At a Glance

320 Pages

14 - 17

9 - 12

21.44 x 16.05 x 2.95

Hardcover

$36.80

or 4 interest-free payments of $9.20 with

orAims to ship in 10 to 15 business days

- He has recurring dreams about a strange white cat.

- He can't quite remember past memories, but he's beginning to suspect his brothers are up to no good.

- He killed his best friend (his love), Lila, when he was 14.

Cassel has carefully built up a façade of normalcy, blending into the crowd. But his façade starts to crumble when he finds himself sleepwalking, propelled into the night by terrifying dreams about a white cat that wants to tell him something. He’s noticing other disturbing things too, including the strange behavior of his two brothers. They are keeping secrets from him. As Cassel begins to suspect he’s part of a huge con game, he must unravel his past and his memories. To find out the truth, Cassel will have to outcon the conmen.

Holly Black has created a gripping tale of mobsters and dark magic where a single touch can bring love -- or death -- and your dreams might be more real than your memories.

Industry Reviews

I wake up barefoot, standing on cold slate tiles. Looking dizzily down. I suck in a breath of icy air.

Above me are stars. Below me, the bronze statue of Colonel Wallingford makes me realize I'm seeing the quad from the peak of Smythe Hall, my dorm.

I have no memory of climbing the stairs up to the roof. I don't even know how to get where I am, which is a problem since I'm going to have to get down, ideally in a way that doesn't involve dying.

Teetering, I will myself to be as still as possible. Not to inhale too sharply. To grip the slate with my toes.

The night is quiet, the kind of hushed middle-of-the-night quiet that makes every shuffle or nervous panting breath echo. When the black outlines of trees overhead rustle, I jerk in surprise. My foot slides on something slick. Moss.

I try to steady myself, but my legs go out from under me.

I scrabble for something to hold on to as my bare chest slams down on the slate. My palm comes down hard on a sharp bit of copper flashing, but I hardly feel the pain. Kicking out, my foot finds a snow guard, and I press my toes against it, steadying myself. I laugh with relief, even though I am shaking so badly that climbing is out of the question.

Cold makes my fingers numb. The adrenaline rush makes my brain sing.

"Help," I say softly, and feel crazy nervous laughter bubble up my throat. I bite the inside of my cheek to tamp it down.

I can't ask for help. I can't call anyone. If I do, then my carefully maintained pretense that I'm just a regular guy is going to fade forever. Sleepwalking is kid's stuff, weird and embarrassing.

Looking across the roof in the dim light, I try to make out the pattern of snow guards, tiny triangular pieces of clear plastic that keep ice from falling in a sheet, tiny triangular pieces that were never meant to hold my weight. If I can get closer to a window, maybe I can climb down.

I edge my foot out, shifting as slowly as I can and worming toward the nearest snow guard. My stomach scrapes against the slate, some of the tiles chipped and uneven beneath me. I step onto the first guard, then down to another and across to one at the edge of the roof. There, panting, with the windows too far beneath me and with nowhere left to go, I decide I am not willing to die from embarrassment.

I suck in three deep breaths of cold air and yell.

"Hey! Hey! Help!" The night absorbs my voice. I hear the distant swell of engines along the highway, but nothing from the windows below me.

"HEY!" I scream it this time, guttural, as loudly as I can, loud enough that the words scrape my throat raw. "Help!"

A light flickers on in one of the rooms and I see the press of palms against a glass pane. A moment later the window slides open. "Hello?" someone calls sleepily from below. For a moment her voice reminds me of another girl. A dead girl.

I hang my head off the side and try to give my most chagrined smile. Like she shouldn't freak out. "Up here," I say. "On the roof."

"Oh, my God," Justine Moore gasps.

Willow Davis comes to the window. "I'm getting the hall master."

I press my cheek against the cold tile and try to convince myself that everything's okay, that it's not a curse, that if I just hang on a little longer, things are going to be fine.

A crowd gathers below me, spilling out of the dorms.

"Jump," some jerk shouts. "Do it!"

"Mr. Sharpe?" Dean Wharton calls. "Come down from there at once, Mr. Sharpe!" His silver hair sticks up like he's been electrocuted, and his robe is inside out and badly tied. The whole school can see his tighty-whities.

