they were wealthy by the standards of the time, and had been saving for Fred's dream stud farm all their lives.

Fred agreed to Brenda's demands, with the proviso that, if the pub were sold before both he and Dulcie died, they would be entitled to half the proceeds. With the change of ownership, there was now a pub in the Dunn name for the third generation, and Fred was justifiably proud.

More hard years followed the drought in the south-west, and while the Commercial Hotel continued to do well, dividing the profits was burdensome. Brenda was still supporting her family on the farm and paying for her twin sisters to attend the Presentation Convent boarding school at Mount Erin. Making ends meet was a constant struggle. Her one consolation was that young Danny was growing into a lively boy – quick, lean, long-limbed, active and intelligent.

No matter how rushed she was at the end of each day, Brenda made sure she read to him in bed every night. Danny, she'd decided, was going to go to university, even if it killed her. She was aware that this was a lofty ambition, well beyond her station in life, and that she could never divulge it to anyone without appearing presumptuous and uppity. She was still regarded by the town's respectable Protestant families and wealthier Catholics as bog Irish, and definitely from almost the bottom of the working class, despite her new status as a publican. At that time, women like her were not expected to achieve anything through their individual efforts, and to even entertain the possibility was considered immodest, unseemly and suspicious; such women simply married their own kind, bred, cooked, scrubbed, skimped and struggled until they died of overwork and lack of attention.

Brenda had been dux of her small country school when she finished in form three, the level at which most students, having reached the permitted school-leaving age, discontinued their education. Her parents had not attended the end-of-year prize-giving, where she'd received two books by Ethel Turner, Seven Little Australians and Miss Bobbie – the first tangible evidence that she was a bright and clever student.

Shortly afterwards, her parents had received a visit from the district school inspector, Mr Thomas, prompted by the young teacher, Linley Horrocks, on whom Brenda, along with every other girl in her class, had a secret crush.

Horrocks had not himself gone out to see Mr and Mrs O'Shane because he was a Protestant and a Baptist and felt that the much older and more senior Mr Thomas, a Catholic and known to be a prominent lay member of St Michael's, Father Crosby's parish in Wagga Wagga, would have much more influence with them.

By his later account to Horrocks, the interview with Brenda's parents had not gone well. As it transpired, they'd just received the news of their son's death at the Battle of the Somme.

Brenda had not been permitted to be present at the interview, which had taken place in the tiny front room of the farmhouse, referred to by her mother, with the little pride she had left in her, as 'the front parlour'. It was only used for the very occasional socially superior guest who visited the lonely homestead.

The curtains were drawn against the fierce sun and the window kept closed to protect the precious brocade curtains, brought from her mother's home in Kilcolgan, Ireland, so the room was at damn-near cooking temperature. Mr Thomas was clad in weskit and tie, having removed his jacket as a concession to the unrelenting heat, but was decidedly uncomfortable; the inside of his starched collar was soaked, the rim cutting into his neck. His white shirt under the woollen weskit stuck uncomfortably to his stomach as he addressed Brenda's parents.

'Mr and Mrs O'Shane, it is not customary for me to travel to a pupil's farm to talk to her parents,' he began somewhat pompously. 'However, in this particular instance I consider it a pleasure rather than a duty.' He paused for the expected effect, didn't get a reaction, put it down to nerves, then continued, 'I have, some might say, the onerous task of being the school inspector to all the schools in the south-west of this great state of ours. I say this only to emphasise that I am in a position to witness the progress of several thousand children, some tolerably competent, others, I regret to say, less so.' He uncrossed his legs and leaned forward for emphasis, his soft hands with their clean nails resting on his knees. 'But, every once in a while, a rose appears among the thorns. That is to say, an exceptional student.' He paused for further effect before continuing. 'I am happy to tell you that your daughter has a very good head on her shoulders. She is, I believe, one of the brightest we have in this part of the state.' Thomas leaned back, folded his hands over his stomach and beamed expectantly at the two still entirely motionless and expressionless adults.

The school inspector was sitting in one of the two overstuffed armchairs, upholstered in the same brocade as the curtains, while both parents, their backs pressed into straight-backed wooden dining chairs, continued to stare into their laps. It was as if they were yet again facing the bank manager.

Rose O'Shane had perhaps once been pretty, but now her face was work-worn and her pale-blue eyes no longer curious; her hair, pulled back into a hasty and untidy bun, was almost entirely grey, with just the faintest suggestion of her daughter's lovely titian colour. Patrick, her husband, was bald on top, with a few copper-coloured strands of hair mixed in among the grey. Surprisingly, considering the rest of his raw and sun-beaten face, his pate was smooth and unblemished. The rim of the battered bush hat he'd removed when he entered the parlour had created a clear line across his brow an inch or so below what must once have been his hairline. Above it the skin was undamaged; below it his face was pocked with skin cancers, its peeling, scaly surface bright puce.

