At a Glance

298 Pages

21.59 x 13.97 x 1.7

Paperback

$37.43

or 4 interest-free payments of $9.36 with

orAims to ship in 7 to 10 business days

When will this arrive by?

Enter delivery postcode to estimate

Award-winning nature writer Jack Turner directs his attention to one of America’s greatest natural treasures: the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. In a series of essays, Turner explores this wonderland, venturing on twelve separate trips in all seasons using various modes of travel. He treks down the Teton Range, picks up the Oregon Trail in the Red Desert, and floats the South Fork of the Snake River. Along the way he encounters a variety of wildlife: moose, elk, trout, and wolves. From the treacherous mountains in the dead of winter to lush river valleys in the height of fishing season, his words and steps trace one of the most American of experiences—exploring the West.

Turner—who has lived in Grand Teton for three decades—designates the Greater Yellowstone as ground zero for the country’s conflict between preservation and development, and his accounts of the area’s conflicts with alien species, logging, real estate, oil, and gas development are alarming.

A mixture of adventure, nostalgia, and Americana, Turner’s rare experiences and evocative writing transform the sights and sounds of Greater Yellowstone into an intimate narrative of travel through America’s most beloved lands.

Industry Reviews

"There have been legendary Indians, mountain men, and mystics, but the West has never been loved by a greater poet-warrior than Jack Turner. In Travels in the Greater Yellowstone, he reveals treasures and threats to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem while taking us on the most intimate and informative tour of America's wildest lands." --John Passacantando, executive director of Greenpeace USA

"The essays are controversial, but part observation, part history, part rant, they all are worth reading." --The Denver Post

"Turner climbs the highest peaks and ventures out into the loneliest, most bear-haunted valleys to get a good look at Yellowstone before it well, not exactly disappears, but becomes something other than what it is. . . . Champions of Yellowstone and the truly wild West already know Turner's work. This one merits a wide audience, particularly in the Department of the Interior." --Kirkus Reviews

Introduction The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem 1

1 The View from Blacktail Butte 11

2 Opening Day on the Firehole River 29

3 Modern Wolves 52

4 Alpine Tundra: The First Domino 74

5 The South Fork 97

6 The Wyoming Range 117

7 The Deep Winds 140

8 Green River Lakes 163

9 Chasing Cutts 182

10 Grizzly Bear Heaven 204

11 Red Rock Lakes 227

12 Christmas at Old Faithful 244

Bibliography 265

Read an Excerpt

Introduction

It is a place of superlatives and fame. Home of the first national park and the world’s largest concentration of geysers and hot springs; the largest relatively intact temperate ecosystem in the United States; the youngest range in the Rocky Mountains, the oldest exposed rock in North America, the highest peak in Montana, the highest peak in Wyoming, and the largest glaciated region in the contiguous states; the source of the three largest rivers in the West; the largest elk herd, the largest bison herd, the largest number of grizzlies and wolves, the largest winter concentration of big game animals; the best big game hunting and fishing; a United Nations Biosphere Preserve and World Heritage Site; a place traversed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the Oregon Trail; home of the mountain men; the place where Owen Wister wrote the first Western—The Virginian; home to some of the fastest growing counties in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, to the wealthiest county in America, and to the most intense energy development in the nation. The list goes on and on. Some items are merely curious, some surprising, some are legendary and laden with emotion. It is a list that suggests both the extraordinary and the contradictory nature of a mass of land that in the last few decades has come to be known as Greater Yellowstone.