I realize abruptly that I'm wearing only boxers. If he looks ridiculous, I look worse.

"Cassel!" Ms. Noyes yells. "Cassel, don't jump! I know things have been hard..." She stops there, like she isn't quite sure what to say next. She's probably trying to remember what's so hard. I have good grades. Play well with others.

I look down again. Camera phones flash. Freshmen hang out of windows next door in Strong House, and juniors and seniors stand around on the grass in their pajamas and nightgowns, even though teachers are desperately trying to herd them back inside.

I give my best grin. "Cheese," I say softly.

"Get down, Mr. Sharpe," yells Dean Wharton. "I'm warning you!"

"I'm okay, Ms. Noyes," I call. "I don't know how I got up here. I think I was sleepwalking."

I'd dreamed of a white cat. It leaned over me, inhaling sharply, as if it was going to suck the breath from my lungs, but then it bit out my tongue instead. There was no pain, only a sense of overwhelming, suffocating panic. In the dream my tongue was a wriggling red thing, mouse-size and wet, that the cat carried in her mouth. I wanted it back. I sprang up out of the bed and grabbed for her, but she was too lean and too quick. I chased her. The next thing I knew, I was teetering on a slate roof.

A siren wails in the distance, drawing closer. My cheeks hurt from smiling.

Eventually a fireman climbs a ladder to get me down. They put a blanket around me, but by then my teeth are chattering so hard that I can't answer any of their questions. It's like the cat bit out my tongue after all.

The last time I was in the headmistress's office, my grandfather was there with me to enroll me at the school. I remember watching him empty a crystal dish of peppermints into the pocket of his coat while Dean Wharton talked about what a fine young man I would be turned into. The crystal dish went into the opposite pocket.

Wrapped in a blanket, I sit in the same green leather chair and pick at the gauze covering my palm. A fine young man indeed.

"Sleepwalking?" Dean Wharton says. He's dressed in a brown tweed suit, but his hair is still wild. He stands near a shelf of outdated encyclopedias and strokes a gloved finger over their crumbling leather spines.

I notice there's a new cheap glass dish of mints on the desk. My head is pounding. I wish the mints were aspirin.

"I used to sleepwalk," I say. "I haven't done it in a long time."

Somnambulism isn't all that uncommon in kids, boys especially. I looked it up online after waking in the driveway when I was thirteen, my lips blue with cold, unable to shake the eerie feeling that I'd just returned from somewhere I couldn't quite recall.

Outside the leaded glass windows the rising sun limns the trees with gold. The headmistress, Ms. Northcutt, looks puffy and red-eyed. She's drinking coffee out of a mug with the Wallingford logo on it and gripping it so tightly the leather of her gloves over her knuckles is pulled taut.

"I heard you've been having some problems with your girlfriend," Headmistress Northcutt says.

"No," I say. "Not at all." Audrey broke up with me after the winter holiday, exhausted by my moodiness. It's impossible to have problems with a girlfriend who's no longer mine.

The headmistress clears her throat. "Some students think you are running a betting pool. Are you in some kind of trouble? Owe someone money?"

I look down and try not to smile at the mention of my tiny criminal empire. It's just a little forgery and some bookmaking. I'm not running a single con; I haven't even taken up my brother Philip's suggestion that we could be the school's main supplier for underage booze. I'm pretty sure the headmistress doesn't care about betting, but I'm glad she doesn't know that the most popular odds are on which teachers are hooking up. Northcutt and Wharton are a long shot, but that doesn't stop people laying cash on them. I shake my head.

"Have you experienced mood swings lately?" Dean Wharton asks.

"No," I say.

"What about changes in appetite or sleep patterns?" He sounds like he's reciting the words from a book.

"The problem is my sleep patterns," I say.

"What do you mean?" asks Headmistress Northcutt, suddenly intent.

"Nothing! Just that I was sleepwalking, not trying to kill myself. And if I wanted to kill myself, I wouldn't throw myself off a roof. And if I was going to throw myself off a roof, I would put on some pants before I did it."

The headmistress takes a sip from her cup. She's relaxed her grip. "Our lawyer advised me that until a doctor can assure us that nothing like this will happen again, we can't allow you to stay in the dorms. You're too much of an insurance liability."