The silence continued well after Thomas's deliberately prolonged smile had faded. He was not accustomed to being ignored and it was becoming clear that the O'Shanes were not receiving the good news in a manner he might have expected, nor showing him the respect he merited as a man of some standing in the south-west, a fellow papist and their obvious social superior.

'If your daughter is allowed to complete her high-school education in Wagga, who knows, after that she may well qualify for a scholarship to the university,' he ventured. Still getting no reaction he added quickly, with what was intended to be a disarming chuckle, 'When the time comes I dare say I can use what little influence I have with the Education Department in Sydney.' His tone clearly implied that a nod from him to the scholarship board was all it would take. 'We don't make a request very often, so when we do . . .' he left the sentence uncompleted, covering his arse just in case, not quite committing to the full promise.

Patrick O'Shane quite suddenly came to life, leaning forward, looking up from his hands sharply at Thomas. 'And for sure, who would it be paying for this fancy education now, Mr Thomas? I'll be tellin' you straight, it'll not be us.' As suddenly as if he'd spent his allotment of words, he fell silent, his eyes returned to his lap and his work-roughened hands, skinned knuckles and dirty fingernails; the thumbnail on his left hand was a solid purple, not yet turned entirely black, the result of what must have been a fairly recent and painful blow.

'Well . . . er . . . urrph,' Thomas said, clearing his throat, 'I'm sure we could come to some arrangement, some accommodation . . . with the school hostel, and the various textbooks she'll need . . . If you could possibly add . . .'

Patrick O'Shane looked up sharply, this time jabbing his forefinger at the school inspector, his expression now angry. 'Arrangement! Accommodation! Hostel! Books!' he repeated as if each word were intended as an expletive. 'And what would you be meaning by 'add'? We've done all the adding we can, Mr Thomas. We've added two sons fighting for this country in a war no self-respectin' Irishman could justify, fighting on behalf of that unholy Protestant whore, Mother England! One of them will never come home. We've added the sweat from our brows and the strength of our backs to work the unforgiving and endless dust plain. The saltbush and pasture are all but gone and the few starvin' ewes still left to us can't feed their lambs; the dams are empty and so are our pockets. There's nothing left for man nor beast and we haven't had any decent rain for three years. And you ask . . . you have the temerity to ask, 'If you could add'!' He slapped his right hand down hard onto his knee. 'Mary, Mother of God! Have we not done all the adding and has it not all come to nought, to bugger-all?'

Thomas, taken aback by the sudden tirade, could nevertheless see where Brenda's intelligence originated. He had the nous to know that offering his sympathy would only exacerbate the situation. 'Perhaps the convent?' he stuttered. 'I . . . er, could talk to Father Crosby . . . I'm sure —'

'That old fool and his building fund!' Patrick O'Shane exclaimed in disgust. 'You don't get my drift, do you now, Mr Thomas?' He paused momentarily. 'Never you mind the good head on her shoulders, our daughter also has two good hands and a strong back. She can scrub and clean and do domestic work for people of your kind in town. Her mother and I can no longer go it alone. We have two other daughters, twins, to feed as well. She's the eldest now. Don't blame us, sir. This godforsaken country stole my boys! Drowning them in mud, murderous shrapnel and sickness and robbing us of their strong hands and broad backs for years, one of them gone forever. She'll not be going back to school! You may be certain of that now, Mr School Inspector!'

Brenda accepted her father's decision calmly. After all, they were poor and she was a girl, with no reason to expect anything more than her mother had been granted in a thankless life of childbearing and hard work.

However, Danny's education had been her overriding ambition from the moment he was born, and she waited eagerly for the day when it could begin. A tall, sturdy, curious and confident little boy, Danny was more than ready for school at the age of five and a half. But in January 1926, disaster struck, at least in Brenda's terms of reference. Danny was due to start school in February, but a few days after Christmas he had asked if he could have ice-cream for dinner. As ice-cream was a special treat, Brenda asked him why. Danny had a voracious appetite and rarely refused to eat what was placed in front of him.

'Because my throat is very sore, Mummy,' he'd replied.

The following morning his face was deeply flushed, he had a temperature and could barely talk. She'd taken him off to see Dr Light who, after an examination, announced that Danny had diphtheria.

Brenda, not usually given to panic, burst into tears, whereupon Dr Light attempted to reassure her. 'Mrs Dunn, Danny's a strong, healthy little boy – there's no reason he shouldn't recover.'

But Brenda wasn't new to diphtheria. She'd seen it in her own childhood when all three children on a neighbouring farm had died from the disease. She knew it as a scourge that killed hundreds of children every year. She was also aware that, even if a child lived, there was a danger of a weakened heart or damage to the kidneys or nervous system, in some instances even incurable brain damage.