Greater Yellowstone encompasses about 18 million acres—the size of West Virginia—comprising parts of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Of that, Yellowstone National Park is 2.2 million acres, or roughly 12 percent. My subject is the larger entity, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

I first came into this country forty-seven years ago. Atfirst I came and went as a tourist. Forty years ago I began to work here as a mountain climbing guide. Thirty years ago I began to live here full-time. It is, in the deepest sense of the word, my home. I really don’t like being any place else. I’ve climbed, hiked, skied, canoed, kayaked, fished, hunted, and explored it in all seasons, always with pleasure. Like anyone who lives here and has a baseline of memories extending over nearly half a century, I’ve watched it change in ways that casual visitors would not notice, change in ways that will profoundly affect its future. The ice climbs I did as a young man are gone, and many of my favorite fishing holes have been closed by no trespassing signs; the mountains and rivers are often unpleasantly crowded, lands that were once open space are now glutted with houses. Bugs have arrived from Egypt, pollution from China. Even the seasons have changed: summer is longer, winter is warmer, and spring is earlier.

With recognition of those changes came a desire to understand the place where I live, what made it what it is, what made it different and unique, and what made it the object of such intense love. What is this place? What is its essence, its identity? The more I’ve understood the answers to these questions, the more dismayed I’ve become—and angry.

Greater Yellowstone is defined by similarities, affinities, and shared histories across many biological, geological, and geographical categories. We call it an ecosystem because the parts—whether a mountain, a river, a rock, a moose, or a fish—are not just a totality of things, but a functioning whole held together by an extensive series of mutual dependencies and interactions. It includes two national parks, part or all of seven national forests, three national wildlife refuges, lands under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management, an Indian reservation, state land, and private lands held by individuals and corporations. No single institution is devoted to its interests; no single person or group has authority over its destiny. Its heart is Yellowstone National Park, but in much the same way as a heart is dysfunctional without a body, the Park will become dysfunctional without the protection of a much vaster area surrounding it.

The original boundaries of Yellowstone National Park were arbitrary and had no relation to biological or ecological processes. Hiram Chittenden, one of the park’s early superintendents and author of its first notable guidebook, is clear on this point: “At the time when the bill creating Yellowstone Park was before Congress there had been no detailed survey of that region, and the boundaries, as specified in the bill, were to some extent random guesses.” Early visitors and park staff soon realized that the park was too small to safeguard its wildlife, most obviously because it failed to protect essential migration routes and winter grazing grounds outside the park that were used by elk, deer, antelope, and bison.

In 1880, only eight years after the park’s creation, Superintendent Philetus W. Norris recommended that the park’s boundaries be extended. In 1917, a writer named Emerson Hough first used the term “Greater Yellowstone.” Since then a combination of philosophy, science, history, and empirical data has made it apparent that adjoining lands required some form of protection in order to fulfill the park’s mission. For the past ninety years a variety of individuals and groups have struggled to resolve this issue. I have watched these struggles; in a few cases I played an active part in them. Some of my friends have devoted their lives to its resolution.

The sea change began with conservationist Aldo Leopold’s insistence that the land be treated as a whole, an idea he first set down in a 1944 rough draft entitled “Conservation: In Whole or in Part?” There are two kinds of conservationist, and two systems of thought on the subject.One kind feels a primary interest in some one aspect of land (such as soil, forestry, game, or fish) with an incidental interest in the land as a whole.The other feels a primary interest in the land as a whole, with incidental interest in its component resources.The two approaches lead to quite different conclusions as to what constitutes conservative land-use, and how such use is to be achieved.The first approach is overwhelmingly prevalent. The second approach has not, to my knowledge, been clearly described. Now the land as a whole—an ecosystem—has been described, but most conservation efforts still focus on the parts. We fret, argue, and create management plans for many species, one for an endangered species of trout, another for the nearly extinct lynx population, another for a creek destroyed by cattle grazing. These efforts to conserve Greater Yellowstone have encountered formidable obstacles: conflicts with traditional uses of the land, such as ranching, resource extraction, and real estate development. Most visitors to the Yellowstone country do not realize how serious the conflict has become. And there is a deeper problem. Management plans treat the ecosystem as a machine whose parts are maintained as we wish (elk populations) or removed and replaced at will (wolves), instead of a whole whose parts are created and maintained by one another without our assistance—a wild ecosystem.