I thought that people would give me a lot of crap, but I never thought there would be any real consequences. I thought I was going to get a scolding. Maybe even a couple of demerits. I'm too stunned to say anything for a long moment. "But I didn't do anything wrong."

Which is stupid, of course. Things don't happen to people because they deserve them. Besides, I've done plenty wrong.

"Your brother Philip is coming to pick you up," Dean Wharton says. He and the headmistress exchange looks, and Wharton's hand goes unconsciously to his neck, where I see the colored cord and the outline of the amulet under his white shirt.

I get it. They're wondering if I've been worked. Cursed. It's not that big a secret that my grandfather was a death worker for the Zacharov family. He's got the blackened stubs where his fingers used to be to prove it. And if they read the paper, they know about my mother. It's not a big leap for Wharton and Northcutt to blame any and all strangeness concerning me on curse work.

"You can't kick me out for sleepwalking," I say, getting to my feet. "That can't be legal. Some kind of discrimination against -- " I stop speaking as cold dread settles in my stomach, because for a moment I wonder if I could have been cursed. I try to think back to whether someone brushed me with a hand, but I can't recall anyone touching me who wasn't clearly gloved.

"We haven't come to any determination about your future here at Wallingford yet." The headmistress leafs through some of the papers on her desk. The dean pours himself a coffee.

"I can still be a day student." I don't want to sleep in an empty house or crash with either of my brothers, but I will. I'll do whatever lets me keep my life the way it is.

"Go to your dorm and pack some things. Consider yourself on medical leave."

"Just until I get a doctor's note," I say.

Neither of them replies, and after a few moments of standing awkwardly, I head for the door.

Don't be too sympathetic. Here's the essential truth about me: I killed a girl when I was fourteen. Her name was Lila, she was my best friend, and I loved her. I killed her anyway. There's a lot of the murder that seems like a blur, but my brothers found me standing over her body with blood on my hands and a weird smile tugging at my mouth. What I remember most is the feeling I had looking down at Lila -- the giddy glee of having gotten away with something.

No one knows I'm a murderer except my family. And me, of course.

I don't want to be that person, so I spend most of my time at school faking and lying. It takes a lot of effort to pretend you're something you're not. I don't think about what music I like; I think about what music I should like. When I had a girlfriend, I tried to convince her I was the guy she wanted me to be. When I'm in a crowd, I hang back until I can figure out how to make them laugh. Luckily, if there's one thing I'm good at, it's faking and lying.

I told you I'd done plenty wrong.

I pad, still barefoot, still wrapped in the scratchy fireman's blanket, across the sunlit quad and up to my dorm room. Sam Yu, my roommate, is looping a skinny tie around the collar of a wrinkled dress shirt when I walk through the door. He looks up, startled.

"I'm fine," I say wearily. "In case you were going to ask."

Sam's a horror film enthusiast and hard-core science geek who has covered our dorm room with bug-eyed alien masks and gore-spattered posters. His parents want him to go to MIT and from there to some profitable pharmaceuticals gig. He wants to do special effects for movies. Despite the facts that he's built like a bear and is obsessed with fake blood, he has so far failed to stand up to them to the degree that they don't even know there's a disagreement. I like to think we're sort of friends.

We don't hang out with many of the same people, which makes being sort of friends easier.

"I wasn't doing...whatever you think I was doing," I tell him. "I don't want to die or anything."

Sam smiles and pulls on his Wallingford gloves. "I was just going to say that it's a good thing you don't sleep commando."

I snort and drop onto my cot. The frame squeaks in protest. On the pillow next to my head rests a new envelope, marked with a code telling me a freshman wants to put fifty dollars on Victoria Quaroni to win the talent show. The odds are astronomical, but the money reminds me that someone's going to have to keep the books and pay out while I'm away.

Sam kicks the base of the footboard lightly. "You sure you're okay?"

I nod. I know I should tell him that I'm going home, that he's about to become one of those lucky guys with a single, but I don't want to disturb my own fragile sense of normalcy. "Just tired."

Sam picks up his backpack. "See you in class, crazyman."

I raise my bandaged hand in farewell, then stop myself. "Hey, wait a sec."