Danny spent the following week in hospital drifting in and out of delirium. Brenda stayed at his bedside and watched in despair as his fever worsened and the disease spread its toxins through his small body. She would sponge him for hours in an attempt to reduce the fever and try by sheer willpower to draw the disease out of him.

She'd left the running of the pub to Half Dunn with no instructions – a recipe for certain disaster but of no possible consequence now. She frequently sank to her knees beside the bed and prayed, saying her Hail Marys promptly every hour, then begging God, if necessary at the cost of her own life, to save her son. If she slept it was for no more than an hour or two and she'd wake exhausted and guilt-ridden.

Half Dunn visited every evening and brought her a change of clothes and two cold bacon-and-egg sandwiches, the only thing he knew how to cook. Brenda would thank him, 'I'll have them later, dear,' and put them aside. She would feed them to an ageing golden Labrador named Happy, who was permanently ensconced on the front verandah of the children's ward when she went outside early for the first of four cigarettes she smoked each day. The old mutt thought all his Christmases had come at once. Happy had accompanied his master, who'd been admitted three months previously and had subsequently died. Afterwards the dog had refused to leave. On two occasions someone had agreed to adopt him, but he'd made his way back to the hospital at the first opportunity. On one such occasion he'd been taken bush to an outlying homestead and came limping back to the hospital a week later with his paws bleeding and one of his ears badly tattered and almost torn off. How he'd survived the trip through the bush at his age was close to a miracle. His wounds were dressed and he was allowed to stay.

Over the second week Danny's fever lessened and he began the slow road to recovery. Throughout this period Brenda lived with the fear that her son might suffer permanent damage to his heart or brain. Despite Dr Light's assurance that he was coming along nicely and that there appeared to be no abnormal signs in his recovery, the die was cast, and for the remainder of his childhood she would fuss over his health. The slightest sniffle brought her running with the cod-liver oil; a cut or abrasion, and the iodine bottle appeared at the trot. But Danny recovered completely and seemed no worse for the experience. Despite his mother's over-enthusiastic ministrations he was to become a rough-and-tumble kid, eager to play any kind of game and quite happy to take the school playground knocks and bumps without complaint.

Incidentally, Happy decided he couldn't live without Half Dunn's bacon sandwiches, and agreed to be adopted by Brenda as the pub verandah dog. She'd hoped the old dog would be a mate for Danny, but, as they say, you can't teach an old dog new tricks and Happy only had eyes for her. Half Dunn would make Happy's favourite tucker every morning, but the dog would only accept the offering from his mistress. On one occasion she'd been away at her parents' farm for the weekend and had returned to find an unhappy Happy with his nose beside four uneaten bacon-and-egg sandwiches, which he proceeded to wolf down the moment she granted him permission to do so.

Brenda, grateful for her son's full recovery, had only one abiding regret: the diphtheria and Danny's lengthy recuperation meant he had missed a precious year of school. In fact, when he started school she discovered half the class was aged either six or seven, but she ever afterwards felt that she'd let a precious year of her son's education slip by.

In April that year, after a long battle with cancer, Dulcie died at the comparatively young age of fifty-three, followed three months later by Fred, after a sudden and massive heart attack on his way to the corner newsagent to get the morning paper. His friends, travelling up together on the train from Wagga Wagga for the second time in three months to attend the funeral, agreed that he'd almost certainly died of a broken heart over his beloved Dulcie.

The mourning contingent were well prepared for the journey up to Sydney for Fred's funeral with two crates of beer for the men and four bottles of sweet sherry for the ladies. After drinking their way through Cootamundra, Harden and Yass, they were pretty well oiled by the time the train rolled into Goulburn.

The conversation had progressed beyond the virtues of the dearly departed to discussion of his origins. His father, Enoch Dunn, was claimed to have won the pub in a game of poker on the Bathurst goldfields in the 1860s. The general consensus was that, all in all, the Dunn name had stood for something in the town and there was speculation about the present and the future.

Sergeant Bob Barrett, clad in a brown worsted suit that must once have buttoned over his front and looking decidedly uncomfortable out of his blue serge police uniform, seemed to express all their thoughts – well, those of the males present, anyway – when he ventured darkly, 'Ah, a truly blessed union, Fred and Dulcie, a tribute to the town.' He paused and raised his beer in memory. 'But, I'll give it to you straight. The boy has turned out to be a bloody no-hoper. If it weren't for that splendid young lass he married there'd be no pub and he'd be in the gutter, mark my words, a regular in my overnight lock-up. She keeps him out of harm's way, though gawd knows why, the useless bastard!'