To gain public acceptance of the ecosystems conservationists created new maps that represented biological reality instead of political reality, maps that required thinking at new spatial scales about the complex interactions among flora, fauna, and the nonbiological world of rock, water, fire, and climate. The first maps of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem made the idea of Greater Yellowstone real to the American public. I remember seeing those first maps and feeling we had made a quantum leap in understanding the natural world. But it was only the first step and, ironically, conservation organizations are now less and less inclined to publish such maps.

With the publication of The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson in 1967, scientists realized that species diversity on an island was related to two factors: the distance of the island from the mainland and the size of the island. Isolation and small size limited species diversity.

The theory was not limited to islands surrounded by water. It included any area of land separated from similar habitat. Since Yellowstone National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are mountainous, and are both encircled to varying degrees by steppe and human development, they, too, are islands whose species diversity is affected by isolation and size. To emphasize this new reality I often speak of the ecosystem as “Island Yellowstone” or “Yellowstone Island.”

The park’s boundaries were fixed, but the wildness of much of the surrounding land had protected it beyond the mere measure of those boundaries. Greater Yellowstone was tenuously connected by so-called land bridges to similar habitats to the west via the Centennial Range in southern Montana and to the south by the Wind River and Wyoming ranges. The upshot of island biography was that connections to surrounding habitat were as important as places that had been formally protected by legislation as parks, wilderness, and refuges. In particular, mammals in both the park and the ecosystem depended on surrounding public lands and private property for their survival, lands that often lacked long-term protection.

Between 1959 and 1970 Frank and John Craighead studied the behavior, population dynamics, and habitat of Yellowstone’s grizzly population. At that time the park’s grizzly population was declining. Using newly developed radio collars, the Craigheads documented how grizzly bears often wandered or hibernated outside the park’s boundaries. A population adequate for the long-term survival of Yellowstone National Park’s grizzlies would require a much larger protected habitat. Reducing their habitat would lead to their extinction. How large would this protected habitat have to be? Roughly the size of Greater Yellowstone.

In 1987, William Newmark published in the journal Nature his discovery that thirteen of the fourteen national parks he studied had lost some of their mammal species since they were established. Parks such as Yosemite and Mount Rainier had lost more than a quarter of their original species, and smaller parks had lost even more. Newmark predicted that as the national parks and other nature preserves became more isolated, the number of extinctions would increase, and that this increase would be related to both the size of the park and its age—the smaller and older the preserve, the higher the number of extinctions.

Yellowstone is the world’s oldest national park. For nearly a century experts had said it was too small. Some species—such as the wolf—had been exterminated, and many others—the grizzly, fisher, lynx, and wolverine—were threatened and deserved protection. The buffers of undeveloped land—forests and ranch lands that have so far protected it—faced an alarming rate of real estate and energy development. Further isolation of the park would lead to a bleak dialectic, for species loss leads to aggressive human manipulation of natural processes, the very thing the parks were supposed to protect. Preservation and conservation became artificial, human constructs masked as natural systems. Yellowstone National Park would survive, but it would become a cross between a zoo and a prison.

Anyone who thought about this situation realized that the health and integrity of the world’s first national park was at stake. The writer David Quammen entitled an article on the subject “National Parks: Nature’s Dead End.” I prayed he was too pessimistic, but after traveling in the ecosystem for this project these past five years, I began to think he was right.

So if Yellowstone National Park and Greater Yellowstone were islands, how much land around them would have to be protected for them to remain healthy? Everything? No, but we would have to protect corridors between similar habitats to the north and south—north to the Yukon, south to the Colorado Rockies and the Uinta and Wasatch ranges of Utah—and to do so would require a visionary approach to preserving huge parcels of land.