Hand on the doorknob, he turns.

"I was just thinking...if I'm gone. Do you think you could let people keep dropping off the money here?" It bothers me to ask, simultaneously putting me in his debt and making the whole kicked-out thing real, but I'm not ready to give up the one thing I've got going for me at Wallingford.

He hesitates.

"Forget it," I say. "Pretend I never -- "

He interrupts me. "Do I get a percentage?"

"Twenty-five," I say. "Twenty-five percent. But you're going to have to do more than just collect the money for that."

He nods slowly. "Yeah, okay."

I grin. "You're the most trustworthy guy I know."

"Flattery will get you everywhere," Sam says. "Except, apparently, off a roof."

"Nice," I say with a groan. I push myself off the bed and take a clean pair of itchy black uniform pants out of the dresser.

"So why would you be gone? They're not kicking you out, right?"

Pulling on the pants, I turn my face away, but I can't keep the unease out of my voice. "No. I don't know. Let me set you up."

He nods. "Okay. What do I do?"

"I'll give you my notebook on point spreads, tallies, everything, and you just fill in whatever bets you get." I stand, pulling my desk chair over to the closet and hopping up on the seat. "Here." My fingers close on the notebook I taped above the door. I rip it down. Another one from sophomore year is still up there, from when business got big enough I could no longer rely on my pretty-good-but-not-photographic memory.

Sam half-smiles. I can tell he's amazed that he never noticed my hiding spot. "I think I can manage that."

The pages he's flipping through are records of all the bets made since the beginning of our junior year at Wallingford, and the odds on each. Bets on whether the mouse loose in Stanton Hall will be killed by Kevin Brown with his mallet, or by Dr. Milton with his bacon-baited traps, or be caught by Chaiyawat Terweil with his lettuce-filled and totally humane trap. (The odds favor the mallet.) On whether Amanda, Sharone, or Courtney would be cast as the female lead in Pippin and whether the lead would be taken down by her understudy. (Courtney got it; they're still in rehearsals.) On how many times a week "nut brownies with no nuts" will be served in the cafeteria.

Real bookies take a percentage, relying on a balanced book to guarantee a profit. Like, if someone puts down five bucks on a fight, they're really putting down four fifty, and the other fifty cents is going to the bookie. The bookie doesn't care who wins; he only cares that the odds work so he can use the money from the losers to pay the winners. I'm not a real bookie. Kids at Wallingford want to bet on silly stuff, stuff that might never come true. They have money to burn. So some of the time I calculate the odds the right way -- the real bookie way -- and some of the time I calculate the odds my way and just hope I get to pocket everything instead of paying out what I can't afford. You could say that I'm gambling too. You'd be right.

"Remember," I say, "cash only. No credit cards; no watches."

He rolls his eyes. "Are you seriously telling me someone thinks you have a credit card machine up in here?"

"No," I say. "They want you to take their card and buy something that costs what they owe. Don't do it; it looks like you stole their card, and believe me, that's what they'll tell their parents."

Sam hesitates. "Yeah," he says finally.

"Okay," I say. "There's a new envelope on the desk. Don't forget to mark down everything." I know I'm nagging, but I can't tell him that I need the money I make. It's not easy to go to a school like this without money. I'm the only seventeen-year-old at Wallingford without a car.

I motion to him to hand me the book.

Just as I'm taping it into place, someone raps loudly on the door, causing me to nearly topple over. Before I can say anything, it opens, and our hall master walks in. He looks at me like he's half-expecting to find me threading a noose.

I hop down from the chair. "I was just -- "

"Thanks for getting down my bag," Sam says.

"Samuel Yu," says Mr. Valerio. "I'm fairly sure that breakfast is over and classes have started."

"I bet you're right," Sam says, with a smirk in my direction.

I could con Sam if I wanted to. I'd do it just this way, asking for his help, offering him a little profit at the same time. Take him for a chunk of his parents' cash. I could con Sam, but I won't.

Really, I won't.

As the door clicks shut behind Sam, Valerio turns to me. "Your brother can't come until tomorrow morning, so you're going to have to attend classes with the rest of the students. We're still discussing where you'll be spending the night."

"You can always tie me to the bedposts," I say, but Valerio doesn't find that very funny.