But this tribute to Brenda didn't go unchallenged. The chemist's wife, Nancy Tittmoth, sailed in for her tuppence worth, her fourth glass of sweet sherry turning to pure acid as it touched her lips. 'Don't believe everything you see, Bob. Bog Irish, that one! Still eat with their fingers. The only way her kind can get out of the gutter is to land with their bum in the butter! That girlie has lots to answer for. Little hussy housemaid gets herself pregnant to the publican's son, both Roman Catholics, so they have to marry. Then her keeping the boy in a state of permanent intoxication so she can rule the roost. The hotel is in his name, of course, but as long as she hangs on to him, well . . .' she smiled primly, '. . . the little tart and her son with the girly hair can enjoy all the benefits of a fortunate marriage.'

Bob Barrett held his tongue. Everyone in town knew that Nancy had earmarked Mike Dunn for her eldest daughter, Enid, a sweet enough girl, though very tall, exceedingly plain and rather dull.

With the death of his parents, Mick and Brenda now had the total income from the pub and expectations of a further inheritance that might mean they could afford not only Mick's enduring thirst but Danny's education as well. To Mick's consternation and lasting bitterness, when the will was read, the Randwick property, Fred's half-share in two racehorses stabled at the racecourse and a not inconsiderable sum of money in the Bank of New South Wales had been left to Dulcie's two older sisters, both nuns approaching retirement.

It never occurred to Brenda that she could now afford to be a lady of leisure; she had always worked and she would continue to do so. But now she was no longer beholden to her parents-in-law, Brenda decided she'd had a gutful of running a country pub. Mick was all piss and wind and contributed little, either as a husband or a worker, besides his gift of the gab. She'd had her fill of commercial travellers stealing towels or jacking off in bed and leaving sperm stains on the sheets; she was sick of locals defaulting on their monthly beer tab, of drunks fighting or throwing up on the pavement outside. And Sergeant Bob Barrett, older than her father, the dirty old sod, propping up the bar most nights for an hour after closing when she was exhausted, ogling her as he downed a couple of complimentary schooners and a plate of ham sandwiches. She was sick of it all. The final straw came when one morning she'd gone out to feed Happy and found him dead. The ageing verandah dog hadn't shown any signs of being poorly. He'd simply passed away in his sleep. Brenda shed a quiet tear, sorry that she hadn't been present to say goodbye and to whisper into his tattered ear that she loved him. She decided she wanted a bigger world, and it was time her bright young son was educated in the city.

Brenda felt she'd fulfilled her duty to her own family. She'd put the twins through convent and paid for courses in shorthand and typing. While she still helped financially with the farm, good rains had fallen and the saltbush was coming back. She'd even noticed a gleam of hope occasionally in her mother's pale-blue eyes. Confident she would survive in the big smoke, they sold the pub to Toohey's Brewery in August 1929 and moved to Sydney, where they rented a small house in Paddington while Brenda looked for a suitable pub to buy. She thought she'd received a good price for the Commercial, but she was astonished at the pub prices in Sydney. After a few months she was beginning to wonder if she'd been wrong to sell up and leave Wagga. Then the New York Stock Exchange crashed, the effect resonating around the world to panic investors and set in train the Great Depression. Suddenly, cash was king and she found two run-down pubs, the Hero of Mafeking, in the working-class suburb of Balmain, and the King's Men, in Parramatta. While the Parramatta pub was a slightly better buy, she'd discovered that each year the brightest two kids in their final year at Balmain Primary School would be chosen to attend Fort Street Boys High, a selective school with an enviable academic reputation. For a working-class boy it was the first step to a university education and Brenda fancied her chances with Danny, who was proving to be very bright. It was for this reason that she ignored the advice of the hotel broker and chose the more run-down of the two pubs.

The gathering hard times had bankrupted the licensee, but Brenda reasoned that men still needed a drink, no matter how hard things became. She soon discovered that the pub had been cheap for several very good reasons. The previous publican had a reputation as a surly bastard who drove away more patrons than he ever attracted. With thirty pubs to choose from on the peninsula, this was not a very intelligent way to conduct business. Furthermore, the Resch's brewery rep had cut off his supply when he couldn't come up with the cash for his deliveries. The place was so run-down, shabby and dirty that the brewery had decided not to follow their usual practice of buying the freehold and installing a lessee, thus tying the pub to their beer forever. The premises were infested with cockroaches and rats, although the former were a product of Sydney's humid summers and the latter – not exclusive to the pub – emanated from the wharves and ships anchored at the docks. In fact rats on the peninsula were in plague proportions, adding to the general sense of misery since the Wall Street crash. Everything and everyone went hungry, from the packs of emaciated dogs that roamed the streets, to the families who had once owned and loved them. Only the cats had full bellies.

Danny, now nine, was enrolled in the local primary school in time for the first term of 1930. Brenda wasn't happy that he was growing up in a pub, but she'd managed to keep him out of the pub in Wagga and she'd do so again in Balmain.