To preserve Yellowstone National Park in a semblance of its current form we would need to preserve Greater Yellowstone, and to preserve Greater Yellowstone would require three things: genuine protection of flora and fauna inside the representative sections of the ecosystem that buffer the national parks, preservation of the current size of the ecosystem from fragmentation or outright destruction, and the reestablishment of corridors to areas by which resident species could maintain contact with their own kind to ensure genetic enrichment. In 2001, Conservation Science, Inc., produced a biological conservation assessment of Greater Yellowstone for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition that was detailed, exhaustive, and persuasive. No one who reads it can deny that Greater Yellowstone is in trouble. We’ve known this, in theory, for decades. Now we know the particulars. And although the fact that species in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks depend on unprotected lands outside the parks may not occur to visitors, it is obvious to anyone who lives, as I do, in Jackson Hole.

Grand Teton’s mountain sheep, whose numbers decreased considerably in the past few decades, often spend most of their year in the adjoining Jedediah Smith Wilderness, where they are hunted and harassed by back-country skiers. The antelope in Grand Teton migrate 200 miles south for the winter through national forests and across Bureau of Land Management lands where habitat protection is minimal or nonexistent, lands that are being plundered by oil and natural gas development. Elk seek winter range on other federal, state, and private lands. Ninety percent of our mule deer winter on private lands, as do 80 percent of trumpeter swans. Sixty-four percent of our native cutthroat trout spawn in waters on private land. Wolves from packs in Yellowstone have colonized Jackson Hole and reached Colorado and Utah. Perhaps most spectacularly: in the summer of 2002 a radio-collared wolverine trapped near where I live in Jackson Hole wandered north to Tower Junction in Yellowstone, then southwest to within miles of Pocatello, Idaho, then across the Salt River and Wyoming ranges, back to Jackson Hole, and south again to the Wind River range, where it threw its collar—all within six weeks. It traveled hundreds of miles through national parks, national forests, BLM land, and private property. Its journey demonstrates better than theory or abstract terminology what will be required to keep Yellowstone healthy and whole.

Tragically or ironically, depending on your philosophical druthers, as our understanding of the importance of Greater Yellowstone grew, forces inimical to its integrity grew, too. Greater Yellowstone has become a battleground that in the years to come will make the conflict over drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge seem like child’s play. It is the one great chance for us to preserve a large, relatively intact ecosystem that is embedded in our history and our hearts. But Greater Yellowstone faces problems—some might call them challenges, but I think they are problems.

First and foremost is the American public’s ignorance of ecology. According to a June 2007 USA Today/Gallup Poll, only 18 percent of Americans believe evolution is “definitely true.” Evolution is the foundation of biology, biology the foundation of ecology, and ecology the basis of informed conservation. How can we expect public support for sound conservation policy against a background of such ignorance?

Second, development continues to fracture Greater Yellowstone at an alarming rate. Roughly a third of Greater Yellowstone is vulnerable to real estate development; perhaps a quarter is vulnerable to industrial energy development. If you believe that an ecosystem can withstand that level of fracturing and disturbance, then you are probably putting your dentures under your pillow for the tooth fairy.

Third, most of the ecosystem is within the state of Wyoming, unfortunately—a state that depends on mineral extraction for its economic welfare because it lacks a personal income tax and a corporate tax, a state that is as reactionary, fundamentalist, and right-wing as any in the nation.

The billion-dollar surplus budgets the state has been enjoying for the past few years are a direct result of energy development. Wyoming produces a third of the coal used in the United States and nearly half the natural gas. At present there are about 63,000 functioning gas and oil wells in the United States. The federal government plans to approve 50,000 new wells in Wyoming alone, most of them in the western and northern parts of the state, either in Greater Yellowstone or its environs. Not to mention the development of wind power, increased coal mining, and new power plants and power lines. Can we do this without irretrievably destroying much of Wyoming? The government, as usual, says, “Trust us.” I trust them about as far as I can spit a brick.