My mother explained the basics of the con around the same time she explained about curse work. For her the curse was how she got what she wanted and the con was how she got away with it. I can't make people love or hate instantly, like she can, turn their bodies against them like Philip can, or take their luck away like my other brother, Barron, but you don't need to be a worker to be a con artist.

For me the curse is a crutch, but the con is everything.

It was my mother who taught me that if you're going to screw someone over -- with magic and wit, or wit alone -- you have to know the mark better than he knows himself.

The first thing you have to do is gain his confidence. Charm him. Just be sure he thinks he's smarter than you are. Then you -- or, ideally, your partner -- suggest the score.

Let your mark get something right up front the first time. In the business that's called the "convincer." When he knows he's already got money in his pocket and can walk away, that's when he relaxes his guard.

The second go is when you introduce bigger stakes. The big score. This is the part my mother never has to worry about. As an emotion worker, she can make anyone trust her. But she still needs to go through the steps, so that later, when they think back on it, they don't figure out she worked them.

After that there's only the blow-off and the getaway.

Being a con artist means thinking that you're smarter than everyone else and that you've thought of everything. That you can get away with anything. That you can con anyone.

I wish I could say that I don't think about the con when I deal with people, but the difference between me and my mother is that I don't con myself.

Chapter Two

I only have enough time to pull on my uniform and run to French class; breakfast is long over. Wallingford television crackles to life as I dump my books onto my desk. Sadie Flores announces from the screen that during activities period the Latin club will be having a bake sale to support their building a small outdoor grotto, and that the rugby team will meet inside the gymnasium. I manage to stumble through my classes until I actually fall asleep during history. I wake abruptly with drool wetting the sleeve of my shirt and Mr. Lewis asking, "What year was the ban put into effect, Mr. Sharpe?"

"Nineteen twenty-nine," I mumble. "Nine years after Prohibition started. Right before the stock market crashed."

"Very good," he says unhappily. "And can you tell me why the ban hasn't been repealed like prohibition?"

I wipe my mouth. My headache hasn't gotten any better. "Uh, because the black market supplies people with curse work anyway?"

A couple of people laugh, but Mr. Lewis isn't one of them. He points toward the board, where a jumble of chalk reasons are written. Something about economic initiatives and a trade agreement with the European Union. "Apparently you can do lots of things very skillfully while asleep, Mr. Sharpe, but attending my class does not seem to be one of them."

He gets the bigger laugh. I stay awake for the rest of the period, although several times I have to jab myself with a pen to do it.

I go back to my dorm and sleep through the period when I should be getting help from teachers in classes where I'm struggling, through track practice, and through the debate team meeting. Waking up halfway through dinner, I feel the rhythm of my normal life receding, and I have no idea how to get it back.

Wallingford Preparatory is a lot like how I pictured it when my brother Barron brought home the brochure. The lawns are less green and the buildings are smaller, but the library is impressive enough and everyone wears jackets to dinner. Kids come to Wallingford for two very different reasons. Either private school is their ticket to a fancy university, or they got kicked out of public school and are using their parents' money to avoid the school for juvenile delinquents that's their only other option.

Wallingford isn't exactly Choate or Deerfield Academy, but it was willing to take me, even with my ties to the Zacharovs. Barron thought the school would give me structure. No messy house. No chaos. I've done well too. Here, my inability to do curse work is actually an advantage -- the first time that it's been good for anything. And yet I see in myself a disturbing tendency to seek out all the trouble this new life should be missing. Like running the betting pool when I need money. I can't seem to stop working the angles.

The dining hall is wood-paneled with a high, arched ceiling that makes our noise echo. The walls are hung with paintings of important heads-of-school and, of course, Wallingford himself. Colonel Wallingford, the founder of Wallingford Preparatory, killed by curse work a year before the ban went into effect, sneers down at me from his gold frame.

My shoes clack on the worn marble tiles, and I frown as the voices around me merge into a single buzzing that rings in my ears. Walking through to the kitchen, my hands feel damp, sweat soaking the cotton of my gloves as I push open the door.

I look around automatically to see if Audrey's here. She's not, but I shouldn't have looked. I've got to ignore her just enough that she doesn't think I care, but not too much. Too much will give me away as well.