The Balmain peninsula jutting out into Port Jackson was distinguished by the beauty of the harbour and the polluting industry that festered at the water's edge. It was an inner-harbour suburb of Sydney, with Iron Cove on the west, White Bay to the south-east, Mort Bay on the northeast and Rozelle to the south-west. But Balmain did not regard itself as a part of anything or anyone. To the people who lived in its just over half a square mile, it was a different place, a separate village, a different state of being and of mind.

How this overweening civic pride had come about nobody quite knew. Clearly Balmain was superior to Rozelle, which was lumbered with Callan Park, a lunatic asylum. 'Yer gunna be thrown in the loony bin if yer don't behave!' was the customary threat to children growing up on the peninsula. Balmain boasted an impressive Italianate town hall of brick and stucco, and several handsome winding streets leading down to the two wharves or terminating in broad stone steps that led to jetties projecting into the sparkling harbour. Along Darling Street, rickety, swaying, clattering trams bore passengers down the steep slope to the Darling Street Wharf where they could take the ten-minute ferry ride to the city terminus.

Yet, despite its beautiful setting and impressive civic centre, Balmain exhibited all the signs of working-class poverty. Spidering out along the peninsula on either side of Darling Street were humble back streets of run-down wooden and sandstone terraces of one and two storeys fronting directly onto cracked and weed-infested pavements. The tiny backyards contained only an outdoor toilet and a washing line, a rope or wire strung from the top of the kitchen door to the dunny roof. The Daily Worker once described these workers' hovels as not fit for dogs to live in.

A coal loader left a residue of fine coal dust on Monday's washing, blackened the rind of dried mucus round the nostrils of the snotty-nosed kids, and added a sharp, acrid smell to the atmosphere. The air was filled with coal smoke from a power station and sulphur from a chemical factory near the Rozelle end, causing throats to burn and eyes to water. Two soap factories contributed the fetid stink of sheep tallow, and a host of small engineering factories added to the din and stink, squatting in niches and coves around the harbour.

Others may have described Balmain as poverty-stricken during the Great Depression and the ongoing misery of the thirties, but locals were largely unaware of their particular misfortune. While many of its working-class residents struggled more than most to survive – unemployment in Balmain was double the state average – they nevertheless possessed a peculiar and unreasoning pride: they came from Balmain and were therefore fiercely, even foolishly, tough and independent. 'Balmain boys don't cry' epitomised the breed.

They needed every bit of determination as the 1930s progressed. Moonlight flits were common – a huddle of cold and hungry urchins together with their desperate parents escaping down a dark street at midnight carrying between them everything they owned, unable to pay the rent or persuade the landlord to extend them any more credit. In winter people were reduced to rowing out at night to ships waiting to unload, dodging the water police, then stealing aboard like rats to pinch coal or vegetables from the holds. War veterans sold matches or busked outside pubs on harmonicas, playing the popular songs of the Great War and the roaring twenties. Men turned up at dawn to get a place in the labour queue, their stomachs rumbling or cramping with hunger after a dingo's breakfast – a piss and a good look around.

Balmain became a place of hungry, bronchial, barefoot children, many suffering from scabies. Paradoxically, the children attending school were well scrubbed, unlike those from other poverty-stricken neighbourhoods. Similarly Balmain men standing in the labour queues were, as a general rule, neatly shaved. This came about, not from fastidiousness, but because soap and shaving cream were stolen from the production line of the local Colgate Palmolive and Lever Brothers soap factories and handed out to friends and neighbours. There was always soap beside the tub, even if there was no food in the cupboard.

But Brenda had been correct. Although poverty gripped the peninsula and per capita beer sales had dropped, pub patronage increased. Tired and defeated men could go to the pub and know that they were not alone; it was neutral territory, where they could share a middy or a seven, have a whinge and a joke and talk football or the race results at Wentworth Park and Harold Park or at Randwick. They could linger over a beer beside another bloke and forget the labour queue they would both be joining the following morning, competing for a dwindling supply of jobs.

The Hero of Mafeking needed a lot of work if it was to become a decent pub, and although it had been cheap, repairs and renovations soon depleted the money in the bank, except for a small emergency reserve. In fact they went close to bankruptcy on several occasions. However, the resourceful Brenda, by skimping and saving, short-staffing, and working until she dropped as barmaid, cleaner, cellar-woman and publican, kept them afloat. She'd often enough wake with a start in the small hours of the morning, having collapsed from sheer exhaustion in the beer cellar, slumped against an eighteen-gallon kilderkin of beer. But somehow she contrived to build the pub's popularity as well as enable her parents to save their farm.

By the time the Depression had started to wane slightly towards the end of 1934, the Hero of Mafeking was considered one of the best of the thirty pubs on the peninsula. Brenda had introduced several innovations. In the main bar she got rid of the sawdust on the floor and, to the amusement of the competition, laid bright red and white checked linoleum and a couple of dozen three-legged bar stools along the length of the polished teak bar.