Over the past few years I’ve heard Wyoming referred to as the Saudi Arabia of coal, the Saudi Arabia of natural gas, and the Saudi Arabia of wind power. “We’re gonna have cowboy sheiks!” they exclaim. Well, I reply, go to Saudi Arabia and take a good look. Saudi Arabia is butt-ugly from energy development. Do you want the Yellowstone country to look that way? I don’t.

And I’m not so sure about those cowboy sheiks, either. The energy companies stand accused of bilking the U. S. Treasury out of billions of dollars—that’s our money for developing our resources on our land, and many of those companies are subsidiaries of foreign corporations whose headquarters are in places like Canada and the Barbados.

Fourth, climate change will aggravate the situation. I hope by now everyone realizes that our climate is warming, and that a warming climate will drastically affect all mountain ecosystems. Since it is surrounded by warmer ecosystems, Greater Yellowstone can be imagined as a cool island surrounded by a thermal sea of warmer habitats. As the climate warms, this thermal sea rises, fracturing the island into a chain of even smaller islands and separating them further from the mainland. This will aggravate precisely the two conditions that island biogeography predicts will deplete species diversity: isolation and small size.

Perhaps no one of these problems will be devastating, but common sense suggests that their accumulation will be. It takes only one pernicious event to cascade through an ecosystem, only one falling domino that sets the other dominos in motion, creating change faster than the system can adapt. Ecosystems do collapse, usually, though not always, because of human activity. Could something like that happen to Greater Yellowstone? You bet.

Do we care? Who weeps now for the passenger pigeon, the once-fertile delta where the Colorado River enters the Sea of Cortez, the grizzlies that fed on beached whales along the California coast, or Daniel Boone’s vast Eastern hardwood forest, across which a squirrel could hop, tree to tree, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River? There may come a time when Americans will no longer weep for the loss of Greater Yellowstone, either, but that time is not now. The considerable love, understanding, and legislation that exist can still be harnessed for its protection.

I have watched these changes in Greater Yellowstone for most of my adult life. Given the many problems confronting the ecosystem, I decided to revisit corners of the island that I have known and loved. I also wanted to visit a few places I have never been in order to see what is at stake. I hold the old-fashioned view that to understand how nature works in a particular place you have to spend many years there on the ground and in the water, in all seasons, creating a baseline by which to measure change. Theories, models, and statistics are of limited use; indeed, they are often a place to hide from reality. You have to see things with your own eyes—no one can do it for you. New arrivals and tourists passing through cannot understand what has been lost. As a character in Ernest J. Gaines’s A Gathering of Old Men says, “You had to be here then to be able to don’t see it . . . now. But I was here then, and I don’t see it now.”

I am neither a scientist nor a historian. My intent is neither comprehensive coverage nor definitive detail. What I sought in these travels was much more personal, my own reckoning of how this place where I’ve lived most of my life is doing, whether its soul is indeed intact, as authorities and experts would have it, or unraveling. I wanted to walk and drive, float rivers, paddle lakes, fish, study trees and critters, filter past memories through present events, and write a bit about what I saw and felt. It is this modest project that has been recorded here.

Copyright © 2008 by Jack Turner. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 9780312560959

ISBN-10: 0312560958

Published: 12th May 2009

Format: Paperback

Language: English

Number of Pages: 298

Audience: General Adult

Publisher: St. Martins Press-3PL

Country of Publication: US

Dimensions (cm): 21.59 x 13.97 x 1.7

Weight (kg): 0.39

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.

You Can Find This Book In

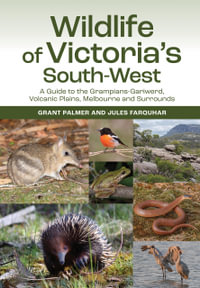

Wildlife of Victoria's South-West

A Guide to the Grampians-Gariwerd, Volcanic Plains, Melbourne and Surrounds

Paperback

RRP $49.99

$32.90

OFF