Especially today, when I'm so disoriented.

"You're late," one of the food service ladies says without looking up from wiping the counter. She looks past retirement age -- at least as old as my grandfather -- and a few of her permed curls have tumbled out the side of her plastic cap. "Dinner's over."

"Yeah." And then I mumble, "Sorry."

"The food's put away." She looks up at me. She holds up her plastic-covered hands. "It's going to be cold."

"I like cold food." I give her my best sheepish half smile.

She shakes her head. "I like boys with a good appetite. All of you look so skinny, and in the magazines they talk about you starving yourselves like girls."

"Not me," I say, and my stomach growls, which makes her laugh.

"Go outside and I'll bring you a plate. Take a few cookies off the tray here too." Now that she's decided I'm a poor child in need of feeding, she seems happy to fuss.

Unlike in most school cafeterias, the food at Wallingford is good. The cookies are dark with molasses and spicy with ginger. The spaghetti, when she brings it, is lukewarm, but I can taste chorizo in the red sauce. As I sop up some of it with bread, Daneca Wasserman comes over to the table.

"Can I sit down?" she asks.

I glance up at the clock. "Study hall's going to start soon." Her tangle of brown curls looks unbrushed, pulled back with a sandalwood headband. I drop my gaze to the hemp bag at her hip, studded with buttons that read powered by tofu, down on prop 2, and worker rights.

"You weren't at debate club," she says.

"Yeah." I feel bad about avoiding Daneca or giving her rude half answers, but I've been doing it since I started at Wallingford. Even though she's one of Sam's friends and living with him makes avoiding Daneca more difficult.

"My mother wants to talk with you. She says that what you did was a cry for help."

"It was," I say. "That's why I was yelling 'Heeeelp!' I don't really go in for subtlety."

She makes an impatient noise. Daneca's family are cofounders of HEX, the advocacy group that wants to make working legal again -- basically so laws against more serious works can be better enforced. I've seen her mother on television, filmed sitting in the office of her brick house in Princeton, a blooming garden visible through the window behind her. Mrs. Wasserman talked about how, despite the laws, no one wanted to be without a luck worker at a wedding or a baptism, and that those kinds of works were beneficial. She talked about how it benefited crime families to prevent workers from finding ways to use their talents legally. She admitted to being a worker herself. It was an impressive speech. A dangerous speech.

"Mom deals with worker families all the time," Daneca says. "The issues worker kids face."

"I know that, Daneca. Look, I didn't want to join your junior HEX club last year, and I don't want to mess with that kind of stuff now. I'm not a worker, and I don't care if you are. Find someone else to recruit or save or whatever it is you are trying to do. And I don't want to meet your mother."

She hesitates. "I'm not a worker. I'm not. Just because I want to -- "

"Whatever. I said I don't care."

"You don't care that workers are being rounded up and shot in South Korea? And here in the U.S. they're being forced into what's basically indentured servitude for crime families? You don't care about any of it?"

"No, I don't care."

Across the hall Valerio is headed toward me. That's enough to make Daneca decide she doesn't want to risk a demerit for not being where she's supposed to be. Hand on her bag, she walks off with a single glance back at me. The combination of disappointment and contempt in that last look hurts.

I put a big chunk of sauce-soaked bread in my mouth and stand.

"Congratulations. You're going to be sleeping in your room tonight, Mr. Sharpe."

I nod, chewing. Maybe if I make it through tonight, they'll consider letting me stay.

"But I want you to know that I have Dean Wharton's dog and she's going to be sleeping in the hallway. That dog is going to bark like hell if you go on one of your midnight strolls. I better not see you out of your room, not even to go to the bathroom. Do you understand?"

I swallow. "Yes, sir."

"Better get back and start on your homework."

"Right," I say. "Absolutely. Thank you, sir."

I seldom walk back from the dining hall alone. Above the trees, their leaves the pale green of new buds, bats weave through the still-bright sky. The air is heavy with the smell of crushed grass, threaded through with smoke. Somewhere someone's burning the wet, half-decomposed foliage of winter.