'Stupid bitch. Wait until some drunk slips on his own vomit or beer slops and breaks his fucking neck.'

She strategically placed three brightly painted firemen's pails each filled with an inch or two of sawdust so that anyone feeling the urge to throw up could reach them quickly.

Brenda made sure there were always fresh flowers in the parlour – the ladies bar – and laid a pretty rose-patterned carpet; she placed a couple of nice still-life prints on the wall together with a large glossy picture in an ornate gold stucco frame of the two royal princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret.

The first counter lunches were offered at the Hero of Mafeking: threepence for a middy of beer, two thick slices of bread (twelve slices to the loaf), cheese, boiled mutton or German sausage. Other pubs followed suit, but their mostly male publicans did little else to raise the spirits of their patrons.

Photographs of the great Balmain rugby-league players as well as other sportsmen of the past appeared on the walls of the main bar decently framed behind glass and not screwed permanently to the wall.

'Mark my words, they won't last ten minutes. Bludgers will soon have those under their jumpers and into the pawnbroker!'

But, with some rare exceptions, the patrons did no such thing. They responded well to being treated decently. Having a beer at the Hero became a pleasant experience, and to be banned for bad behaviour was considered a genuine disgrace.

Far and away Brenda's greatest innovation was her ladies' soiree. She invited the neighbourhood housewives to congregate in the shade of the pub's back verandah each weekday afternoon to enjoy one another's company while darning, mending, shelling peas or peeling potatoes for the family's evening meal. The single schooner of shandy that lasted each of them through the afternoon was free twice a week and half the usual fourpence on the other three weekdays.

'Silly drongo! Soon go broke handing out them free drinks to the sheilas!'

At this very popular afternoon gathering, involving at any time two or three dozen women, Brenda would be rewarded for her generosity with all the gossip, hard news and rumour from around the peninsula. No one in Balmain could scratch his bum without her knowing, and anything the opposition tried she'd know about, often before it happened.

To his credit Half Dunn had never objected to the financial help she gave her family, even when they'd been pretty skint themselves. Brenda never forgot that, accepting him for the lazy, bullshitting, useless lump of pomaded and nattily dressed lard he in fact was. In the end drinkers regarded him as a fixture, someone never short of a word, a cheeky remark, a clever quip or the latest joke.

By 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics, the Hero was solidly in the black and Brenda's reputation as a publican was at an all-time high. But the day she declared that, come what may, Danny wasn't going to the Olympic trials, many of the chairs on the back verandah of the pub remained empty, despite it being a free shandy day. Brenda was shocked. She had come to regard the women as friends and confidantes, but the empty seats symbolised a general disapproval. The women were appalled by her decision; they could never have afforded and would never have dared to make it themselves, and some thought she was giving herself airs.

Opportunities for working-class boys in Balmain were few and far between: they could excel as sportsmen or be selected to go to Fort Street Boys High School. It ultimately meant the opportunity for a decent job in the city, a clean job where you wore a white shirt, collar and tie, shone your shoes every morning and came home with clean finger nails, or with an honourable ink stain on your second and third fingers where you held your Croxley fountain pen. On a rare occasion it meant a scholarship to Sydney University. Even by proxy, Fort Street and sport made a big difference to how folk felt about themselves.

The alternative for a young bloke who wasn't super bright or couldn't kick a football, swim like a flaming porpoise, race a bike at the velodrome or go ten rounds in the ring at Rushcutters Bay Stadium was to follow his old man into the Colgate-Palmolive or Lever Brothers soap factories, the iron foundry, the ferry repair workshops or as a trainee crane driver at Walsh Bay. That is, if he was lucky enough to get an apprenticeship and didn't end up as a common labourer shovelling shit and guts at....

Danny Dunn returned to Balmain from the war understanding that he was no longer indestructible. When he'd joined up to fight at twenty, he'd been bulletproof. But coming home five years later, his childhood nickname – Dunny – seemed wholly appropriate. His life, almost since leaving the peninsula, had been shithouse, and it frightened him to think how he would cope as a civilian.

Back then, it hadn't taken long for some smart-arse kid in primary school to realise that by adding a 'y' to Danny's surname, in time-honoured Australian fashion, he could change it to the name for the toilet at the end of every backyard path. But a scattering of broken teeth, a few bloody noses and black eyes soon persuaded them that it was a cheap crack made at great personal risk to the joker.

By the age of fifteen, Danny was already a big bloke, a pound or two off fourteen stone. With feet as big as flippers, he swam like a fish and played in the Balmain first-grade water-polo team. On Saturday mornings he laced up his size-twelve football boots and played rugby union as a second-row forward for Fort Street Boys High, then in the afternoon he fronted in junior league for the mighty Balmain Tigers at Birchgrove Oval.

The old-timers at Balmain Leagues Club had been keeping an eye on him ever since he'd been in the nippers, and forecast big things for his football career. That he also played water polo as his summer sport was a matter of great concern to them. Everyone knew that water-polo players were a bunch of yobbos who played dirty and that severe or permanent injury in the pool was not unusual. In fact there was some truth in this. A game of water polo generally consisted of punches, kicks and scratches, resulting in bloody noses, bruises and torn ligaments that sometimes led to permanent injury. In an average game a player swam more than two miles and had three times as much hard body contact as a rugby-league player.

Furthermore, the Balmain polo boys and their followers richly deserved their dubious reputation for dirty tricks beneath the surface. As a venue, the Balmain Baths possessed an unenviable reputation. There was decking on only one side of the pool, which limited the referees' range, and the green murky water washing in from the harbour limited their vision, therefore a great deal of illegitimate underwater activity went undetected. Balmain polo players seldom lost a home game. They were renowned for their dirty tactics and considered to be the roughest players in the grade, a reputation in which their fans took considerable pride.

On several occasions Danny had been approached by a Tiger football coach who suggested that he take up a less dangerous summer sport than water polo; competition swimming was the one most often suggested. They pointed out that a truly special athlete comes along once in a generation and a Danny Dunn playing for a future Tiger's first-grade team was the kind of talent that could win premierships.

In football-mad Balmain it was advice a young bloke would be expected to follow, but Danny proved surprisingly stubborn and it was clear he had a mind of his own. He'd pointed out that he greatly enjoyed playing water polo, which kept him fit all summer for the winter football season, and that, unlike swimming, for which he had to be up early four mornings a week for two hours of intensive training, polo practice was in the evening and so met with his mother's approval. He could do his homework in the afternoon, practise in the evening, then get a good night's sleep and be ready for school in the morning. While he agreed he'd copped the odd bruise and bloody nose playing polo, even on one occasion a pair of black eyes, this was no different from playing football. Finally, he pointed out, if he were to maintain race fitness for swimming it would need to be his preferred sport summer and winter, and rugby league would of necessity become his second choice. This ended the discussion.

However, it had all come to a head when the Daily Telegraph did a feature in its sports pages on water polo and noted that it was one of the oldest team sports, along with rowing, in the Olympics and that water-polo was first played in Australia at Balmain. The article went on to say that, despite Australia's long history in the game and the genuine and enthusiastic support for it, we had never played at Olympic standard. The upcoming Berlin Games were an ideal opportunity for Australia to test its mettle in the water.

As further proof that we were ready for international competition, the newspaper cited as its authority György Nagy, the Hungarian Olympic coach at present visiting the country. Nagy had announced that he was greatly impressed with the standard of the local game and that, in his opinion, an Australian team could hold its own against any European team. He strongly recommended that Australia attempt to qualify for the Berlin Olympics.

The Daily Telegraph then picked a tentative Australian team from the various polo clubs, justifying their choice. For Danny Dunn, the singular selection from Balmain, they'd added a note of caution:

While his brilliance as a centre back is unquestioned, it is to be hoped that such a young player will not be injured or permanently incapacitated in the rough and tumble of international competition. Young Dunn will be sixteen when the games are being held, and therefore eligible, but his progress at any future Olympic trial should be carefully monitored.

All this was pure speculation on the part of the newspaper, and what followed was at best a storm in a teacup, but, in Balmain, a small, close-knit and mainly working-class community, any contention involving sport and one of their own had the potential to roar out of the teacup and develop into a gale-force storm. Like a quarrel between a father and son that starts as a conniption and erupts to involve the entire family, the future of Danny Dunn, included in the speculative water-polo team going nowhere, soon involved the entire peninsula.

There wasn't much joy during those dark post-depression years, so pride in the sporting achievements of Balmain's sons and daughters often sustained the entire community. Danny, barely sixteen when he would supposedly represent his country, was big news regardless of the sport involved. So the argument was infinitely more complex than simply football versus water polo. For a poor Balmain kid, top-level sporting prowess of any kind was a way out. It meant a future, ensured a job and, providing you didn't hit the grog or go off the rails in some other way, earned you respect for life. It also brought high regard and honour to your family. So while most folk were Tiger fans, regardless of their loyalty to the rugby-league team, they found themselves ambivalent, thus effectively removing themselves from the front line of battle.

This left only the diehard football fanatics opposing the water-polo fans, the latter seeing Danny's selection as the ultimate vindication of their sport. The numbers were roughly equal, which always makes for a good stoush, and that afternoon in the pubs it was on for one and all. Moreover, everyone involved had long since forgotten that the selected team was no more than the informed musings of a bored sports writer searching for a different topic to write about.