Sam sits at his desk, earbuds in, huge back to the door and head down as he doodles in the pages of his physics textbook. He barely looks up when I flop down on the bed. We have about three hours of homework a night, and our evening study period is only two hours, so if you want to spend the break at half-past-nine not freaking out, you have to cram. I'm not sure that the picture of the wide-eyed zombie girl biting out the brains of senior douchebag James Page is part of Sam's homework, but if it is, his physics teacher is awesome.

I pull out books from my backpack and start on trig problems, but as my pencil scrapes across the page of my notebook, I realize I don't really remember class well enough to solve anything. Pushing those books toward my pillow, I decide to read the chapter we were assigned in mythology. It's some more messed-up Olympian family stuff, starring Zeus. His pregnant girlfriend, Semele, gets tricked by his wife, Hera, into demanding to see Zeus in all his godly glory. Despite knowing this is going to kill Semele, he shows her the goods. A few minutes later he's cutting baby Dionysus out of burned-up Semele's womb and sewing him into his own leg. No wonder Dionysus drank all the time. I just get to the part where Dionysus is being raised as a girl (to keep him hidden from Hera, of course), when Kyle bangs against the door frame.

"What?" Sam says, pulling off one of his buds and turning in his chair.

"Phone for you," Kyle says, looking in my direction.

I guess before everyone had a cell phone, the only way students could call home was to save up their quarters and feed them into the ancient pay phone at the end of every dorm hall. Despite the occasional midnight crank call, Wallingford has left those old phones where they were. People occasionally still use them; mostly parents calling someone whose cell battery died or who wasn't returning messages. Or my mother, calling from jail.

I pick up the familiar heavy black receiver. "Hello?"

"I am very disappointed in you," Mom says. "That school is making you soft in the head. What were you doing up on a roof?" Theoretically Mom shouldn't be able to call a pay phone from prison, but she found a way around that. First she gets my sister-in-law to accept the charges, then Maura can three-way call anyone Mom needs. Lawyers. Philip. Barron. Me.

Of course, Mom could three-way call my cell phone, but she's sure that all cell phone conversations are being listened to by some shady peeping-Tom branch of the government, so she tries to avoid using them.

"I'm okay," I say. "Thanks for checking in on me." Her voice reminds me that Philip's coming to pick me up in the morning. I have a brief fantasy of him never bothering to show up and the whole thing blowing over.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Holly Black.

ISBN: 9781416963967

ISBN-10: 1416963960

Series: Curse Workers

Published: 1st May 2010

Format: Hardcover

Language: English

Number of Pages: 320

Audience: Teenager/Young Adult

For Ages: 14 - 17 years old

For Grades: 9 - 12

Publisher: MARGARET K MCELDERRY BOOKS

Country of Publication: US

Dimensions (cm): 21.44 x 16.05 x 2.95

Weight (kg): 0.4

Shipping

| Standard Shipping | Express Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Metro postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Regional postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

| Rural postcodes: | $9.99 | $14.95 |

How to return your order

At Booktopia, we offer hassle-free returns in accordance with our returns policy. If you wish to return an item, please get in touch with Booktopia Customer Care.

Additional postage charges may be applicable.

Defective items

If there is a problem with any of the items received for your order then the Booktopia Customer Care team is ready to assist you.

For more info please visit our Help Centre.

You Can Find This Book In

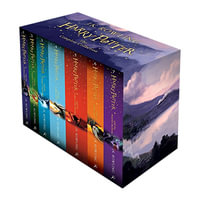

Christmas at Hogwarts

A joyfully illustrated gift book featuring text from 'Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone'

Hardcover

RRP $29.99

$22.25

OFF

An Illustrated Treasury of Grimm's Fairy Tales

Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Hansel and Gretel and Many More Classic Stories

Hardcover

RRP $46.99

$39.90

OFF

This product is categorised by

- Kids & Children's BooksChildren, Teenagers & Young Adults (YA) FictionScience Fiction for Children & Teenagers

- Kids & Children's BooksChildren, Teenagers & Young Adults (YA) FictionFamily & Home Stories for Children & Teenagers

- Kids & Children's BooksPersonal & Social IssuesHandling Family Issues for Children & TeenagersDealing with Siblings for Children & Teenagers

- Kids & Children's BooksChildren, Teenagers & Young Adults (YA) FictionTraditional Stories for Children