The football mob finally had all the ammunition they needed: the danger to Danny wasn't only their considered and long-held opinion but also that of the Daily Telegraph – the authority on racing at Randwick, the dogs at Harold Park and the trots at Wentworth Park, and therefore expert in all things. Danny Dunn's carefully nurtured rugby-league career was about to be placed in jeopardy by a bunch of thugs in swimming trunks.

The new thrust of the footballers' argument was that, if local games were clearly dangerous, any mug could see what it would be like when your country's honour was at stake. If Danny was to play against those dirty, filthy, no-holds-barred wog and dago teams it would almost certainly greatly endanger his career as a footballer. In their minds they had him returning from the games a permanent cripple in a wheelchair.

The vernacular, liberally punctuated with invective, flowed like wine at an Italian wedding.

'Mark my words, that kid belongs on the football field. He's a Tiger to his bootstraps. And one day he'll be a Kangaroo – nothing more certain – he'll play for Australia!'

The reply from the polo mob was just as insistent. 'Mate, he's a fucking porpoise! Six foot two and built like a brick shithouse. He's the best centre forward in the country and he's not even sixteen!'

'Yeah, and that's the flamin' problem, ain't it? Why do you think we're keeping him in mothballs, in the juniors away from the big blokes? The lad's still growin', that's why!'

'Growin'? Ferchrissake, he's fourteen stone! He is a big bloke! Mate, yiz don't play centre forward if you're not as strong as a bloody Mallee bull!'

'You water-polo bastards don't give a fuck, do yiz? Use him up, spit him out . . . plenty more where he come from! Well, there ain't, see! Danny Dunn's a fucking one-off, a sporting fucking genius! Youse could bugger him forever!'

'How's that?'

'Mate, in rugby league it's all out in the open. You biff someone. He biffs you back. A bit of claret, fair enough. The ref blows his pea and blame is duly apportioned, a warnin' or even an occasional penalty gets handed out. Open, fair, decent – handbags at five paces – all out in the open. Nobody gets hurt. Not like your mob. The ref can't see underwater, and soon as blink you'll knee a bloke in the balls or worse, tear his bloody arm off!'

'Bullshit! Danny can take good care of himself. Just you watch, mate, the kid takes no prisoners. Them wog players will jump into the pool baritones and come out fucking sopranos!'

By six o'clock closing on the night of the announcement of the hypothetical Olympic water-polo squad, several fights had broken out on the pavement outside various Balmain pubs, and a fair amount of claret was spilt. However, all blood was spilt in vain. The following morning, just after ten o'clock opening time, the argument was settled by Brenda, Danny's mother, in the front bar. 'I'm not taking sides. Danny's still at school and won't be playing in any Olympic team. That's all I've got to say!'

The water-polo supporters on the peninsula had gone from ecstasy to agony in twenty-four hours. At the soap and chemical factories, the ferry workshops, the foundry, coal loader, power station and wharves, there was little else discussed all day. In fact, the water-polo supporters grabbed anyone who was prepared to listen. 'The first water-polo game played in Australia was right bloody here! Here in the Balmain Baths! We was the first swimming club in Australia. Started in eighteen fucking eighty-three! Jesus! Yer don't go abusin' stuff like that! Lissen, mate, we was playing water polo before fucking rugby league was invented. We're the bastards with the tradition. Compared to us, them in league are still wet behind the bloody ears!'

By three-thirty knock-off time, it had been decided by the polo mob that a delegation would be led by Tommy O'Hearn, the union shop steward at the Olive, as the Palmolive soap factory was known to the locals. An ex-player and now assistant coach for first grade, he was ideally equipped to persuade Brenda Dunn to change her mind. The O'Hearn family had been polo boys for three generations; the game was in their blood.

Changing Brenda's mind was a task nobody took lightly; every attempt to persuade her to let an SP bookmaker to take bets in the pub had failed – her pub was the only one in Balmain that wouldn't allow gambling on the premises. 'Silly bitch . . . who does she think brings in the drinkers? They come in to have a beer and a bet; ya don't have one without t'other.' They didn't add that the SP bookmaker bought a lot of grog for his clients and also paid rent for the privilege of operating illegally on the premises. Nor did they reflect that the Hero never had any trouble with the police. And it wasn't because of bribery. Like every other publican, Brenda'd buy a cop a beer or two or serve him a free counter lunch, but that was it. The truth is there were no SP bookmakers, no stolen goods sold on pub premises and no other scams.

But Tommy O'Hearn was a smooth talker, a clever, persistent and patient bloke who had a fair idea what he was up against when it came to Danny's mum. He knew she was stubborn, and that approaching her directly would be pointless. The key was her husband, Half Dunn. 'Useless prick – all piss and wind. But maybe he has some influence, yer know, behind the scenes?' O'Hearn suggested.